When a bone breaks, the pain can be sudden, sharp, and overwhelming. Unlike a bruise or muscle strain, fracture pain often feels deep, unrelenting, and difficult to ignore. But what exactly causes this intense sensation? Understanding the science behind fracture pain reveals a complex interplay of biological responses—nervous system activation, tissue damage, inflammation, and psychological factors—all converging to create one of the most acute forms of physical discomfort.

Bone fractures are among the most common traumatic injuries, affecting millions annually. Whether from a fall, sports accident, or underlying condition like osteoporosis, the experience of pain is nearly universal. Yet many people don’t realize that bones themselves contain nerves, or that the body’s response to injury extends far beyond the break site. This article explores the physiology of fracture pain, identifies key contributing factors, and offers practical insights into managing discomfort during recovery.

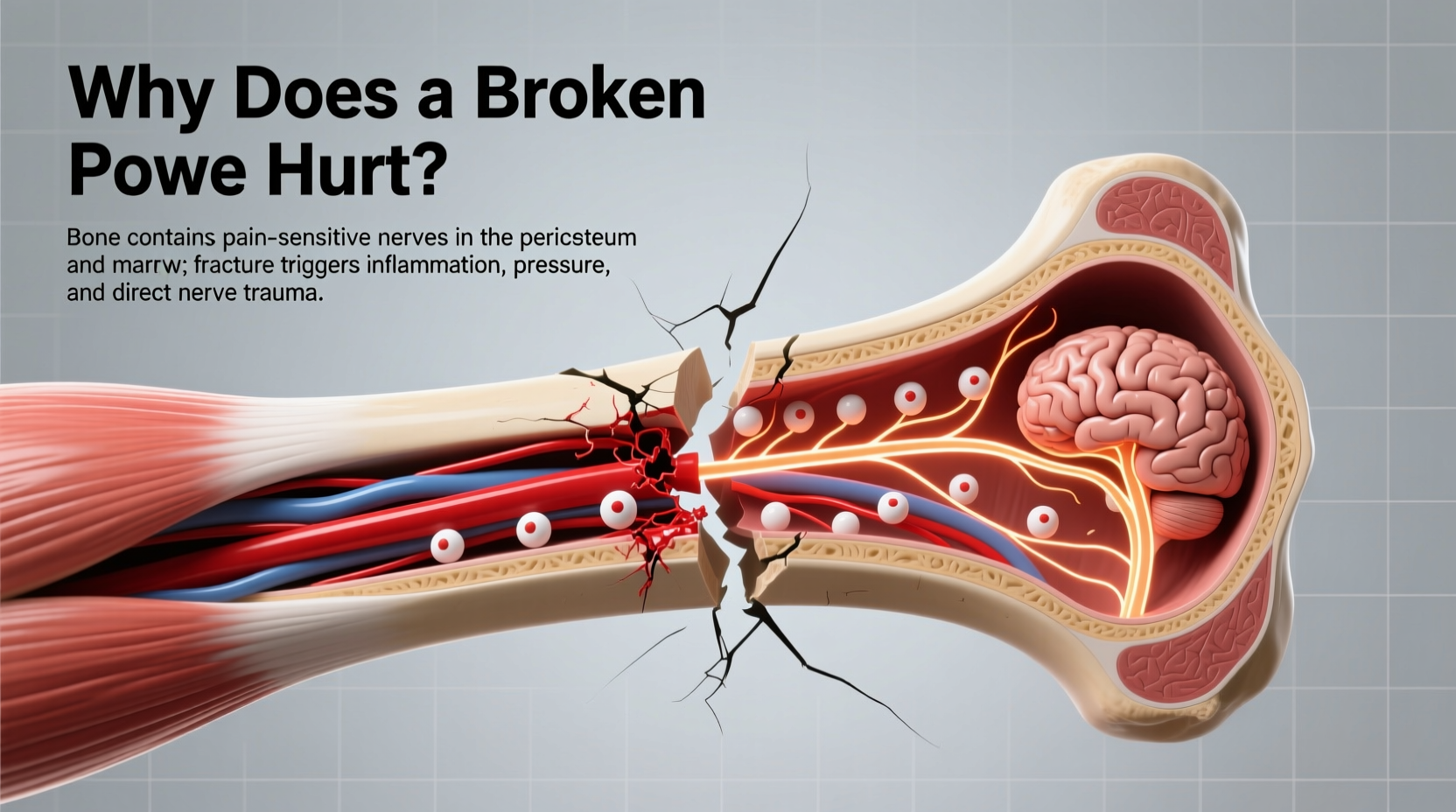

The Anatomy of Bone and Pain Perception

Bones are not inert structures—they are living tissues rich in blood vessels, cells, and sensory nerves. The outer layer, called the periosteum, is particularly dense with nerve endings. When a fracture occurs, it's often the tearing or irritation of the periosteum that triggers immediate, severe pain. This membrane plays a crucial role in bone growth and repair, but its high innervation makes it extremely sensitive to mechanical stress and chemical changes.

Inside the bone, the marrow also contributes to pain signaling. Marrow contains connective tissues and immune cells that respond rapidly to trauma. As blood vessels rupture and internal pressure increases, nociceptors—specialized pain receptors—activate and send distress signals through peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and brain.

The central nervous system interprets these signals as pain, but the intensity isn’t solely dependent on the size of the break. A hairline fracture in a weight-bearing bone like the tibia may cause more discomfort than a clean break in a smaller, less-used bone due to ongoing pressure and movement.

Biological Mechanisms Behind Fracture Pain

Fracture pain arises from multiple overlapping processes:

- Mechanical disruption: The physical separation of bone ends damages surrounding tissues, including muscles, ligaments, and blood vessels.

- Inflammatory response: Within minutes of injury, the body releases inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, and cytokines. These chemicals sensitize nearby nerve endings, amplifying pain signals—a phenomenon known as peripheral sensitization.

- Edema and pressure: Swelling around the fracture site increases pressure on nerves and soft tissues, contributing to throbbing or constant pain.

- Ischemia: Reduced blood flow due to damaged vessels can lead to localized oxygen deprivation, further irritating nerve cells.

Over time, if pain persists beyond the initial phase, central sensitization may occur. This neurological adaptation means the spinal cord and brain become hyper-responsive to pain signals, potentially leading to chronic discomfort even after healing begins.

“Acute fracture pain is primarily driven by tissue destruction and inflammation, but untreated or poorly managed pain can rewire neural pathways,” says Dr. Lena Patel, a pain management specialist at Boston Spine Institute. “Early intervention is critical to prevent long-term complications.”

Stages of Fracture Pain: From Injury to Healing

Pain evolves throughout the recovery process. Recognizing these phases helps patients and caregivers anticipate needs and adjust treatment accordingly.

- Immediate (0–72 hours): Sharp, localized pain dominates. Movement intensifies discomfort. Swelling and bruising develop quickly.

- Subacute (3 days–2 weeks): Inflammation peaks. Pain may shift from sharp to dull or throbbing. Nerve sensitivity remains high.

- Repair phase (2–6 weeks): New bone tissue forms (callus). Pain typically decreases but may flare with activity or improper alignment.

- Remodeling (6 weeks–months): Bone strengthens and reshapes. Most pain resolves, though some report intermittent aches, especially in cold or damp weather.

Individual variation is significant. Age, overall health, fracture location, and mental state all influence pain perception. Older adults may feel less acute pain initially due to reduced nerve sensitivity, but they face higher risks of delayed healing and secondary complications.

Common Misconceptions About Fracture Pain

Several myths persist about broken bones and pain:

| Misconception | Reality |

|---|---|

| If you can move the limb, the bone isn’t broken. | Some fractures allow limited motion. Movement worsens damage and increases pain. |

| No pain means no fracture. | Numbness from nerve injury or shock can mask pain. Imaging is required for diagnosis. |

| Casting eliminates pain immediately. | Casts stabilize the area but don’t stop inflammation. Pain relief requires medication and rest. |

| Pain should disappear once the cast comes off. | Residual stiffness, weakness, and nerve hypersensitivity can linger for weeks. |

Managing Fracture Pain: A Practical Checklist

Effective pain control supports healing and improves quality of life during recovery. Follow this checklist to stay on track:

- ✔️ Use prescribed pain medications as directed—do not wait until pain becomes severe.

- ✔️ Apply ice packs (15–20 minutes every 2–3 hours) during the first 48 hours to reduce swelling.

- ✔️ Elevate the injured limb above heart level when possible to minimize edema.

- ✔️ Avoid putting weight on the fracture unless cleared by a physician.

- ✔️ Attend follow-up appointments to monitor healing progress and adjust treatment.

- ✔️ Practice gentle breathing or mindfulness techniques to manage pain-related anxiety.

Real Example: Recovery After a Wrist Fracture

Samantha, a 34-year-old graphic designer, fell on an outstretched hand while hiking. She heard a snap and felt instant, searing pain in her wrist. Though she could wiggle her fingers, the base of her thumb swelled rapidly. At the ER, X-rays confirmed a distal radius fracture.

Initially, she was given ibuprofen and a splint. Despite the medication, her pain spiked at night. Her doctor explained that inflammation was pressing on nerves near the break. She started using scheduled acetaminophen with low-dose opioids for the first five days, combined with elevation and ice. By day 10, pain had decreased to a manageable level. Over the next six weeks, she transitioned to physical therapy. Even after cast removal, she experienced occasional twinges when typing—likely due to residual nerve sensitivity. With ergonomic adjustments and strengthening exercises, her symptoms resolved within three months.

Samantha’s case illustrates how timely care, proper pain management, and patience are essential components of recovery—even when the fracture itself heals well.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a broken bone hurt even if you don’t feel it right away?

Yes. Adrenaline, shock, or concurrent injuries can temporarily suppress pain. Some fractures, especially stress fractures, develop gradually and may only cause mild discomfort initially.

Why does my broken bone ache more at night?

Nighttime pain is common due to reduced distractions, increased awareness of bodily sensations, and lying still—which can allow fluid to pool and increase pressure around the injury.

Will I always feel pain in the fractured area after healing?

Most people fully recover without lasting pain. However, some experience weather-sensitive aches or occasional discomfort, especially if arthritis develops later in the joint near the healed fracture.

Conclusion: Taking Control of Fracture Pain

Fracture pain is not just a symptom—it’s a vital signal from your body demanding attention and care. Understanding its origins empowers you to respond effectively, seek appropriate treatment, and participate actively in your recovery. While pain cannot always be eliminated entirely, combining medical guidance with self-management strategies significantly improves outcomes.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?