After a night of drinking, many people wake up with a dry mouth, headache, and fatigue—classic signs of dehydration. But what exactly happens inside your body when you consume alcohol that leads to this state? While it's common knowledge that alcohol causes dehydration, few understand the physiological mechanisms behind it. This article breaks down the science of how alcohol disrupts your body’s fluid balance, affects hormone regulation, and impairs kidney function. You'll also learn practical ways to minimize its dehydrating effects and recover faster.

The Role of Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH)

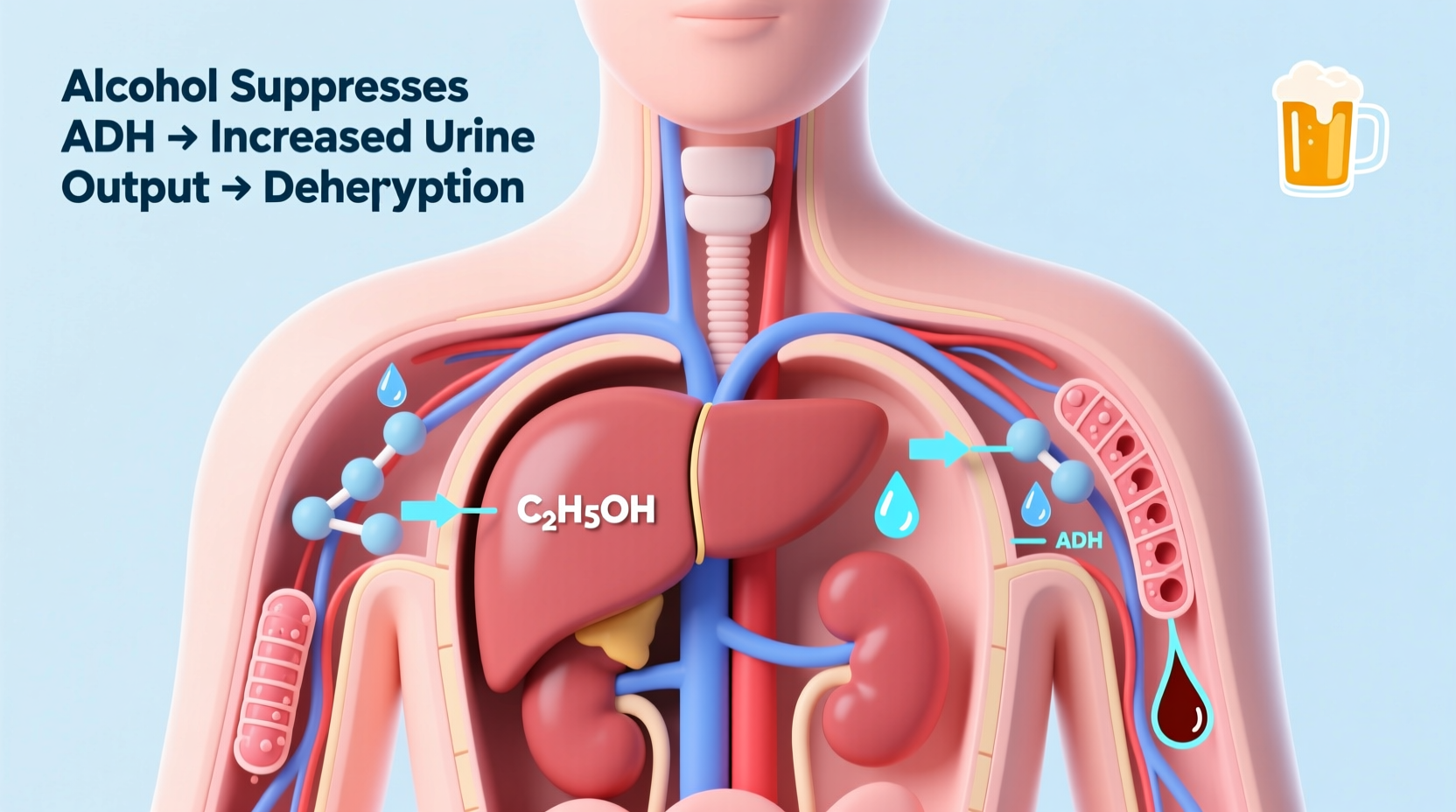

One of the primary reasons alcohol dehydrates you lies in its effect on a critical hormone: antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin. ADH is produced in the hypothalamus and released by the pituitary gland. Its main job is to signal the kidneys to reabsorb water back into the bloodstream, reducing urine output and conserving fluid.

When alcohol enters your system, it suppresses the release of ADH. Without sufficient levels of this hormone, your kidneys don’t reabsorb water effectively. Instead, they allow excess water to pass into the bladder, increasing urine production. This diuretic effect begins within 20 minutes of consuming alcohol and can last for several hours, depending on intake.

“Alcohol directly inhibits vasopressin secretion, turning your kidneys into overactive filters that flush out more water than necessary.” — Dr. Laura Simmons, Nephrology Researcher, Johns Hopkins Medicine

This means even if you drink a lot of liquid in the form of beer, wine, or cocktails, your body loses more fluid than it retains. Over time, this imbalance tips the scale toward net dehydration.

How Alcohol Affects Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Dehydration isn’t just about losing water—it also involves the loss of essential electrolytes like sodium, potassium, magnesium, and chloride. These minerals are crucial for nerve signaling, muscle function, and maintaining cellular hydration.

As alcohol increases urination, it doesn’t just remove water; it flushes out these vital electrolytes too. The result is an imbalance that contributes to symptoms such as dizziness, muscle cramps, and mental fog—common features of both acute dehydration and hangovers.

Additionally, alcohol irritates the gastrointestinal tract, which can lead to nausea and vomiting. When vomiting occurs, further fluid and electrolyte loss compounds the problem, accelerating dehydration.

Electrolyte Loss from Alcohol-Induced Urination

| Electrolyte | Function in Body | Effect of Alcohol-Induced Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | Regulates fluid balance and blood pressure | Low levels cause fatigue and confusion |

| Potassium | Supports heart and muscle function | Deficiency leads to cramps and weakness |

| Magnesium | Involved in over 300 enzyme reactions | Loss worsens headaches and sleep issues |

| Chloride | Maintains acid-base balance | Disruption affects overall metabolism |

Metabolic Byproducts and Their Impact on Hydration

Beyond its effect on hormones and electrolytes, alcohol itself is metabolized into substances that contribute to dehydration. Ethanol, the type of alcohol found in beverages, is broken down primarily in the liver through a two-step process:

- Step 1: Ethanol → Acetaldehyde (via alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme)

- Step 2: Acetaldehyde → Acetate (via aldehyde dehydrogenase)

Acetaldehyde is a toxic compound that causes inflammation, oxidative stress, and tissue damage. It also increases metabolic rate and body temperature, leading to insensible water loss through sweat and respiration. This subtle but continuous moisture loss adds to overall dehydration, especially during prolonged drinking sessions.

Moreover, acetate, while less harmful, alters brain energy metabolism and may indirectly influence thirst perception, making you less likely to recognize early signs of dehydration.

Real-World Example: A Night Out and Its Aftermath

Consider Mark, a 32-year-old office worker who attends a friend’s birthday dinner. Over the course of four hours, he consumes five pints of beer and two glasses of wine. He feels fine during the evening but skips drinking water, assuming the liquids in his drinks are sufficient.

By midnight, Mark has urinated at least six times—a clear sign of increased diuresis. The suppressed ADH levels mean his body isn’t conserving water. He goes home, sleeps poorly due to frequent nighttime bathroom trips, and wakes up at 8 a.m. feeling groggy, thirsty, and slightly nauseous.

His symptoms aren't just from alcohol toxicity—they're largely due to a 3–5% reduction in total body water, equivalent to mild dehydration. His headache stems from brain tissue shrinking slightly due to fluid loss, pulling away from the skull. His dry mouth reflects reduced saliva production, a side effect of low blood volume and altered autonomic function.

Mark’s experience illustrates how easily functional dehydration occurs—even without extreme binge drinking.

Strategies to Minimize Alcohol-Related Dehydration

You don’t have to give up alcohol entirely to avoid dehydration. With informed habits, you can reduce its impact significantly. Here’s a checklist of actionable steps:

- Drink a full glass of water before starting any alcoholic beverage

- Alternate between alcoholic drinks and water throughout the night

- Avoid salty snacks that increase thirst and fluid retention imbalance

- Limits drinks with higher alcohol content (e.g., spirits) which have stronger diuretic effects

- Rehydrate before bed with water or an electrolyte solution

- Get adequate sleep—poor recovery slows rehydration

Recovery Timeline: Rehydrating After Drinking

- Immediately after drinking: Consume 16–20 oz of water or electrolyte drink.

- Before sleep: Take another 8–12 oz of fluid; consider a banana or coconut water for potassium.

- Upon waking: Drink water first thing, even before coffee. Avoid caffeine initially, as it’s another diuretic.

- Morning routine: Eat a balanced breakfast with fruits and vegetables rich in water and minerals.

- Next 12–24 hours: Continue drinking fluids regularly—urine should be pale yellow.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does all alcohol dehydrate you equally?

No. The dehydrating effect correlates with alcohol concentration. Spirits like vodka or rum have high ABV and greater diuretic impact per serving than beer or wine. However, volume and speed of consumption also matter. Drinking four beers quickly will likely dehydrate more than slowly sipping one shot over hours.

Can drinking water prevent a hangover?

While water alone won’t eliminate a hangover—since acetaldehyde and inflammation play major roles—it significantly reduces severity. Staying hydrated helps maintain blood volume, supports liver detoxification, and minimizes headaches and fatigue. Combining hydration with rest and nutrition offers the best defense.

Are sports drinks better than water for rehydration after drinking?

Yes, in many cases. Sports drinks contain electrolytes like sodium and potassium that are lost through alcohol-induced urination. They also include carbohydrates that aid fluid absorption in the intestines. For moderate to heavy drinking, options like oral rehydration solutions (ORS) or coconut water are superior to plain water.

Conclusion: Understanding Leads to Better Choices

Alcohol dehydrates you not because it “soaks up” water, but because it disrupts hormonal control, accelerates fluid loss, and interferes with electrolyte balance. The science is clear: even moderate consumption triggers measurable dehydration. But awareness empowers change. By understanding how alcohol affects your physiology, you can make smarter choices—like pacing your drinks, prioritizing water, and replenishing electrolytes.

Hydration isn’t just about comfort; it’s foundational to cognitive clarity, physical performance, and long-term health. Whether you’re enjoying a casual drink or celebrating a special occasion, treating your body with care before, during, and after alcohol use makes a tangible difference.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?