Every time you feel an unusually warm winter day or hear about record-breaking global temperatures, the greenhouse effect is almost certainly involved. At the heart of this phenomenon lies carbon dioxide (CO₂), a seemingly simple molecule with an outsized impact on Earth’s climate. While CO₂ makes up less than 0.1% of the atmosphere, its ability to trap heat shapes the conditions for life on our planet. But how exactly does CO₂ trap heat? And why does such a small concentration have such a powerful effect?

This article breaks down the physics behind CO₂’s heat-trapping properties, explains the mechanics of the greenhouse effect, and explores what rising CO₂ levels mean for the future of our climate—all grounded in established atmospheric science.

The Basics of the Greenhouse Effect

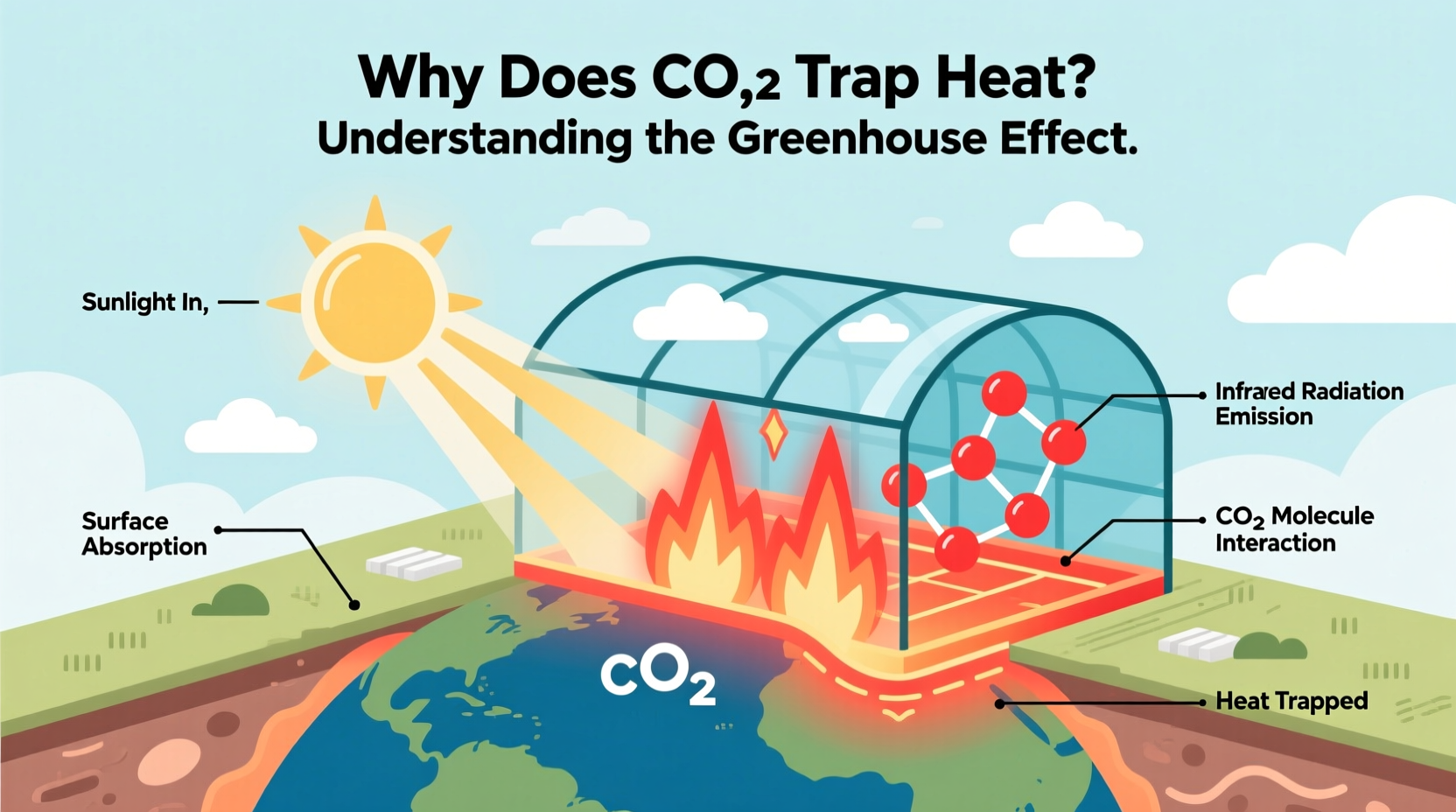

Sunlight reaches Earth as shortwave radiation, including visible light and ultraviolet rays. About 30% of this energy is reflected back into space by clouds, ice, and other reflective surfaces. The remaining 70% is absorbed by the land, oceans, and atmosphere, warming the planet.

As the surface heats up, it emits energy back toward space—but not in the same form. Instead, it radiates longwave infrared radiation (heat). This outgoing heat would escape freely if Earth had no atmosphere. However, certain gases in the air absorb and re-emit this infrared radiation, redirecting some of it back toward the surface. This natural process is the greenhouse effect, and without it, Earth’s average temperature would be around -18°C (0°F)—too cold for most life forms.

The key players in this heat-trapping system are greenhouse gases: water vapor (H₂O), carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and synthetic compounds like CFCs. Among these, CO₂ is especially significant due to its longevity in the atmosphere and the massive scale of human emissions.

How CO₂ Absorbs and Re-emits Heat

Not all gases interact with infrared radiation. Nitrogen (N₂) and oxygen (O₂), which make up 99% of the atmosphere, are largely transparent to both incoming sunlight and outgoing heat. But CO₂ has a molecular structure that allows it to vibrate when struck by specific wavelengths of infrared light.

When infrared radiation hits a CO₂ molecule, the bonds between its carbon and oxygen atoms stretch and bend. This absorbs the energy temporarily. Soon after, the molecule releases the energy by emitting another infrared photon—often in a random direction. Roughly half of this re-emitted energy travels back toward Earth’s surface, contributing to additional warming.

This absorption occurs at specific wavelengths—particularly around 15 micrometers—where Earth’s thermal radiation peaks. Satellites measuring outgoing radiation clearly show “dips” in emission at these wavelengths, confirming that CO₂ (and other greenhouse gases) are intercepting the heat trying to escape.

Why Small Amounts of CO₂ Have Big Effects

A common question is: How can such a trace gas—currently at about 420 parts per million—have such a dramatic influence? The answer lies in two factors: saturation and logarithmic forcing.

Early in the industrial era, even small increases in CO₂ caused significant warming because the atmosphere was not yet saturated at its primary absorption band. But as concentrations rise, each additional molecule has a slightly smaller effect—a principle known as logarithmic scaling. For example, the first 20 ppm of CO₂ causes more warming than the jump from 400 to 420 ppm.

However, this doesn’t mean rising CO₂ is harmless. Even with diminishing returns, the cumulative effect is substantial. Since pre-industrial times, CO₂ levels have increased by nearly 50%, trapping enough extra heat to raise global temperatures by over 1.2°C. Moreover, higher CO₂ concentrations broaden the absorption band slightly and affect less saturated regions of the spectrum, continuing to enhance warming.

“Carbon dioxide is like a thin coat that keeps getting thicker. Even if each new layer adds less warmth than the last, the overall result is still steadily rising temperatures.” — Dr. Michael E. Mann, Climate Scientist, University of Pennsylvania

Human Activities and the Acceleration of the Greenhouse Effect

Natural processes like volcanic eruptions and respiration release CO₂, but they are balanced by sinks such as photosynthesis and ocean absorption. Human activities, however, have disrupted this balance. Burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and cement production now emit over 37 billion tons of CO₂ annually—more than 100 times the amount released by volcanoes.

Because CO₂ lingers in the atmosphere for centuries, today’s emissions commit the planet to long-term warming. Ice core data shows that current CO₂ levels are higher than at any point in the past 800,000 years. This rapid change gives ecosystems and human societies little time to adapt.

Urban areas, industrial zones, and transportation networks are major sources, but so are everyday choices—like driving, heating homes with gas, and consuming goods with high carbon footprints. The cumulative impact is measurable: every ton of CO₂ emitted contributes approximately 0.0005°C to global warming over time.

Step-by-Step: How Human CO₂ Emissions Warm the Planet

- Fossil fuels are burned for energy in power plants, vehicles, and industry.

- CO₂ is released into the atmosphere, increasing its concentration.

- More CO₂ molecules absorb and re-radiate infrared energy emitted by Earth.

- Downward radiation increases, reducing the net heat loss to space.

- Energy imbalance leads to planetary warming, melting ice, raising sea levels, and altering weather patterns.

Comparing Greenhouse Gases: A Closer Look

While CO₂ is the most discussed greenhouse gas, others play critical roles. The following table compares major greenhouse gases by their heat-trapping ability and lifespan:

| Gas | Global Warming Potential (100-year) | Atmospheric Lifetime | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | 1 (baseline) | Centuries (up to 1,000 years) | Fossil fuels, deforestation, cement production |

| Methane (CH₄) | 28–36 | ~12 years | Livestock, landfills, oil/gas leaks |

| Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) | 265–298 | ~114 years | Fertilizers, combustion, industrial processes |

| Water Vapor (H₂O) | Varies (feedback, not direct driver) | Days to weeks | Evaporation (amplifies warming) |

Note that while methane is far more potent per molecule, CO₂ dominates climate change due to its sheer volume and persistence. Water vapor acts as a feedback: as temperatures rise, warmer air holds more moisture, which amplifies the greenhouse effect—but only after initial warming from CO₂ or other drivers.

Real-World Impact: The Case of the Arctic

The Arctic provides a stark example of CO₂-driven warming. Over the past 50 years, temperatures there have risen nearly three times faster than the global average—a phenomenon known as polar amplification. Sea ice, which reflects sunlight, is shrinking rapidly. As dark ocean water is exposed, it absorbs more heat, accelerating warming in a self-reinforcing loop.

In 2020, Siberia recorded a temperature of 38°C (100°F) north of the Arctic Circle—an event virtually impossible without human-induced climate change. Scientists attribute much of this extreme warming to elevated CO₂ levels trapping more heat and disrupting atmospheric circulation patterns.

This isn’t just a remote problem. Melting ice contributes to sea-level rise, threatening coastal cities. Changes in jet streams affect weather across North America, Europe, and Asia, leading to prolonged droughts, intense storms, and unpredictable growing seasons.

FAQ: Common Questions About CO₂ and the Greenhouse Effect

Doesn’t water vapor trap more heat than CO₂?

Yes, water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas and contributes more to the natural greenhouse effect. However, its concentration depends on temperature—it acts as a feedback, not a primary driver. CO₂ initiates warming, which then increases evaporation and water vapor levels, amplifying the effect.

If CO₂ is natural, why is it a problem now?

CO₂ is natural, but the current rate of increase is unprecedented. Natural cycles cause CO₂ fluctuations over thousands of years. Human activity has raised levels by 50% in just 200 years—far too fast for natural systems to balance.

Can plants absorb all the extra CO₂?

Plants and oceans currently absorb about half of human CO₂ emissions. But forests are being cleared, and oceans are becoming more acidic, reducing their capacity. Relying on natural sinks alone is not sustainable.

What You Can Do: A Simple Action Checklist

- Reduce energy use at home: switch to LED bulbs, improve insulation, unplug devices.

- Choose renewable energy providers or install solar panels if possible.

- Limit car travel; walk, bike, carpool, or use public transit.

- Eat less meat, especially beef, which has a high carbon footprint.

- Support policies that promote clean energy, reforestation, and carbon pricing.

- Educate others—share reliable information about climate science.

Conclusion: Understanding Is the First Step Toward Action

CO₂ traps heat because of its unique ability to interact with infrared radiation—a property rooted in basic physics, confirmed by decades of observation and experimentation. The greenhouse effect is essential for life, but human-driven increases in CO₂ are pushing it beyond natural limits, destabilizing the climate system.

Understanding the science removes confusion and empowers informed decisions. From personal habits to civic engagement, everyone has a role in reducing emissions and building resilience. The challenge is immense, but so is the opportunity—to create a cleaner, healthier, and more stable world for future generations.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?