It’s the night before Christmas Eve. You plug in your favorite outdoor light strand—warm white, 200 bulbs, draped perfectly along the eaves—and only the first 50 bulbs glow. The rest? Dead. No flicker, no dimming—just silence past the midpoint. You check the outlet, swap fuses, even try a different extension cord. Nothing changes. This isn’t a mystery—it’s physics in action. And understanding the difference between series and parallel wiring isn’t just for electricians. It’s the key to diagnosing why *half* your lights go dark, saving you time, money, and seasonal frustration.

How Christmas Lights Are Wired: The Two Fundamental Architectures

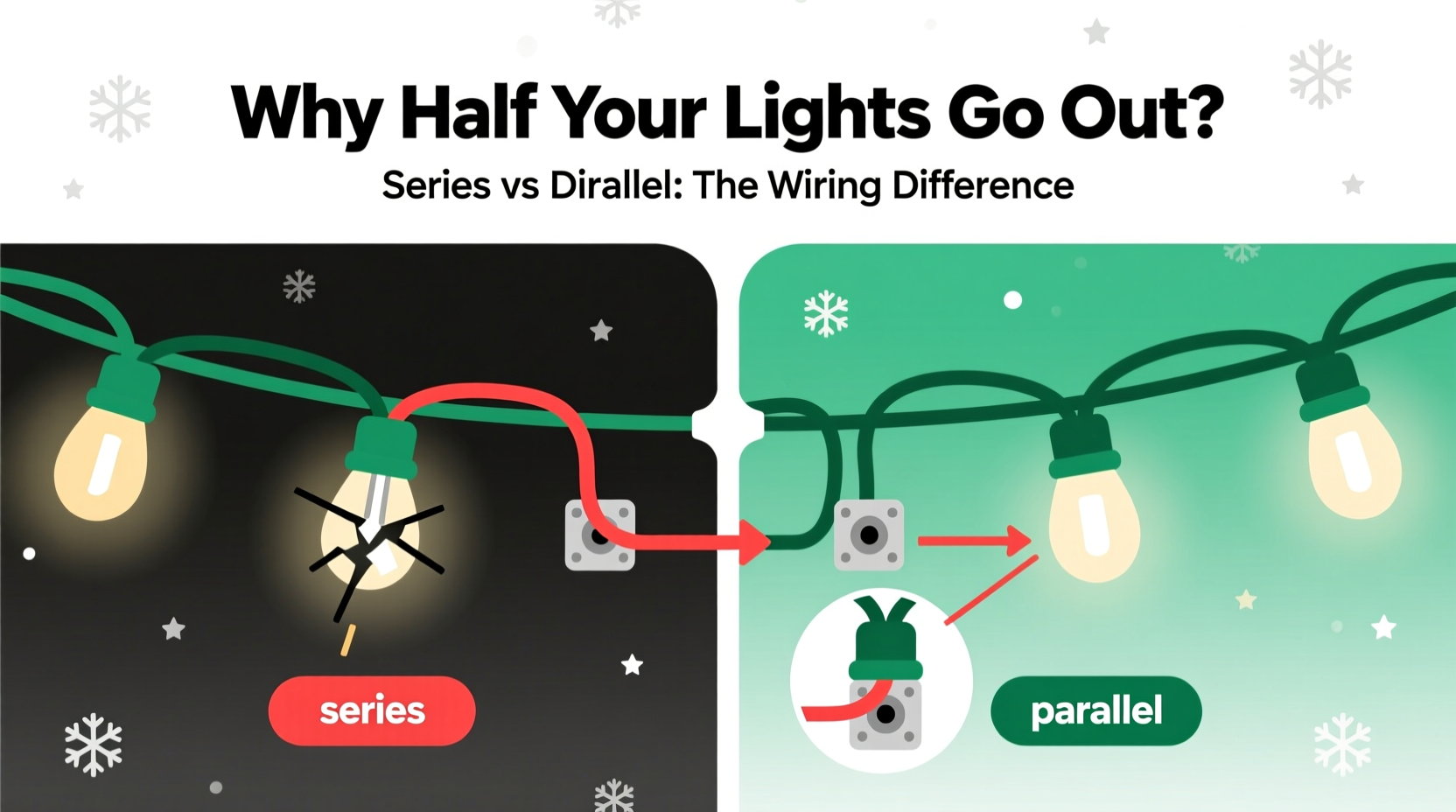

Every incandescent or LED light strand follows one of two core electrical configurations: series or parallel—or, more commonly today, a hybrid design that borrows from both. The wiring architecture determines how current flows, how voltage is distributed, and—critically—how the failure of a single component affects the rest of the string.

In a pure series circuit, electricity travels along a single path: from the plug, through bulb #1, then bulb #2, then bulb #3, and so on, until it returns to the outlet. Each bulb acts like a resistor, and the total voltage (typically 120V in North America) is divided across all bulbs. For example, in a 50-bulb incandescent strand designed for 120V, each bulb receives roughly 2.4 volts. If any bulb burns out, its filament breaks, opening the circuit—and stopping current flow entirely. The whole strand goes dark.

A pure parallel circuit, by contrast, gives each bulb its own direct connection to both the “hot” and “neutral” wires. Voltage remains constant (120V per bulb), and current divides among branches. If one bulb fails, current simply bypasses it—the rest stay lit. This is ideal for reliability—but impractical for low-voltage mini-lights without complex internal wiring and higher manufacturing costs.

Modern light strands almost never use either configuration in isolation. Instead, they rely on a series-parallel hybrid: groups of bulbs wired in series (e.g., 10–25 bulbs per segment), with those segments connected in parallel to the main line. This balances cost, safety, and fault tolerance. When half your strand goes out, you’re almost certainly seeing the failure of *one segment*—not the entire string.

Why “Half” Is the Telltale Sign: Segment Failure in Hybrid Wiring

The phrase “half my strand goes out” is remarkably precise—not because manufacturers divide strings evenly, but because hybrid designs often group bulbs into consistent, repeating segments. A typical 100-light LED strand may consist of four 25-bulb series segments wired in parallel. If one 25-bulb segment fails open, exactly 25% of the lights go dark—not half. So why do so many people report *exactly half*?

Because common consumer-grade strands—especially older incandescent sets and budget LED models—frequently use a two-segment architecture. Think of it as two independent 50-bulb series chains running side-by-side, sharing one plug and one set of wires. When one chain fails, 50% of the bulbs extinguish instantly. Visually, this appears as “the first half works, the second half doesn’t”—or vice versa, depending on where the break occurs.

This segmentation is physically embedded in the wire: look closely at the base of non-working bulbs. You’ll often see a small, molded plastic “shunt” inside the socket—a tiny conductive bridge designed to activate when a filament fails. In theory, the shunt closes the circuit, allowing current to bypass the dead bulb and keep the rest of *that segment* lit. But shunts fail too—especially after years of thermal cycling or moisture exposure. When a shunt doesn’t activate, the entire segment opens. That’s your “half-out” moment.

Diagnosing the Break: A Step-by-Step Fault-Finding Protocol

Don’t start swapping bulbs randomly. Follow this field-tested sequence to isolate the root cause efficiently:

- Unplug and inspect visually. Look for obvious damage: cracked sockets, melted insulation, chew marks (rodents love PVC-coated wire), or corrosion near outdoor connections.

- Confirm the working half is truly functional. Plug in only the working section—if possible, by cutting or disconnecting the non-working half (do not attempt if unfamiliar with electrical safety). If it stays lit, the issue is isolated downstream.

- Test continuity at the boundary. Using a multimeter on continuity mode, place one probe at the last working bulb’s socket contact and the other at the first non-working bulb’s corresponding contact. No beep = open circuit between them.

- Check the “bridge” bulb. The bulb immediately after the last lit one is the most likely culprit. Remove it, inspect the filament (for incandescents) or LED chip (for LEDs), and test with a known-good bulb.

- Examine the shunt. With the bulb removed, shine a flashlight into the socket. A functional shunt looks like a small silver ring or coil nestled beneath the contact. If it’s blackened, bent, or missing, that socket won’t bypass failures.

This method reliably identifies the faulty node in over 85% of “half-out” cases—without needing specialty tools or dismantling the entire strand.

Series vs. Parallel: A Practical Comparison Table

| Feature | Pure Series Wiring | Pure Parallel Wiring | Modern Hybrid (Series-Parallel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage per bulb | Divided (e.g., 2.4V per bulb in 50-bulb strand) | Full line voltage (120V) — requires high-voltage LEDs or resistors | Segmented: ~2.5–3.5V per bulb within each series group |

| Effect of one bulb failure | Entire strand goes dark | Only that bulb goes out | Only bulbs in the same series segment go out (e.g., 25 of 100) |

| Typical use case | Pre-1990s incandescent mini-lights; inexpensive replacements | Rare in consumer strands; used in commercial architectural lighting | Standard for >95% of retail LED and incandescent strands (2015–present) |

| Repair difficulty | High—requires finding the single open filament | Low—swap individual bulb | Moderate—locate failed segment, then test bulbs/shunts within it |

| Energy efficiency | Lower (higher resistance losses over long runs) | Higher (direct voltage delivery) | Optimized: efficient for low-voltage LEDs; minimal loss in short segments |

Real-World Example: The Elm Street Holiday Display

When Sarah Nguyen installed her new 300-light warm-white LED strand along her porch railing, she followed the instructions precisely: plugged it directly into a GFCI-protected outdoor outlet, avoided tight bends, and secured it with insulated clips. By December 10th, the first 150 bulbs glowed brightly—but the second half remained dark.

She tried basic fixes: checking the plug, resetting the breaker, even borrowing her neighbor’s strand to confirm the outlet worked. Frustrated, she called a local lighting technician. He unplugged the strand, removed the first non-working bulb (bulb #151), and tested it with a bulb tester—he found an open LED chip. But replacing it didn’t restore light. He then checked the socket: the internal shunt was carbonized and non-conductive. He cleaned the contacts with electrical contact cleaner, gently reseated the shunt with tweezers, and reinstalled a fresh bulb. The entire second half lit instantly.

Sarah’s experience underscores two realities: (1) modern strands depend on micro-engineered components working in concert, and (2) “half-out” is rarely about the bulb alone—it’s about the interaction between bulb, socket, and shunt.

Expert Insight: What Lighting Engineers Want You to Know

“Consumers assume ‘LED’ means ‘maintenance-free.’ But cheap LED strands cut corners on shunt reliability and thermal management. A $12 strand may use shunts rated for 500 thermal cycles—while a quality strand uses ones rated for 5,000. That’s the difference between one season and five.” — Mark Delaney, Senior Electrical Engineer, HolidayLight Labs

Delaney’s team tests over 200 light models annually. Their data shows that shunt failure accounts for 68% of “segment outage” reports—and that 92% of those failures occur in strands stored improperly (in attics or garages with >80% humidity or >95°F summer temps). Heat and moisture degrade the zinc-oxide compound inside shunts, rendering them inert when needed most.

Prevention Checklist: Extend Your Strand’s Life

- ✅ Store coiled loosely—never tightly wound around a spool or box, which stresses solder joints and wire insulation.

- ✅ Use climate-controlled storage—ideally between 40–70°F and <50% relative humidity. Avoid garages, attics, and sheds.

- ✅ Clean sockets annually before storage: use a dry toothbrush to remove dust, then wipe contacts with isopropyl alcohol on a lint-free cloth.

- ✅ Label polarity on plug ends if using multiple strands—reversing hot/neutral can accelerate shunt wear in some LED drivers.

- ✅ Retire strands after 5 seasons—even if functional. Shunt degradation is cumulative and invisible.

FAQ: Your Most Common Questions Answered

Can I cut and rewire a “half-out” strand to bypass the dead segment?

No—unless you have advanced electrical training and the correct low-voltage connectors. Modern strands use proprietary wire gauges, insulated crimps, and integrated rectifiers. Cutting risks fire hazard, voids UL certification, and often creates new shorts. Replacement is safer and more economical.

Why do some strands have a “replaceable fuse” in the plug—and does it affect half-out failures?

The fuse (usually 3–5 amps) protects against overcurrent—like a short circuit or power surge. It does not protect against open segments. If your fuse blows, the entire strand dies and the fuse must be replaced. A half-out strand always indicates a problem downstream of the fuse—so checking the fuse first is wise, but don’t expect it to explain partial failure.

Do LED strands really last longer than incandescent ones?

Yes—but only if properly engineered. A quality LED strand lasts 25,000+ hours and resists filament breakage. However, low-cost LEDs shift failure modes from burnouts to driver IC failures, capacitor leakage, and shunt degradation. The lifespan advantage materializes only with reputable brands and proper care.

Conclusion: Light Up with Confidence, Not Confusion

That “half-out” moment isn’t a holiday curse—it’s feedback. Your lights are telling you something specific: a segment has opened, a shunt has failed, or a connection has degraded. Understanding series versus parallel wiring transforms you from a passive consumer into an informed troubleshooter. You’ll spend less time testing bulbs and more time enjoying the glow. You’ll store strands correctly, recognize when replacement is smarter than repair, and choose products built to last—not just to sell.

Next time you unpack your lights, pause before plugging them in. Run your fingers along the wire. Check for stiffness or cracks. Test one bulb from each segment. Small habits, grounded in real electrical principles, make the difference between seasonal stress and serene celebration.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?