At first glance, it might seem like a simple observation—ice cubes bob in a glass of water, lakes freeze from the top down, and icebergs drift across oceans. But beneath this everyday phenomenon lies a profound scientific anomaly: water is one of the very few substances whose solid form is less dense than its liquid state. This rare behavior isn’t just a curiosity; it’s a cornerstone of life as we know it. Understanding why ice floats reveals deep insights into molecular structure, thermal dynamics, and environmental stability.

The Role of Density in Floating

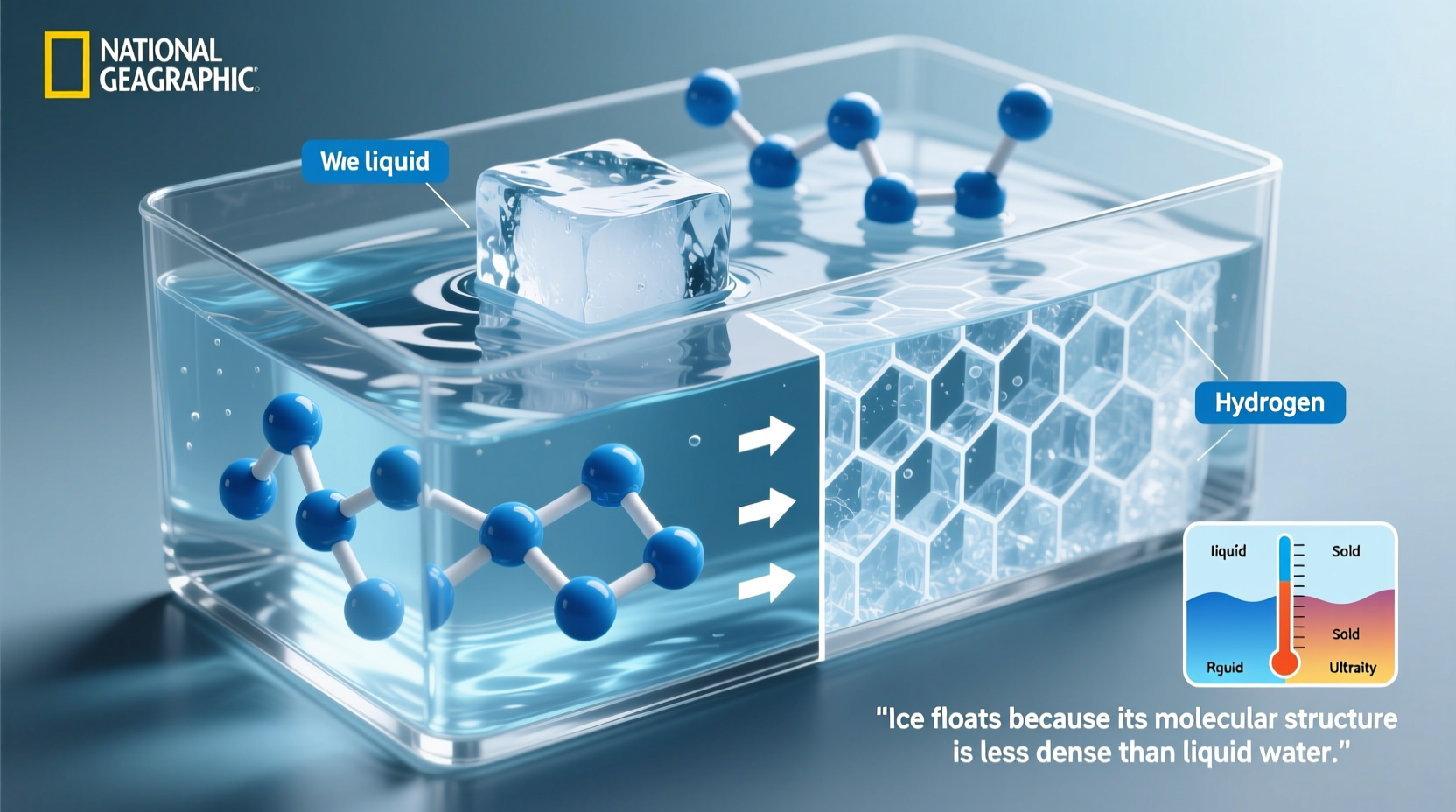

Density determines whether an object sinks or floats in a fluid. An object will float if it is less dense than the liquid it displaces. For most substances, the solid phase is denser than the liquid because molecules pack more tightly when cooled. But water defies this norm. When water freezes into ice, its molecules arrange into a rigid, open hexagonal lattice that occupies more space than in the liquid form. This expansion reduces the overall density of ice by about 9% compared to liquid water at 4°C.

This shift means that for the same mass, ice takes up more volume. As a result, ice has a density of approximately 0.917 g/cm³, while liquid water measures around 0.9998 g/cm³ near freezing. That small difference is enough to allow ice to remain buoyant—a principle known as Archimedes’ buoyancy law.

Molecular Behavior: Hydrogen Bonding and Expansion

The reason water expands upon freezing lies in its molecular structure. A water molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom (H₂O), forming a bent shape with a partial positive charge on the hydrogens and a negative charge on the oxygen. These polar characteristics enable strong intermolecular attractions called hydrogen bonds.

In liquid water, hydrogen bonds constantly form and break due to thermal motion, allowing molecules to move freely and pack relatively closely. But as temperature drops below 4°C, kinetic energy decreases, and molecules begin to align into a stable crystalline structure. Each water molecule forms four hydrogen bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, creating a hexagonal network full of empty spaces.

This ordered lattice pushes molecules farther apart than they are in the disordered liquid state, increasing volume and decreasing density. The process begins gradually as water cools toward 4°C—the point of maximum density—but accelerates dramatically during the phase change to ice.

“Water’s anomalous expansion upon freezing is not just unusual—it’s essential. Without it, lakes would freeze solid from the bottom up, making aquatic life impossible.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Physical Chemist, University of Colorado

Environmental and Biological Implications

The fact that ice floats has far-reaching consequences for ecosystems and climate systems. In winter, when surface water cools and eventually freezes, the resulting ice layer acts as an insulating barrier. It slows further heat loss from the underlying water, protecting fish, plants, and microorganisms beneath.

If ice sank instead of floated, bodies of water would freeze progressively from the bottom upward. Over time, especially in colder climates, entire lakes and rivers could turn into solid ice blocks, eliminating habitats and disrupting nutrient cycles. Seasonal thawing might not be sufficient to restore liquid conditions each year, leading to long-term ecological collapse.

On a planetary scale, floating sea ice plays a crucial role in regulating Earth’s albedo—the amount by which sunlight is reflected back into space. Ice reflects up to 80% of incoming solar radiation, whereas open ocean absorbs over 90%. This feedback mechanism helps stabilize global temperatures. As climate change reduces polar ice cover, more heat is absorbed, accelerating warming—a process known as the ice-albedo feedback loop.

Practical Applications and Real-World Observations

Understanding why ice floats extends beyond textbooks. Engineers designing underwater structures must account for ice pressure and buoyancy forces in cold regions. Scientists studying exoplanets consider water’s phase behavior when assessing potential habitability. Even in food preservation, the expansion of freezing water explains why unopened bottles can burst in the freezer.

Mini Case Study: Winter Fish Survival in Northern Lakes

In Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area, lakes routinely freeze over for months. Despite air temperatures dropping below -20°C, lake trout and other species survive beneath the ice. Biologists monitoring these ecosystems have found that the persistent ice cover maintains water temperatures just above freezing at depth. The insulating effect of floating ice prevents complete freezing, preserving dissolved oxygen levels and enabling respiration. Without this natural insulation provided by buoyant ice, winterkill events—where fish die due to lack of oxygen—would occur far more frequently and severely.

Do’s and Don’ts of Understanding Water’s Unique Properties

| Action | Recommended? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Cool water slowly to observe density changes | ✅ Yes | Allows observation of convection currents and stratification |

| Freeze water in sealed containers | ❌ No | Expansion can cause cracking or explosion |

| Compare ice behavior in different liquids | ✅ Yes | Demonstrates relative density principles |

| Assume all solids sink in their liquids | ❌ No | Ice is a key exception due to hydrogen bonding |

| Use distilled water for freezing experiments | ✅ Yes | Minimizes impurities that affect nucleation and clarity |

Step-by-Step Guide: Demonstrating Why Ice Floats

- Gather materials: Clear glass, tap water, ice cube, food coloring (optional).

- Fill the glass nearly full with cold water. Avoid using warm water to prevent rapid melting.

- Add a drop of food coloring to help visualize displacement and mixing patterns.

- Gently place an ice cube on the surface. Observe how it settles with roughly 1/10th above waterline.

- Watch as the ice melts. Notice that the water level remains constant—proof that the floating ice already displaced its equivalent volume.

- Repeat with saltwater (mix 35g salt per liter). Ice floats even higher due to increased liquid density.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn't water behave like other liquids when it freezes?

Most liquids contract when cooled because molecules slow down and pack more tightly. Water contracts until 4°C, but below that, hydrogen bonding dominates and forces molecules into an open hexagonal structure. This structural shift causes expansion rather than contraction, making solid water less dense than liquid water—an anomaly shared only by a few substances like silicon, gallium, and bismuth.

Would life exist if ice sank instead of floated?

It’s highly unlikely that complex aquatic ecosystems would have evolved if ice sank. Permanent or deep freezing of water bodies would eliminate stable environments for early life forms. Many scientists argue that water’s density anomaly was a prerequisite for the development of life on Earth, particularly in temperate and polar zones.

Does adding impurities change whether ice floats?

Salt lowers the freezing point of water and increases the density of the liquid phase. In seawater, ice still floats, but slightly higher than in freshwater because saltwater is denser. However, extremely salty solutions (like brines) can alter crystal formation and may lead to different behaviors under extreme conditions.

Conclusion: Embracing Water’s Anomaly

The floating of ice on water is not merely a physical oddity—it’s a foundational element of Earth’s biosphere. From microscopic hydrogen bonds to vast polar ice sheets, this single property influences weather, biology, and planetary resilience. Recognizing the science behind such ordinary phenomena fosters deeper appreciation for nature’s intricate design.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?