Rain is one of the most fundamental elements of Earth’s weather system. It sustains life, replenishes water sources, and shapes ecosystems. Yet, despite its familiarity, the process that leads to rainfall involves a complex interplay of atmospheric conditions, temperature shifts, and physical transformations. Understanding why it rains goes beyond simply noticing clouds in the sky—it requires exploring the hydrological cycle, air mass dynamics, and the microscopic processes within clouds.

This article breaks down the science of rainfall in clear, practical terms, explaining how water moves from oceans to atmosphere to land, what triggers precipitation, and how human activity influences rain patterns. Whether you're curious about daily weather forecasts or concerned about long-term climate trends, this guide provides foundational knowledge with real-world relevance.

The Water Cycle: Nature’s Rain Engine

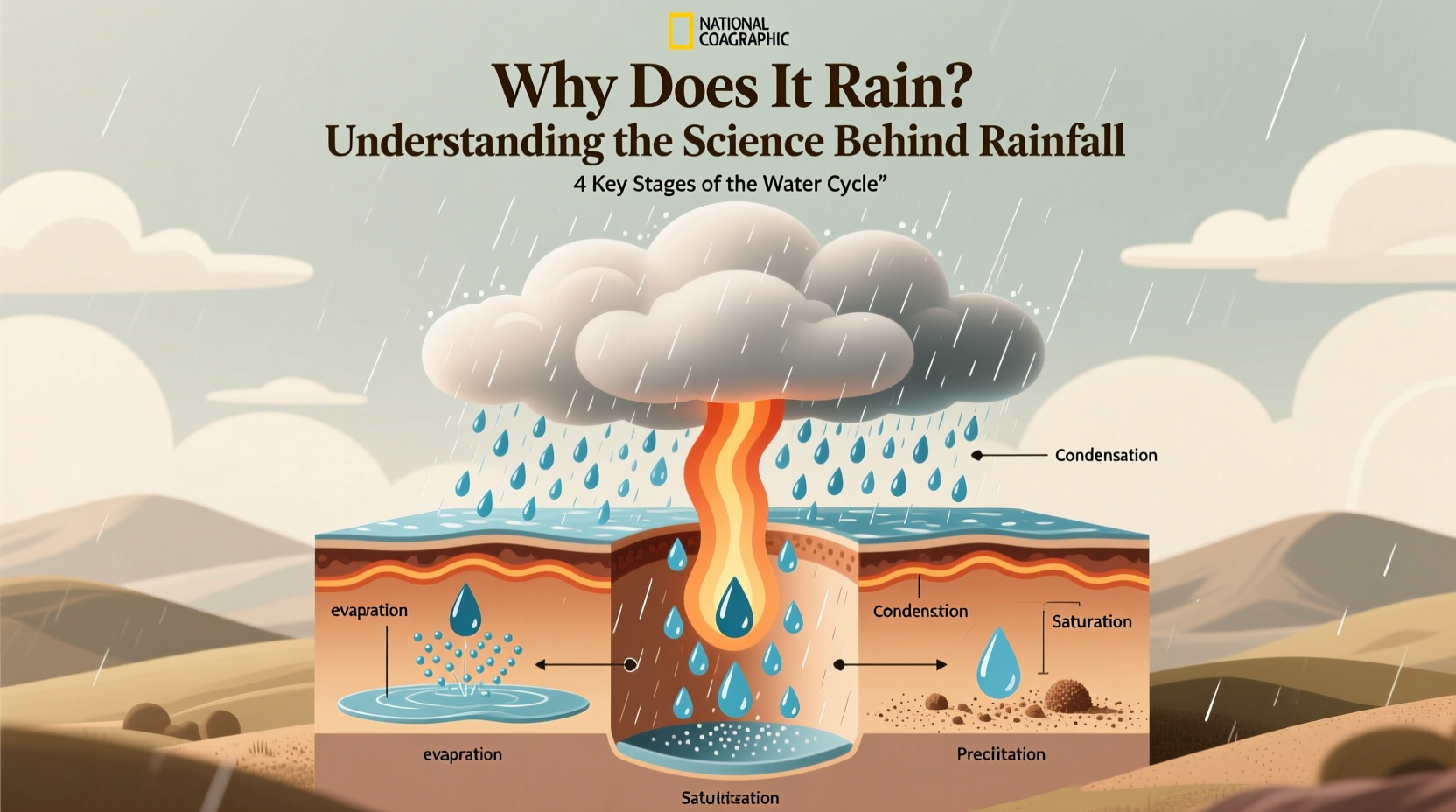

At the heart of all rainfall is the water cycle—a continuous process that circulates water across the planet. This cycle consists of four primary stages: evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and collection.

- Evaporation: Solar energy heats surface water from oceans, lakes, and rivers, turning liquid into vapor that rises into the atmosphere.

- Transpiration: Plants also release moisture through their leaves, contributing additional water vapor.

- Condensation: As warm, moist air ascends, it cools. When it reaches the dew point, water vapor condenses around tiny particles like dust, forming clouds.

- Precipitation: Once cloud droplets grow large enough, gravity pulls them down as rain, snow, sleet, or hail.

- Collection: Water returns to bodies of water or soaks into soil, restarting the cycle.

The balance of this system ensures that freshwater is distributed globally. Disruptions—such as deforestation or urban heat islands—can alter local rainfall patterns by changing evaporation rates or airflow.

How Clouds Produce Rain: From Droplets to Downpours

Not all clouds produce rain. The ability to generate precipitation depends on cloud type, altitude, temperature, and internal dynamics. Two key mechanisms explain how tiny droplets become raindrops:

- The Collision-Coalescence Process: In warmer clouds (typically below 5 km), larger droplets fall faster than smaller ones, colliding and merging with them. This creates progressively heavier drops until they fall as rain.

- The Bergeron-Findeisen Process: In colder, high-altitude clouds containing ice crystals and supercooled water droplets, ice grows at the expense of liquid because of differences in saturation vapor pressure. These crystals become heavy and may melt into raindrops as they descend.

These microphysical processes are influenced by atmospheric stability, humidity levels, and the presence of condensation nuclei—microscopic particles such as sea salt, pollen, or pollution that serve as surfaces for water to condense upon.

“Rain doesn’t just fall from the sky—it’s built drop by drop inside clouds through precise physical laws.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Atmospheric Scientist, NOAA

Weather Systems That Trigger Rainfall

Rain rarely occurs in isolation. It's typically driven by larger meteorological systems that force moist air to rise, cool, and condense. The three most common lifting mechanisms are:

| Mechanism | How It Works | Example Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Orographic Lifting | Air forced upward over mountains cools and releases moisture on the windward side | Western coast of North America, Himalayas |

| Frontal Lifting | Warm and cold air masses collide; warm air rises over denser cold air | Mid-latitude zones (e.g., Europe, U.S. Midwest) |

| Convectional Lifting | Surface heating causes warm air to rise rapidly, forming thunderstorms | Tropics, summer afternoons inland |

Each system produces distinct rain characteristics. Orographic rain tends to be steady and prolonged, frontal systems bring widespread showers, and convectional rain often comes in intense bursts with lightning.

Mini Case Study: Seattle’s Persistent Drizzle

Seattle receives abundant rainfall—not from tropical storms, but due to consistent orographic and frontal lifting. Moist Pacific air hits the Olympic Mountains, forcing uplift and condensation. Meanwhile, frequent mid-latitude cyclones push warm fronts over cooler coastal air, creating layered cloud decks that yield days of light rain. Locals experience “liquid sunshine” not because of extreme weather, but because of geography meeting prevailing wind patterns.

Human Impact on Rainfall Patterns

While natural forces dominate rainfall, human activities increasingly influence where, when, and how much it rains. Urbanization, agriculture, and emissions alter both local and global climates.

- Urban Heat Islands: Cities absorb more heat than rural areas, enhancing convection and increasing thunderstorm frequency downwind.

- Aerosol Pollution: Excess particulates can suppress rain by creating too many small droplets that don’t coalesce efficiently—or enhance it by providing more nuclei for condensation.

- Deforestation: Reduces transpiration, lowering regional humidity and potentially decreasing rainfall over time.

In some regions, cloud seeding is used to artificially induce rain by dispersing silver iodide into clouds, encouraging ice crystal formation. Though controversial, it has been deployed during droughts in places like California and China.

Step-by-Step: How a Thunderstorm Develops

- Sun heats ground: Intense solar radiation warms the Earth’s surface, especially in open fields or urban areas.

- Warm air rises: Thermals carry moisture upward in unstable air layers.

- Cloud formation: Rising air cools and condenses, forming cumulus clouds.

- Mature stage: Updrafts and downdrafts coexist; rain begins, often accompanied by lightning and gusty winds.

- Dissipation: Cool downdrafts cut off the supply of warm air, weakening the storm.

This entire lifecycle can last 30 minutes to an hour, producing short but heavy rainfall. Monitoring these stages helps meteorologists issue timely warnings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can it rain without clouds?

No—rain must originate from clouds, though sometimes precipitation evaporates before reaching the ground (called virga). What appears to be rain from clear skies is usually wind-blown spray or mist.

Why do some rainy days feel humid while others feel crisp?

Humidity depends on the source of the air mass. Tropical systems bring moist, sticky rain, while cold fronts deliver cooler, drier air post-rainfall, making the environment feel cleaner and less muggy.

Is acid rain still a problem today?

Yes, though significantly reduced in many countries due to stricter emissions controls. Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides from industry and vehicles can still create acidic precipitation, harming aquatic life and vegetation, particularly in industrial regions.

Conclusion: Embracing the Rhythm of Rain

Rain is far more than a weather event—it’s a vital link in Earth’s ecological chain. From the invisible dance of molecules in a cloud to the sweeping motion of storm fronts, the science behind rainfall reveals a dynamic, interconnected system shaped by nature and increasingly influenced by human choices. By understanding how and why it rains, we gain deeper appreciation for the environment and better insight into adapting to changing climate patterns.

Next time clouds gather, take a moment to consider the journey each drop has made—from ocean to sky to street. Knowledge transforms passive observation into active awareness.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?