Sourdough bread is a rewarding craft, but for many beginners, the dream of a light, airy loaf often ends in disappointment. You follow a recipe, wait hours, and still end up with a dense, flat disk instead of a beautifully risen boule. The good news? Most failures are due to predictable, fixable issues—not magic or luck. Understanding why your sourdough isn’t rising comes down to mastering a few key elements: starter health, dough temperature, fermentation timing, gluten development, and proper shaping. This guide breaks down the most common beginner errors and gives you actionable solutions to achieve consistent, oven-spring success.

1. Your Sourdough Starter Isn’t Active Enough

The foundation of every great sourdough loaf is a healthy, active starter. If your starter lacks strength, your bread won’t rise—no matter how perfect the rest of your process is. A weak starter doesn’t produce enough carbon dioxide to leaven the dough effectively.

A truly active starter should double in volume within 4–8 hours after feeding, have a bubbly, frothy texture, and emit a tangy but pleasant aroma—like yogurt or ripe fruit. If it’s sluggish, separates into liquid (hooch), or smells like acetone, it’s underfed or stressed.

Signs of an Underperforming Starter

- Takes longer than 12 hours to peak after feeding

- No visible bubbles or foam on the surface

- Dough sinks when dropped into water (float test fails)

- Strong alcoholic or nail-polish-like odor

“Your starter should be at its peak—just before it begins to fall—when added to dough. That’s when yeast and bacteria are most active.” — Ken Forkish, artisan baker and author of *Flour Water Salt Yeast*

2. Inadequate Gluten Development

Gluten is the protein network that traps gas produced by your starter. Without sufficient gluten strength, the dough can’t hold air, leading to poor rise and a dense crumb. Many beginners underestimate how crucial proper mixing and kneading are—even in no-knead recipes.

While traditional kneading builds gluten quickly, most modern sourdough methods rely on stretch-and-fold techniques during bulk fermentation. Skipping or reducing these folds compromises structure. Dough should evolve from sticky and slack to smooth, elastic, and capable of forming a thin “windowpane” when stretched gently between fingers.

How to Improve Gluten Development

- Use high-protein bread flour: Aim for at least 12% protein content. All-purpose flour works, but bread flour yields stronger gluten.

- Autolyse your dough: Mix flour and water and let rest for 30–60 minutes before adding salt and starter. This allows gluten strands to form naturally.

- Perform regular stretch-and-folds: During the first 2–3 hours of bulk fermentation, perform a set of stretches every 30 minutes. Gently pull one side of the dough upward and fold it over itself, rotating the bowl each time.

- Check windowpane test: After several folds, take a small piece and gently stretch it. If it forms a translucent membrane without tearing, gluten is well-developed.

| Factor | Supports Gluten | Hinders Gluten |

|---|---|---|

| Flour Type | Bread flour, high-protein | Cake flour, low-gluten blends |

| Hydration | 65–75% hydration manageable for beginners | Over 80% hydration hard to handle and shape |

| Mixing Method | Stretch-and-folds, slap-and-fold | Minimal mixing, no folds |

| Salt Timing | Added after autolyse | Too early or too late |

3. Fermentation Is Off: Too Cold, Too Long, or Too Short

Fermentation is where flavor and rise happen—but timing and temperature are everything. Sourdough is sensitive to environment. If your kitchen is too cold, fermentation slows dramatically. If it's too warm, the starter burns through food too fast, exhausting itself before baking.

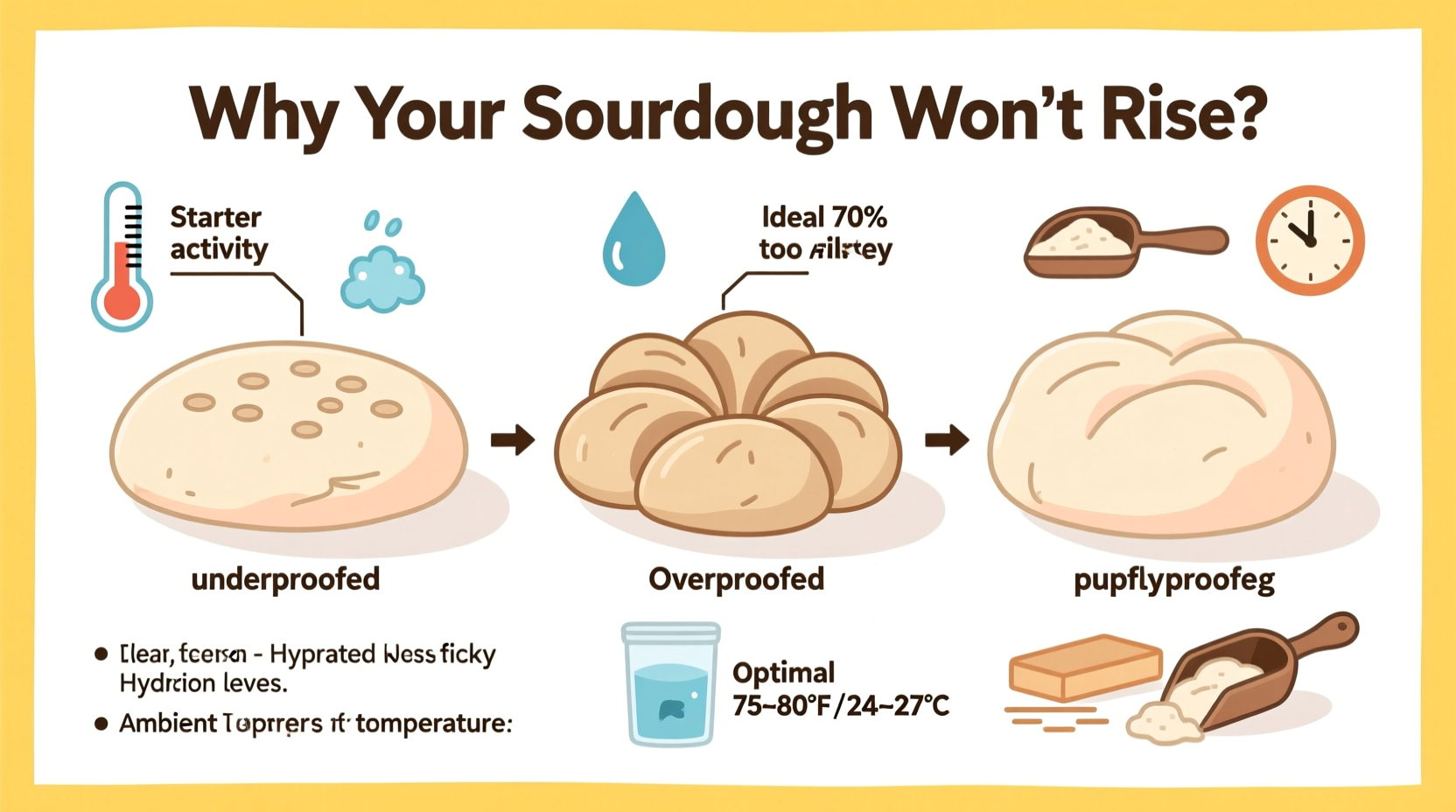

Bulk fermentation typically takes 4–6 hours at 74–78°F (23–26°C). At cooler temperatures (below 70°F), it may take 8–12 hours. Signs of proper fermentation include increased volume (50–100%), bubbles throughout, and a jiggly, aerated texture. Under-fermented dough lacks gas; over-fermented dough collapses and becomes sticky and sour.

Common Fermentation Mistakes

- Assuming fermentation time is fixed rather than based on dough behavior

- Letting dough ferment near drafts or cold countertops

- Using tap water with chlorine, which inhibits microbial activity

- Not adjusting for seasonal temperature changes

Step-by-Step Guide: Optimal Fermentation Environment

- Feed your starter 4–8 hours before mixing dough, ensuring it peaks just as you begin.

- Mix dough and perform autolyse (flour + water only) for 30 minutes.

- Add starter and salt, mix well, then begin stretch-and-folds every 30 minutes for 2–3 hours.

- Let dough rest at room temperature (74–78°F) until it has risen 50–100%, feels airy, and shows visible bubbles.

- Shape gently and place in banneton for final proof—either at room temp for 2–4 hours or refrigerated overnight (retarded proof).

4. Poor Shaping or Proofing Technique

Even with strong fermentation, poor shaping can cause your loaf to spread out instead of rising upward. Shaping creates surface tension that helps the loaf hold its structure during proofing and baking. A loose or improperly tensioned dough will “pancake” in the proofing basket or on the peel.

Similarly, over-proofing is a silent killer. A dough that has fermented too long loses its ability to expand in the oven. It may look puffy and feel fragile, but once scored and baked, it deflates instead of springing up.

Mini Case Study: Sarah’s Flat Loaf Dilemma

Sarah, a home baker in Portland, followed a popular online recipe for weeks with no success. Her loaves were consistently dense and flat. She assumed her starter was the issue, switching flours and feeding schedules. But after recording her process, she noticed her final proof lasted 5 hours at room temperature—far too long. By switching to a 3-hour proof and improving her shaping technique (tightening the surface tension), her next loaf rose beautifully and had an open crumb. The problem wasn’t her starter—it was over-proofing and weak shaping.

Shaping Tips for Better Rise

- Pre-shape first: Form a loose round and let rest for 20–30 minutes to relax the gluten.

- Create surface tension: Drag the dough across the counter while tucking the edges underneath to tighten the top.

- Seam side up in banneton: Ensures the tight side faces down, helping the loaf rise vertically.

- Use rice flour to prevent sticking: Prevents tearing when turning out.

5. Baking Issues: Lack of Steam or Improper Scoring

Oven spring—the final burst of rise during the first 15 minutes of baking—depends on three things: residual yeast activity, steam, and scoring. If any of these are missing, your loaf won’t expand.

Steam keeps the crust soft initially, allowing the loaf to expand freely. Without it, the crust hardens too soon, restricting rise. Scoring (lame cuts) provides a controlled weak point for expansion. Deep, decisive slashes are better than shallow, hesitant ones.

How to Maximize Oven Spring

- Preheat your Dutch oven for at least 30 minutes—ideally 1 hour—to ensure thermal mass.

- Transfer dough quickly and confidently to minimize heat loss.

- Score with a razor blade or lame at a 30-degree angle, about ½ inch deep.

- Immediately cover and bake: The enclosed pot traps steam naturally.

- After 20 minutes, remove the lid to allow browning and finish baking.

Beginner Sourdough Troubleshooting Checklist

Use this checklist to diagnose and fix common rising issues:

- ✅ Is my starter doubling within 8 hours of feeding?

- ✅ Did I feed it 4–8 hours before mixing the dough?

- ✅ Did I perform at least 4 sets of stretch-and-folds during bulk fermentation?

- ✅ Does my dough pass the windowpane test?

- ✅ Is my kitchen temperature above 70°F (21°C)?

- ✅ Did I monitor dough volume and texture instead of relying solely on time?

- ✅ Did I create surface tension during shaping?

- ✅ Was the final proof no longer than 4 hours at room temp or 12–16 hours in the fridge?

- ✅ Did I preheat my Dutch oven thoroughly?

- ✅ Did I score the loaf deeply and confidently before baking?

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use all-purpose flour instead of bread flour?

Yes, but expect less oven spring and a denser crumb. All-purpose flour has lower protein (around 10–11%) than bread flour (12–14%), so gluten development is weaker. To compensate, reduce hydration slightly and increase folding frequency.

Why does my dough rise fine in the bowl but flatten when I shape it?

This usually means over-fermentation during bulk. The dough has already used up most of its gas-producing energy. When reshaped, it lacks the strength to rebuild structure. Try shortening bulk fermentation by 1–2 hours and check for signs of readiness—volume increase, bubbles, jiggle—not just time.

Should I proof my sourdough in the fridge?

Refrigerated proofing (retardation) is highly recommended for beginners. It slows fermentation, giving you more control, enhances flavor, and makes scoring easier. A cold dough holds its shape better and often produces superior oven spring. Aim for 10–16 hours in the fridge, then bake straight from the refrigerator.

Final Thoughts: Patience and Observation Are Key

Sourdough baking is equal parts science and intuition. There’s no universal timeline—only principles guided by observation. Your dough will tell you when it’s ready: it will jiggle like jelly, feel full of air, and smell pleasantly sour. Trust those cues more than the clock.

Every failed loaf teaches something valuable. Was the starter sluggish? Adjust feeding. Was the dough sticky and collapsed? Shorten fermentation. Did it barely rise in the oven? Check your preheat and scoring. With each bake, you’ll refine your rhythm and develop a deeper understanding of the living dough you’re nurturing.

The journey to a perfectly risen sourdough loaf isn’t about perfection on the first try—it’s about learning to read the dough, adapt to conditions, and build confidence through practice. Keep your starter happy, respect the fermentation window, handle the dough with care, and don’t skip the fundamentals. Soon, that golden, crackling boule with an open crumb will be yours.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?