If you’ve ever listened to a recording of your own voice and thought, “That doesn’t sound like me,” you’re not alone. This reaction is nearly universal—people often cringe or feel confused when they hear their recorded voice for the first time. The truth is, your voice *does* sound different on recordings, but not because the recording is wrong. It’s because of the complex way your brain processes sound during speech. Understanding this phenomenon requires diving into anatomy, physics, and psychology—all of which play a role in shaping your self-perception.

The Dual Pathways of Sound Perception

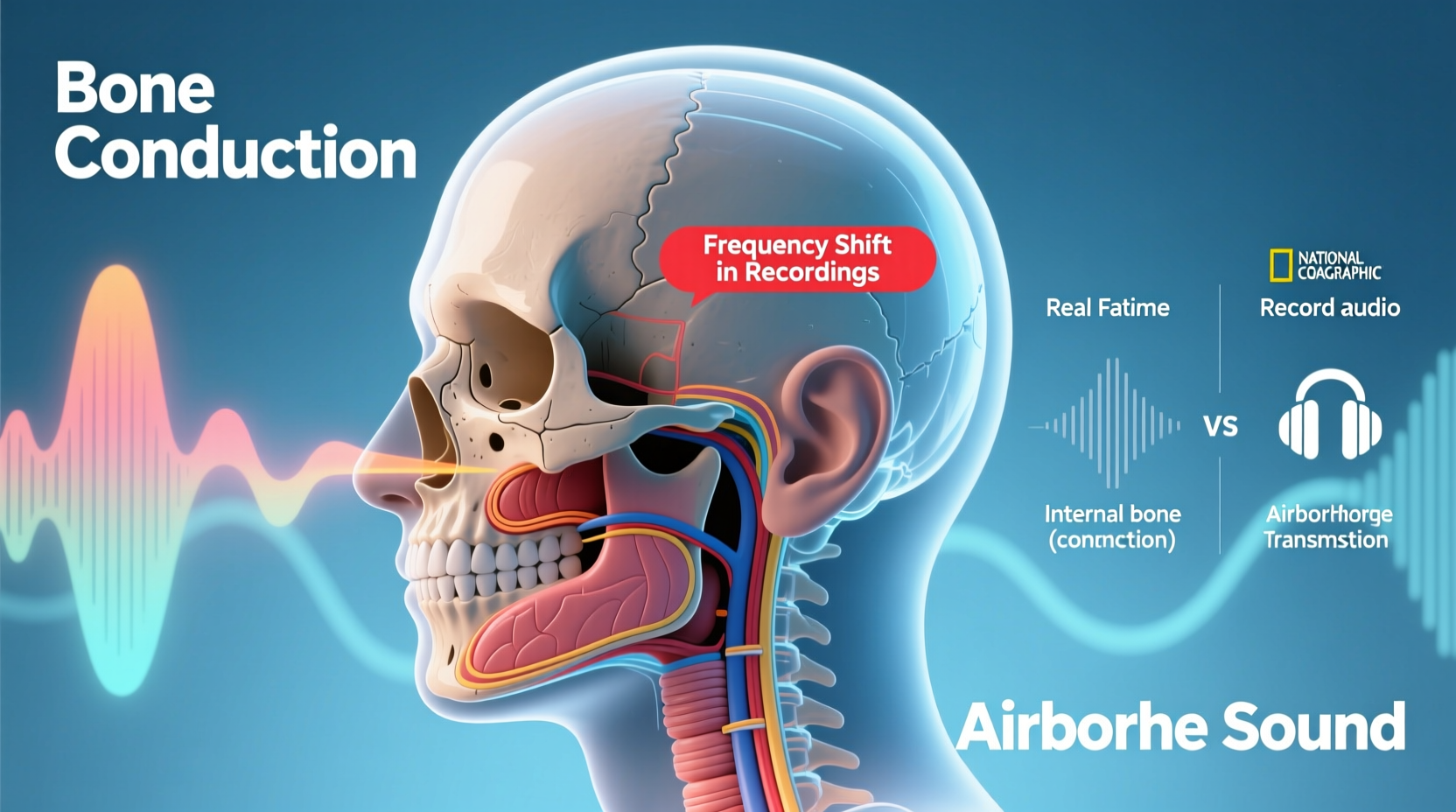

When you speak, your brain receives auditory feedback through two distinct pathways: air conduction and bone conduction. These dual inputs combine to create your internal perception of your voice—a perception that others do not experience.

- Air Conduction: Sound waves travel from your vocal cords through the air, enter your ear canals, vibrate your eardrums, and are processed by your cochlea. This is how everyone else hears your voice—and how microphones capture it.

- Bone Conduction: When you speak, vibrations from your vocal cords also travel through the bones in your skull directly to your inner ear. This pathway emphasizes lower frequencies, making your voice sound deeper and richer to you than it actually is.

This internal resonance is absent in recordings, which only capture the airborne component of your voice. As a result, the version you hear on playback lacks the bassy, full-bodied quality your brain has come to associate with your own speech.

“People don’t recognize their recorded voice because they’re used to hearing it filtered through their skull. The recording reveals the reality.” — Dr. Sidney Shackle, Auditory Neuroscientist

Why Recordings Feel Unfamiliar: The Role of Self-Perception

Your brain forms a mental model of your voice based on years of internal auditory feedback. This model includes the added low-frequency resonance from bone conduction. When a recording contradicts that model, cognitive dissonance occurs—the mismatch between expectation and reality causes discomfort.

Interestingly, studies show that people consistently rate their recorded voices as sounding thinner, higher, and less confident than they believe they sound. But objective analysis often reveals that the recording is more accurate than their internal perception.

This perceptual gap isn’t limited to voice. Similar effects occur with other sensory feedback—like seeing yourself in video versus feeling your movements in real time. The brain relies heavily on internal cues, which don’t always align with external reality.

How Microphones Shape What You Hear

Not all recordings are created equal. The device capturing your voice influences how it sounds:

- Smartphone microphones tend to emphasize mid-to-high frequencies, which can make your voice sound shrill or nasal.

- Professional studio mics are designed for flat frequency response, offering a more balanced and accurate reproduction.

- Compression algorithms in voice messages or video calls (e.g., WhatsApp, Zoom) strip out subtle tonal details, further distorting timbre.

So while the core reason your voice sounds different lies in physiology, the equipment adds another layer of alteration. A poor-quality mic may exaggerate the discrepancy, reinforcing the sense that “this isn’t me.”

The Physics of Voice Production and Transmission

To fully grasp why your voice sounds different, it helps to understand how sound is generated and transmitted.

When you speak, your vocal folds vibrate, producing sound waves. These waves are shaped by your throat, mouth, tongue, and lips into recognizable speech. The resulting sound radiates outward through the air—this is the acoustic signal captured by microphones.

Simultaneously, those same vibrations travel through soft tissues and bone. Bone conducts lower frequencies more efficiently than air, so the skull-borne signal is weighted toward bass tones. Your cochlea receives both signals—airborne and skeletal—but integrates them seamlessly. The final product in your mind is a hybrid voice: part real, part resonant illusion.

Frequency Differences Between Internal and External Hearing

Research using spectral analysis shows measurable differences in perceived pitch and tone:

| Hearing Method | Perceived Pitch | Emphasized Frequencies | Accuracy Compared to Recording |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-hearing (bone + air) | Lower | 60–250 Hz (bass resonance) | Subjectively richer, objectively inaccurate |

| Recording playback | Higher | 250–4000 Hz (speech clarity range) | Objectively accurate, subjectively thin |

| Others hearing you | Matches recording | Air-transmitted spectrum | Same as recording |

This table highlights why the surprise is so common: the voice you know is literally a physically altered version of your actual sound.

Overcoming Discomfort: Practical Strategies

Disliking your recorded voice is normal, but it doesn’t have to be permanent. With practice and exposure, you can recalibrate your self-perception and even develop confidence in your authentic tone.

Step-by-Step Guide to Getting Comfortable with Your Recorded Voice

- Record regularly. Use your phone or laptop to record short monologues daily. Even 30 seconds helps build familiarity.

- Listen in context. Play back recordings while doing neutral activities (e.g., walking, washing dishes) to reduce emotional reactivity.

- Compare objectively. Ask a trusted friend to describe your voice. Their input provides an external benchmark.

- Focus on clarity, not tone. Evaluate articulation, pacing, and expression—qualities that matter more than pitch.

- Use better equipment. Invest in a basic USB microphone to avoid distortion from low-end mics.

- Reframe the experience. Remind yourself that the recording reflects how others hear you—this is valuable self-awareness.

Real-World Example: A Podcast Host’s Journey

Sophie, a marketing professional, decided to launch a podcast to share industry insights. Her first episode took hours to record—she kept stopping to replay sentences, convinced she sounded “annoying” and “too high-pitched.” After listening to the full take, she nearly abandoned the project.

She shared the recording with a colleague who responded, “You sound great—clear, engaging, and professional.” Confused, Sophie asked three more friends for feedback. All confirmed her voice was warm and authoritative.

Determined to improve, she committed to recording five short test clips per week. By week six, she no longer flinched at playback. By month three, she could identify strengths in her delivery—precise diction, natural pacing—that she hadn’t noticed before.

Today, her podcast has thousands of listeners. Looking back, she says, “I wasn’t hearing my voice—I was hearing my insecurity. The recording didn’t change. I did.”

Do’s and Don’ts of Voice Recording and Self-Assessment

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Record in a quiet, carpeted room to reduce echo | Record in tiled bathrooms or empty rooms with hard surfaces |

| Speak at a natural volume, 6 inches from the mic | Shout or whisper directly into the microphone |

| Use headphones to monitor playback instantly | Rely on speaker playback, which introduces delay and distortion |

| Give yourself time to adjust—listen multiple times | Make judgments after one listen, especially immediately after recording |

| Seek constructive feedback from others | Compare your voice to celebrities or public speakers |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is my recorded voice really how others hear me?

Yes—with minor variations based on environment and listening devices. While small distortions can occur due to microphone quality or audio processing, the fundamental tone, pitch, and clarity match what people hear in person.

Can I change my voice to sound better on recordings?

You can improve vocal presence through techniques like diaphragmatic breathing, posture alignment, and articulation exercises. However, trying to artificially deepen your voice often leads to strain. Focus instead on speaking clearly and confidently—the qualities that convey authority and warmth.

Why do some people love their recorded voice while others hate it?

Individual reactions depend on self-image, past experiences with voice evaluation (e.g., singing lessons), and openness to feedback. People with higher self-monitoring tendencies—those who pay close attention to how they appear to others—are more likely to accept their recorded voice sooner.

Final Thoughts: Embracing Your Authentic Sound

Your voice is a unique instrument shaped by biology, habit, and emotion. The discomfort you feel when hearing it recorded isn’t a flaw—it’s a sign that your brain is confronting a hidden truth. The voice you dislike might actually be the one that sounds natural, trustworthy, and human to everyone else.

Instead of resisting the playback, treat it as a tool for growth. Whether you're preparing for presentations, building a personal brand, or simply wanting to communicate more effectively, understanding your real voice is a powerful step toward authenticity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?