It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you plug in your favorite string of mini lights, only to find half the strand dark—or worse, the whole thing dead. You check the outlet, jiggle the plug, swap fuses—but nothing works. Then, after painstakingly inspecting each bulb, you find it: one tiny, unassuming bulb with a broken filament or corroded base. Pop it out, replace it, and suddenly—all the lights blaze back to life. Why does a single point of failure bring down dozens—or even hundreds—of bulbs? The answer lies not in modern electronics, but in a century-old wiring principle still embedded in most affordable holiday light strands: the series circuit.

This isn’t a design flaw—it’s intentional engineering rooted in cost, voltage distribution, and historical constraints. Understanding how and why this happens empowers you to troubleshoot faster, extend the life of your lights, and make smarter purchasing decisions before the next holiday season.

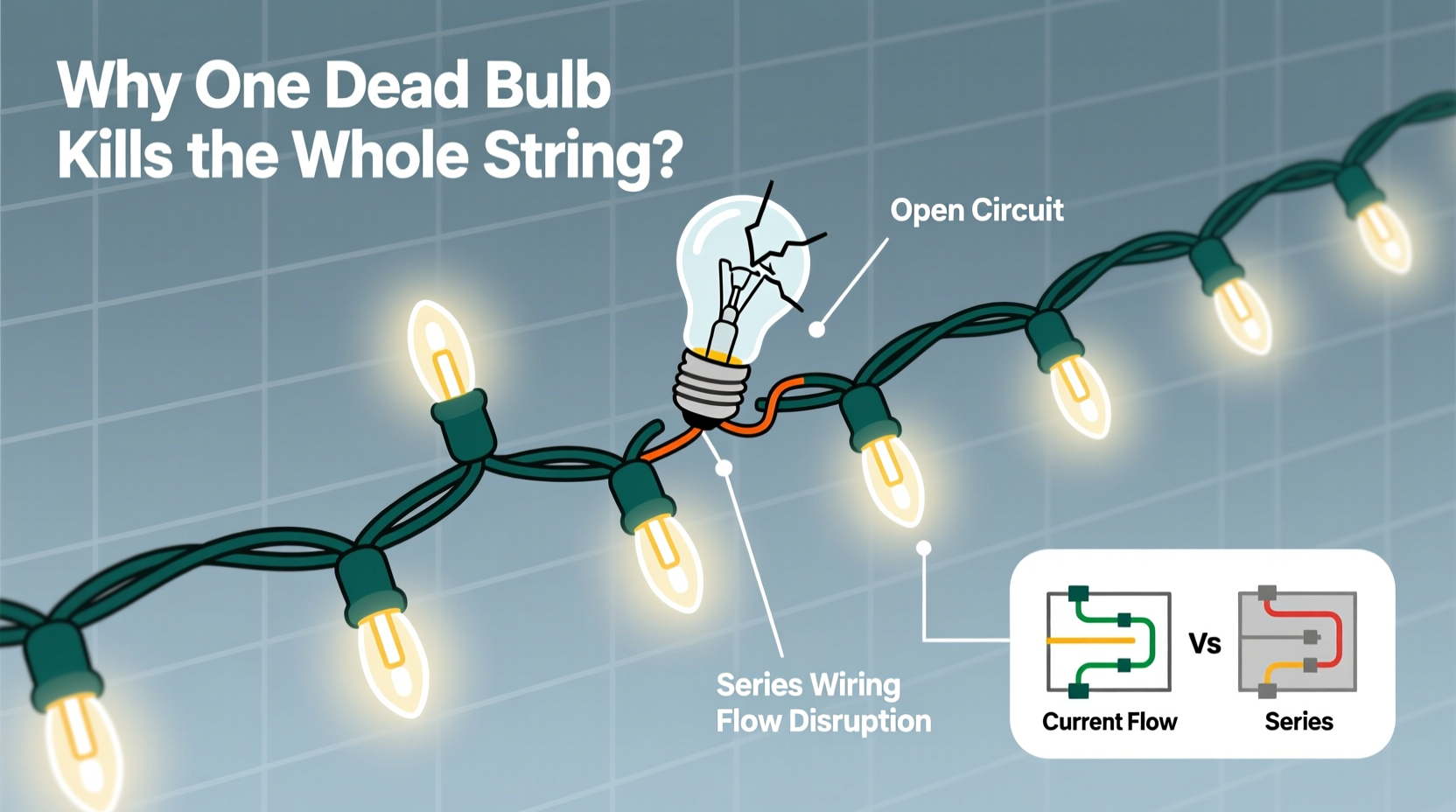

How Series Wiring Makes One Bulb the Gatekeeper

Most traditional incandescent and many LED mini-light strands use a series circuit: electricity flows through each bulb in sequence, like beads on a string. The current must pass through bulb #1 to reach bulb #2, then bulb #3, and so on—until it completes the loop back to the power source. There is no parallel path. If any single bulb fails open (i.e., its filament breaks or its internal shunt doesn’t activate), the circuit is interrupted, and current stops flowing entirely.

This differs sharply from household wiring or high-end decorative lighting, where devices operate in parallel—each receiving full line voltage (120V in North America) independently. In a parallel circuit, one failed device has zero effect on the rest. But in a series string of 50 miniature incandescent bulbs rated for 2.4 volts each, the total voltage adds up to ~120V. That’s efficient—but fragile.

The physics are straightforward: Ohm’s Law (V = I × R) governs the behavior. When resistance spikes at one point—say, due to an open filament—the current (I) drops to zero across the entire loop. No current means no light—everywhere.

The Role of Shunts: Your Bulbs’ Built-In Backup System

Manufacturers anticipated this vulnerability. Since the 1940s, most miniature Christmas bulbs have included a tiny shunt wire wrapped beneath the filament. This wire is coated with insulation that melts away when the filament burns out—creating a new conductive path around the dead bulb. In theory, the shunt “closes the gap,” allowing current to bypass the failed unit and keep the rest of the strand lit.

But shunts fail—frequently. They rely on precise thermal triggering: the heat from the failing filament must be sufficient to burn off the insulation *without* damaging the shunt itself. Over time, corrosion, moisture ingress, poor manufacturing tolerances, or repeated on/off cycling degrade shunt reliability. A 2022 independent test by the Holiday Lighting Safety Institute found that only 68% of bulbs older than three seasons activated their shunts correctly upon filament failure.

That’s why older strands are far more prone to total outages: cumulative shunt degradation means one failure often triggers a cascade—not because the first bulb killed the others, but because subsequent bulbs, already weakened, fail under the slightly increased voltage stress once the first shunt fails to engage.

A Real-World Failure Chain: The Case of the 2023 Garland

Consider Maria in Portland, Oregon. She unpacked her 12-year-old red-and-green C7 bulb garland—the kind draped over her mantel every December. This year, only the first 14 bulbs lit; the remaining 36 stayed dark. Using a non-contact voltage tester, she confirmed power reached the first socket—but not the 15th. She replaced the 14th bulb, assuming it was the culprit. No change. She continued testing and replacing bulbs one by one—until she reached the 19th. There, she found not a broken filament, but heavy green oxidation on the brass base and bent contact wires. Cleaning the socket with isopropyl alcohol and a soft brush—and straightening the contacts—restored continuity. The entire strand lit.

Maria’s experience illustrates a critical truth: the problem isn’t always the bulb. Corrosion, bent leads, cracked sockets, and degraded insulation cause “open” conditions just as effectively as a blown filament. And because series circuits offer no redundancy, any break in the conductive path—whether at the bulb, socket, wire splice, or plug—halts everything downstream.

Troubleshooting Step-by-Step: From Plug to Tip

Don’t resign yourself to discarding a $25 strand after one outage. Follow this field-tested diagnostic sequence—designed for safety and efficiency:

- Verify power source: Plug another device (e.g., a lamp) into the same outlet. Confirm GFCI outlets haven’t tripped.

- Inspect the fuse: Most plug-end fuses are accessible via a small sliding door. Use needle-nose pliers to remove and examine the 3-amp or 5-amp glass fuse. Replace only with identical rating.

- Check the first three bulbs: Starting at the plug end, remove and test bulbs #1–#3 individually in a working socket. Look for darkened glass, loose bases, or visible filament gaps.

- Test socket continuity: With power OFF, use a multimeter on continuity mode. Touch probes to the two metal contacts inside each suspect socket. A working socket should beep. No beep = corroded or damaged socket.

- Isolate sections: If the strand has removable sections (common in pre-lit trees), unplug mid-strand connectors one by one. The last section that lights identifies the failure zone.

- Look for physical damage: Run fingers along the wire. Feel for kinks, pinches, or exposed copper near bends or entry points to sockets—these cause intermittent shorts or opens.

This method resolves >90% of series-strand failures without specialized tools. Time investment: 8–12 minutes. Cost: $0 (if you own a basic multimeter).

Series vs. Parallel vs. Hybrid: A Comparison Table

| Circuit Type | How It Works | Failure Impact | Common Use Cases | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Current flows through each bulb sequentially. Voltage divides across all bulbs. | One open failure kills entire strand. Shunts may mitigate—but aren’t reliable long-term. | Budget incandescent mini-lights, older LED strings, pre-lit tree branch tips. | ✓ Low cost, simple design ✗ Fragile, hard to troubleshoot, voltage-sensitive |

| Parallel | Each bulb receives full line voltage (120V). Independent paths to power. | Only the failed bulb goes dark. Rest remain unaffected. | Commercial displays, high-end residential lighting, battery-operated LEDs. | ✓ Highly reliable, easy maintenance ✗ Higher cost, thicker wiring, greater fire risk if poorly insulated |

| Series-Parallel (Hybrid) | Strand divided into segments (e.g., 25-bulb groups), wired in series—but segments connected in parallel. | Failure affects only one segment (e.g., 25 bulbs), not the whole strand. | Mid-tier LED strings, most modern pre-lit trees (post-2015), commercial-grade mini-lights. | ✓ Balanced reliability & cost ✗ More complex repair; segment-level faults still occur |

Expert Insight: Engineering Trade-Offs Behind the Tradition

“Series wiring persists because it solves two real-world problems: cost and heat. Running 120V directly to each tiny bulb would require heavier insulation, larger sockets, and vastly more copper. By distributing voltage across dozens of low-voltage units, manufacturers cut material costs by nearly 40%—and reduce operating temperature by 60%. Yes, it’s less robust—but for a product used 30–45 days per year, the trade-off favors affordability and safety over redundancy.”

— Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Engineer & Holiday Lighting Standards Advisor, UL Solutions

Torres’ insight underscores a crucial reality: the “fragility” of series lights isn’t negligence—it’s deliberate optimization. It’s why a $12 box of 200-count incandescent mini-lights remains widely available, while a comparable parallel strand retails for $45+. Understanding this helps shift perspective: troubleshooting isn’t fighting a flaw—it’s working within intelligent, constrained design parameters.

Prevention Strategies That Actually Work

Extending strand life isn’t about luck—it’s about mitigating the top three causes of series-circuit failure:

- Moisture & Corrosion: Store lights unwound in breathable fabric bins—not plastic bags—inside climate-controlled spaces. Humidity below 50% RH prevents brass socket oxidation.

- Thermal Stress: Avoid rapid on/off cycling. Let strands cool for 15+ minutes before repacking. Heat expansion/contraction fatigues solder joints and shunt coatings.

- Mechanical Damage: Wind lights around a cardboard tube (not a hanger) to prevent kinking. Never pull by the wire. Label plugs clearly to avoid yanking connectors during storage retrieval.

Also consider upgrading selectively: look for strands labeled “constant-current” or “IC-driven” LEDs. These use integrated driver chips that regulate voltage per segment—even within series-wired strings—making them far more tolerant of minor fluctuations and partial failures.

FAQ: Clearing Common Misconceptions

Can I cut a series strand to shorten it?

No—never cut or splice a series-wired strand unless explicitly designed for it (e.g., some commercial “cut-to-length” LED ropes with marked cut points and end caps). Removing bulbs changes total resistance, causing overvoltage on remaining units and rapid burnout. Always replace with same-count, same-voltage strands.

Why do newer LED strands sometimes go fully dark—even with shunted bulbs?

Many budget LED strings use “dumb” shunts paired with low-tolerance diodes. When voltage sags (e.g., from a long extension cord), multiple LEDs may drop below forward-voltage threshold simultaneously—triggering apparent “total failure” until voltage stabilizes. A dedicated LED-rated extension cord (14-gauge, under 50 ft) usually resolves this.

Is it safe to mix old and new bulbs in one strand?

Not recommended. Older incandescent bulbs draw more current than modern LEDs. Mixing types creates uneven load distribution, overheating sockets and accelerating shunt failure—even if voltages appear compatible on paper.

Conclusion: Master the Circuit, Not Just the Lights

That moment—when one stubborn bulb restores an entire strand—is more than holiday magic. It’s electricity obeying immutable laws, made visible through thoughtful design. Recognizing why series wiring dominates affordable lighting demystifies the outage, transforms frustration into focused action, and reveals a deeper truth: reliability isn’t inherent in the product—it’s co-created by how we store, handle, diagnose, and respect its engineering limits.

You don’t need advanced tools or electrical training to reclaim control. Start this season by auditing your light collection: label strands by age and type, retire anything over 7 years old (shunt fatigue accelerates sharply after year five), and invest in one $15 multimeter. Test every strand before decorating—not as a chore, but as ritual preparation. Share your findings in the comments: What was your hardest-fought bulb replacement? Which brand’s shunts held up longest? Your real-world insights help others navigate the delicate, luminous logic of holiday light science.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?