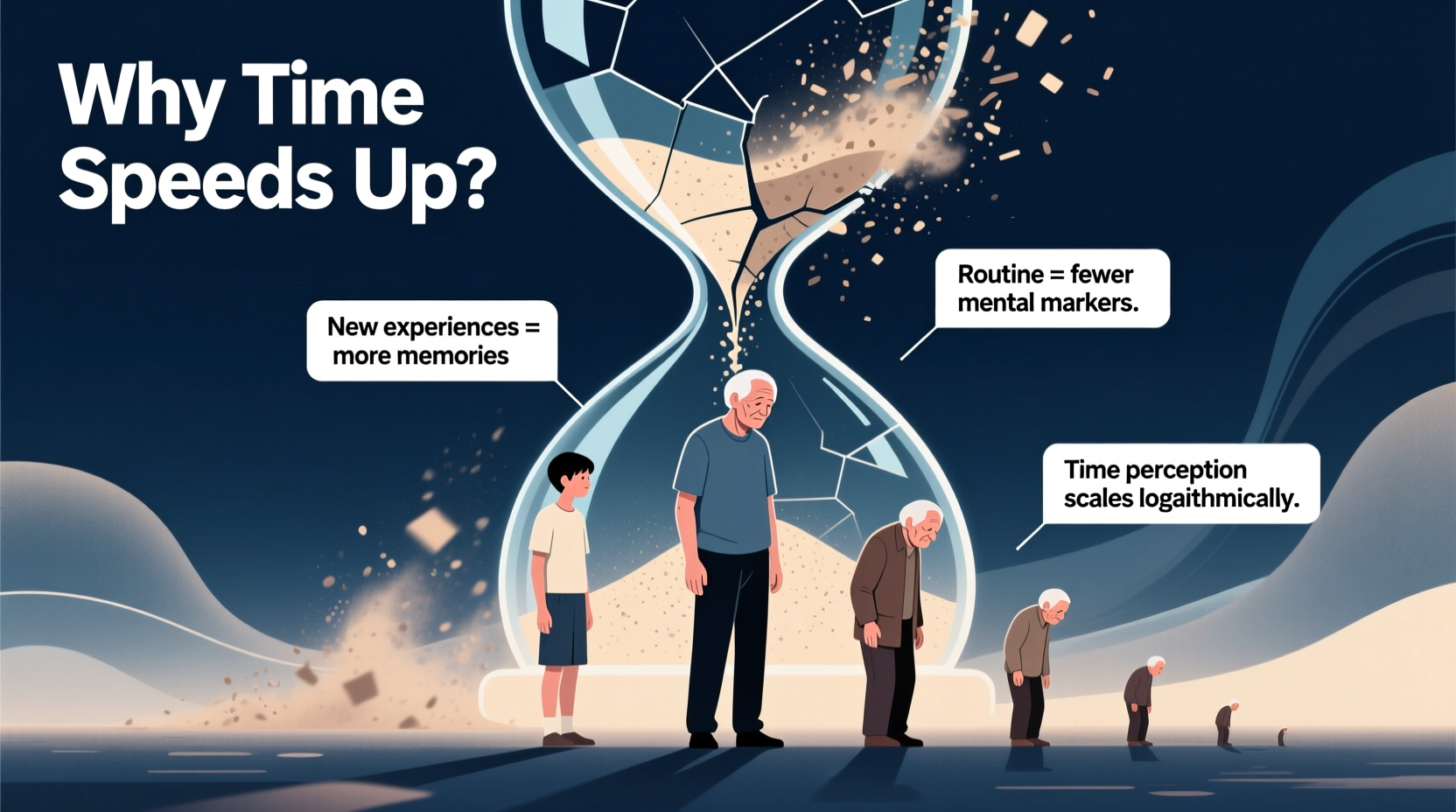

Most people reach a point in their lives when they realize that years seem to pass faster than they used to. Where did summer go? How is it December already? This sensation—that time accelerates with age—is nearly universal, yet it defies logic. Time itself doesn’t change; clocks tick at the same rate whether you’re five or fifty. So why does it feel so different? The answer lies not in physics, but in psychology, neuroscience, and the way our brains process memory and novelty.

This phenomenon isn’t just anecdotal. Psychologists and neuroscientists have studied it for decades, identifying key cognitive mechanisms that make childhood summers feel endless while adult decades blur into one another. Understanding these patterns doesn’t reverse aging, but it can help us reclaim a sense of presence and intentionality in how we experience time.

The Proportional Theory: A Mathematical View of Time

One of the oldest explanations for why time feels faster as we age comes from 19th-century philosopher Paul Janet. His idea, now known as the “proportionality theory,” suggests that each passing year represents a smaller fraction of your total life.

Consider this: When you're five years old, one year is 20% of your entire existence. That’s a massive slice of lived experience. By contrast, when you're 50, one year is just 2% of your life. The relative weight of that year diminishes significantly. Because each new year becomes a smaller proportion of your overall timeline, it feels subjectively shorter.

This theory aligns with how humans perceive many stimuli—not by absolute value, but by comparison. Just as a $10 bill feels more substantial to a child than to an adult, a single year carries less emotional and experiential weight later in life.

Memory Density and Novelty: Why Childhood Feels Longer

If proportionality explains part of the puzzle, memory formation explains much more. Our perception of time is deeply tied to how many new experiences we encode. When we encounter novel events, our brains work harder to store them, creating rich, detailed memories. These dense clusters of recollection make a period feel longer in retrospect.

Childhood and adolescence are filled with “firsts”—first day of school, first bike ride, first kiss. Each event stands out because it breaks routine. As adults, however, life stabilizes. Work schedules, commutes, and familiar social circles create predictable loops. Fewer unique moments mean fewer strong memories, leading to the feeling that months or even years vanish without a trace.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman explains:

“The brain encodes new experiences more richly than routine ones. When you look back, periods packed with novelty seem longer because they contain more memory landmarks.”

This is why a two-week vacation in a foreign country—full of new sights, sounds, and challenges—can feel like it lasted months, while a typical work month blurs into sameness.

The Role of Routine and Cognitive Efficiency

As we age, our brains become highly efficient at processing daily tasks. We don’t need to concentrate hard on brushing our teeth, driving to work, or making coffee. This efficiency is beneficial—it frees up mental resources—but it comes at a cost: reduced attention leads to weaker memory encoding.

When you perform actions on autopilot, your brain doesn’t register them as significant events. Over time, these unmemorable days stack up, creating what psychologists call “temporal compression.” You don’t remember last Tuesday because nothing about it stood out.

In contrast, children operate in a constant state of learning. Everything requires focus. Learning to tie shoes, read a clock, or navigate social rules—all demand full attention. This heightened awareness results in more vivid, lasting memories, which makes early life feel expansive in hindsight.

| Life Stage | Typical Experience Load | Memory Density | Perceived Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood (0–12) | High novelty, frequent firsts | Very high | Feels long |

| Adolescence (13–19) | Many social and physical changes | High | Feels extended |

| Young Adulthood (20–35) | Moderate novelty (career, relationships) | Moderate | Begins to accelerate |

| Middle Age (36–60) | Routine-heavy, fewer firsts | Low | Speeds up noticeably |

| Later Life (60+) | Varies; often reflective or structured | Depends on engagement | Can feel fast or slow |

How to Slow Down Your Perception of Time

You can’t stop aging, but you can influence how time *feels*. By intentionally increasing novelty, breaking routines, and deepening attention, you can create richer memories and stretch your subjective experience of time.

Step-by-Step Guide to Making Time Feel Slower

- Seek New Experiences Regularly

Try a new restaurant, take a different route to work, attend a workshop. Even small changes introduce novelty. - Learn a Skill

Take up painting, learn a language, or play an instrument. The effort involved creates strong memory traces. - Travel Mindfully

When traveling, avoid over-scheduling. Focus on sensory details—smells, textures, sounds—to deepen imprinting. - Practice Mindfulness or Meditation

These techniques train your brain to stay present, reducing autopilot mode and enhancing moment-to-moment awareness. - Keep a Journal

Writing about your days forces reflection and strengthens memory. Even brief nightly notes help preserve the texture of time. - Break Routines Every Week

Eat breakfast in a new place, switch your workout, or rearrange your furniture. Disruption signals the brain that something different is happening.

Real Example: Mark’s Midlife Shift

Mark, a 47-year-old accountant, began noticing that his years were slipping by unnoticed. Birthdays came and went, holidays blended together, and he couldn’t recall what he’d done the previous summer. Concerned, he started experimenting with intentional novelty.

He joined a weekend hiking group, began learning Spanish through an app, and committed to visiting one new city each quarter. He also started a simple journal, writing three sentences each night about his day.

Within six months, Mark reported a dramatic shift. “It’s not that time slowed down literally,” he said, “but I feel like I’m actually living it. I can remember specific moments from March, which never happened before. It’s like my life has more texture.”

His experience illustrates a core truth: time perception is malleable. When you enrich your experiences, you enrich your memory—and your sense of time expands accordingly.

Expert Insight: What Neuroscience Says

Dr. Sophie Lebrecht, a cognitive psychologist specializing in time perception, emphasizes the role of attention:

“We don’t remember time—we remember what captured our attention. The busier and more routine-driven your life, the fewer attentional anchors you create. That’s why retirement or sabbaticals, despite being slower-paced, often feel longer in retrospect: there’s more space for novelty and reflection.”

She also warns against digital overload: “Scrolling through social media is the ultimate time thief. It’s repetitive, passive, and leaves almost no memory trace. You’ll struggle to recall anything from those hours, making weeks feel like they vanished.”

Checklist: Build a Time-Slowing Lifestyle

- ✅ Introduce one new activity per month

- ✅ Practice mindfulness for 5–10 minutes daily

- ✅ Keep a weekly log of memorable moments

- ✅ Limit passive screen time, especially mindless scrolling

- ✅ Plan micro-adventures (e.g., explore a new neighborhood)

- ✅ Reflect on your day before bed—what stood out?

- ✅ Say “yes” to invitations that push you slightly outside your comfort zone

Frequently Asked Questions

Does everyone feel like time speeds up with age?

While not universal, the vast majority of adults report this sensation. Cultural factors, lifestyle, and personality influence the degree, but the underlying cognitive mechanisms—reduced novelty and memory density—affect most people as they age.

Can trauma or major life events distort time perception?

Yes. Traumatic or highly emotional events often create exceptionally vivid memories, making those periods feel longer in retrospect. Conversely, prolonged stress or depression can lead to memory gaps, causing time to feel like it “skipped” or passed in a blur.

Is there a biological reason time feels faster?

Some researchers suggest metabolic rate may play a minor role—children’s faster heart rates and breathing might contribute to a denser internal “clock.” However, psychological factors like memory and attention are considered far more influential than any physiological ticking.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Your Relationship with Time

The feeling that time accelerates with age isn’t a flaw—it’s a side effect of growing up, settling into patterns, and mastering life’s routines. But that doesn’t mean we have to accept it passively. By understanding the psychology behind time perception, we gain power over it.

You don’t need grand gestures to make time feel fuller. Small, consistent choices—trying something new, paying attention, reflecting on your days—can dramatically alter how you experience the passage of time. Instead of looking back and wondering where the years went, you can build a life rich with moments worth remembering.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?