It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you’re hanging lights, notice one dim or dead bulb, pull it out—and suddenly the entire string goes dark. No flicker, no warning—just silence and darkness across dozens or even hundreds of bulbs. This isn’t faulty wiring or a blown fuse in your home panel. It’s physics, circuit design, and decades of cost-driven engineering working exactly as intended—just not in the way most people expect. Understanding why this happens demystifies troubleshooting, saves time during seasonal setup, and helps you choose smarter lighting solutions for years to come.

The Series Circuit Principle: Why One Break Stops All Current

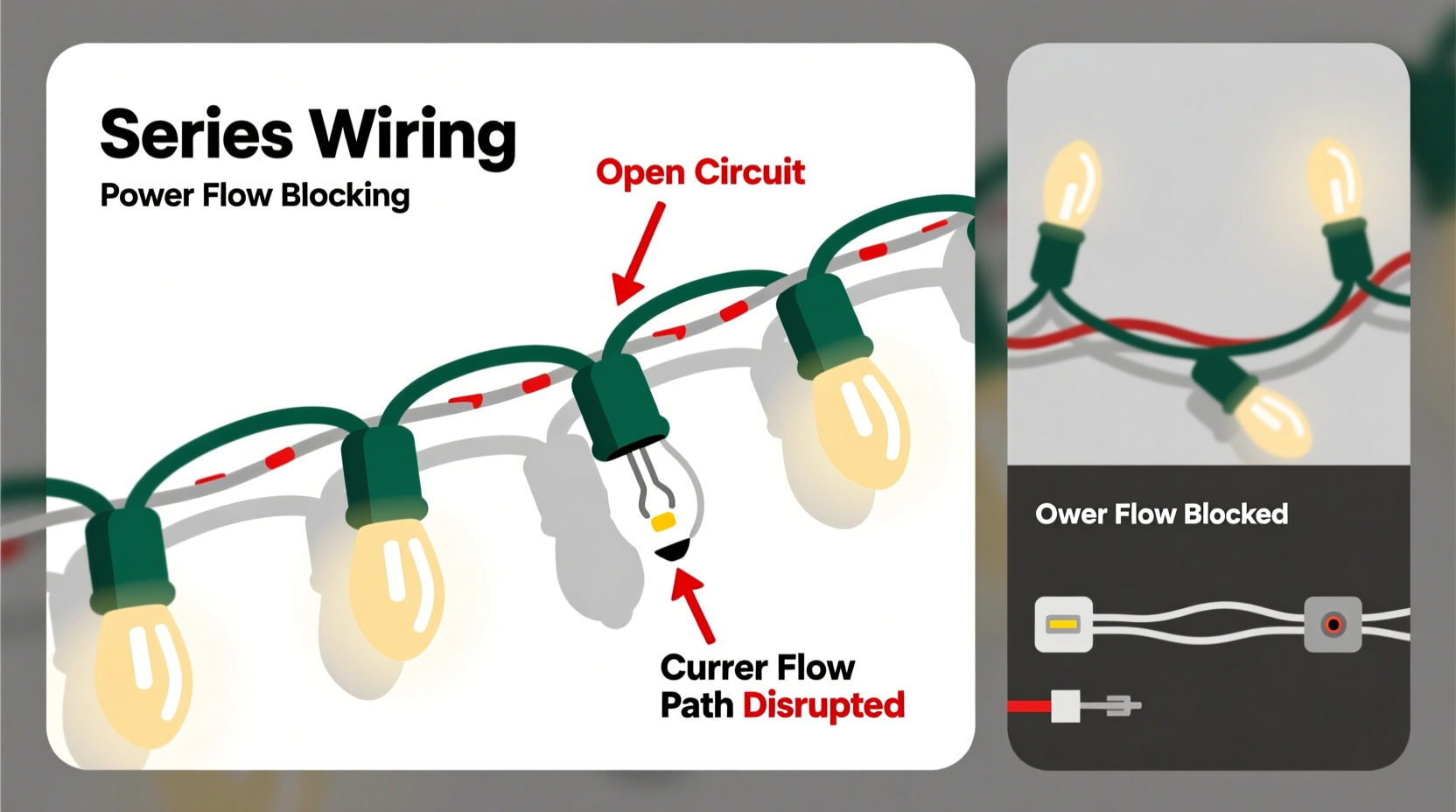

Most traditional incandescent mini-light strings—especially those manufactured before 2015—are wired in a series circuit. In this configuration, electricity flows through each bulb in sequence: from the plug → bulb #1 → bulb #2 → bulb #3 → … → bulb #n → back to the outlet. There are no parallel branches. If any single point in that unbroken loop fails—whether due to a broken filament, loose socket contact, or a physically removed bulb—the path is interrupted, and current stops flowing entirely.

Think of it like a single-lane mountain road with no exits or detours. If one car stalls mid-passage, every vehicle behind it halts—not because they’ve broken down, but because forward movement is physically impossible. That’s precisely how series-wired lights behave. A missing bulb creates an open circuit: infinite resistance where continuity should exist.

This design wasn’t chosen for user convenience—it was selected for affordability and simplicity. Series wiring uses thinner gauge wire, requires fewer copper connections, and eliminates the need for individual bulb shunts (more on those shortly). For mass-produced, low-cost seasonal decor, it remains economically compelling—even if it frustrates users every December.

Shunts: The Hidden Safety Mechanism (and Why They Sometimes Fail)

Here’s where things get nuanced: many modern mini-light strings *do* include built-in bypass devices called shunts. These are tiny, coiled wires wrapped around the bulb’s filament supports inside the base. When a filament burns out, the resulting surge in voltage across the dead bulb heats the shunt’s insulation, causing it to melt and short-circuit—effectively creating a new conductive path *around* the failed bulb. With a functioning shunt, the rest of the string stays lit.

But shunts aren’t foolproof. They require precise voltage conditions to activate. If a bulb is simply unplugged—or twisted too loosely in its socket—the shunt never engages. There’s no voltage surge, no heating, no bypass. The circuit remains open. Similarly, shunts degrade over time: repeated thermal cycling, moisture exposure, or manufacturing inconsistencies can render them inert. Studies by the UL (Underwriters Laboratories) show shunt failure rates climb to 18–22% in strings older than three seasons.

“Shunts are elegant in theory but fragile in practice. Their reliability drops significantly after the first season of outdoor use—especially when lights are stored compressed or exposed to temperature swings.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Safety Engineer, UL Solutions

Why “Unplugging One Strand” Is Especially Disruptive

The phrase “unplugging one strand” often misleads. What most people describe as “unplugging” is actually disconnecting a section at its male/female connector—common in multi-string setups where several 50- or 100-light segments daisy-chain together. These connectors aren’t just physical couplings; they’re critical electrical junctions.

In daisy-chained systems, power doesn’t flow independently through each segment. Instead, it travels downstream: the first string receives full line voltage (120V in North America), then passes *reduced* voltage to the second string via its internal wiring—and so on. Each subsequent string is designed to operate only within a narrow voltage window. Remove one segment, and you break the engineered load balance. The remaining strings may receive excessive voltage (risking immediate burnout) or insufficient voltage (causing dimming or total shutdown). Worse, some controllers or fuses in the first plug detect the sudden change in current draw and trip as a safety measure.

This cascading failure explains why pulling a middle strand—say, the third of five—can kill everything downstream *and* sometimes trigger protective cutoffs upstream. It’s not just interruption; it’s system-level destabilization.

How to Diagnose & Fix the Problem (Without Guesswork)

When your lights go dark after removing a bulb or segment, follow this step-by-step diagnostic protocol—designed to isolate cause, avoid damage, and restore function efficiently:

- Verify outlet and circuit breaker: Plug in a known-working device (e.g., phone charger) to rule out household power issues.

- Inspect the plug and fuse: Many light strings have a small, slide-out fuse compartment near the male plug. Check for a blown glass fuse (look for a broken filament inside) and replace it with the exact amperage rating (usually 3A or 5A).

- Test continuity at the first bulb socket: Using a multimeter set to continuity mode, touch probes to the two metal contacts inside the first socket (with bulbs removed). You should hear a beep. If not, the wire between plug and first socket is broken—a common failure point in older strings.

- Check for “dead zones”: Starting at the first bulb, insert a known-good bulb into each socket one by one. If the string reignites after inserting a specific bulb, that socket likely has a bent contact or corrosion. If it stays dark until you reach bulb #27, the break is upstream of that point.

- Examine daisy-chain connectors: Look for bent pins, melted plastic, or greenish corrosion on metal contacts. Clean gently with isopropyl alcohol and a cotton swab. Re-seat firmly—many failures stem from poor connection, not component failure.

Comparison: Series vs. Parallel vs. Smart-Wired Strings

Not all light strings behave the same way. Your choice of technology directly determines resilience to single-point failure. This table compares core architectures used in consumer-grade holiday lighting:

| Wiring Type | Failure Behavior | Typical Use Cases | Lifespan Expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Series (no shunts) | One dead/missing bulb kills entire string | Budget incandescent strings ($3–$8); pre-2010 vintage | 1–2 seasons (indoor), <1 season (outdoor) |

| Series with Shunts | Dead filament usually bypassed; unplugged bulb still breaks circuit | Mid-tier incandescent & LED mini-lights ($8–$20) | 3–5 seasons with careful storage |

| True Parallel Wiring | Each bulb operates independently; one failure has zero effect | Premium commercial LED strings, architectural lighting, battery-operated sets | 7–10+ seasons |

| Smart-IC Controlled (LED) | Individual bulb control; failures isolated; often auto-diagnose via app | Wi-Fi-enabled LED strings (e.g., Philips Hue, Nanoleaf) | 5–8 seasons; firmware updates extend functionality |

Real-World Case Study: The Thompson Family’s Tree Night

Last December, the Thompsons purchased a 300-light LED string marketed as “shunt-protected” and “easy to maintain.” While decorating their 7-foot Fraser fir, their youngest child accidentally yanked bulb #87 from its socket. The entire string went dark. Frustrated, they replaced the bulb—but nothing changed. They checked the fuse (intact), tried a different outlet (same result), and even swapped in a spare bulb from another brand (still dark).

What they didn’t realize: the “shunt-protected” claim applied only to *filament burnout*, not mechanical removal. Their string used a hybrid design—series wiring with shunts activated only when voltage spiked across a burnt-out filament. A pulled bulb created an open circuit without triggering the shunt. Further investigation revealed bent contacts in socket #87, preventing proper reseating. After gently prying the contacts upward with needle-nose pliers and reinserting the bulb, the string lit fully.

This scenario underscores two critical lessons: marketing claims about “self-healing” lights rarely cover human handling errors, and physical socket integrity matters as much as electronic design.

Prevention Strategies That Actually Work

Instead of reacting to failures, adopt these proven habits to minimize disruption and extend string life:

- Test before decorating: Plug in each string for 15 minutes before mounting. Heat expansion reveals intermittent connections and weak shunts.

- Store coiled—not knotted: Wind lights around a flat cardboard spool or dedicated storage reel. Tight knots stress wire insulation and strain solder joints.

- Label connectors: Use masking tape and a marker to label “A,” “B,” “C” on daisy-chain ends. Reconnecting mismatched segments can overload circuits.

- Use a bulb tester: A $5 handheld tester (with battery-powered probe) identifies dead bulbs and open sockets in seconds—no guesswork or multimeter required.

- Upgrade selectively: Replace only high-failure strings (e.g., outdoor roof lines) with true parallel or smart-IC models. Keep simpler series strings for indoor, low-risk applications like mantle displays.

FAQ: Common Questions About Light String Failures

Can I repair a broken wire inside the string?

Yes—but only if you have soldering experience and can access the break point. Most failures occur near sockets or plugs, where flexing causes wire fatigue. Cut out the damaged section, strip insulation, twist wires, solder, and seal with heat-shrink tubing. Avoid electrical tape: it degrades under heat and UV exposure. For most consumers, replacement is safer and more reliable.

Why do some new LED strings still go dark when one bulb is removed?

Many budget LED strings use series architecture for cost reasons—even though LEDs consume less power. They rely on constant-current drivers, not voltage division, but still require a complete loop for operation. Removing a bulb breaks that loop. True parallel or individually addressable LEDs are significantly more expensive to manufacture, so economy models retain legacy design logic.

Is it safe to leave lights plugged in overnight?

Modern UL-listed strings with intact fuses and undamaged cords are generally safe for overnight use—provided they’re rated for indoor/outdoor use as needed, not covered by flammable materials (like dried pine boughs), and not overloaded on a single outlet. However, always unplug before sleeping if using older strings (pre-2010), frayed cords, or non-UL-certified imports. Heat buildup in compromised wiring remains the leading cause of holiday electrical fires.

Conclusion: Turn Frustration Into Informed Control

That moment of darkness—when one bulb’s absence plunges your entire display into silence—isn’t magic, malice, or manufacturing sabotage. It’s the visible consequence of deliberate engineering trade-offs: lower cost, simpler production, and compact design—all prioritized over user resilience. But understanding the “why” transforms helplessness into agency. You now know how series circuits behave, when shunts engage (and when they don’t), why daisy-chain connectors are mission-critical, and how to distinguish between a $2 bulb issue and a $20 wiring failure. You can diagnose faster, repair smarter, and shop more intentionally—choosing strings aligned with your tolerance for troubleshooting and your commitment to longevity.

This holiday season, don’t just hang lights. Hang knowledge alongside them. Test early, store thoughtfully, inspect connectors, and invest in parallel or smart-wired strings where reliability matters most. Your future self—standing barefoot on cold tile at 10 p.m. on December 23rd, holding a multimeter and a bag of spare bulbs—will thank you.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?