It’s a moment every event technician, retail display manager, or holiday decorator has dreaded: you gently unplug a single string of LED lights from a 50-foot daisy-chained run—and suddenly, 37 other strands go dark. No fuse blows. No breaker trips. Just silence—and a cascade of frustrated customers, delayed installations, or failed photo shoots. This isn’t a glitch. It’s fundamental physics meeting flawed topology. Understanding why unplugging one strand kills the entire chain isn’t just about troubleshooting—it’s about preventing safety hazards, avoiding costly downtime, and designing displays that perform reliably under real-world conditions.

The Physics Behind the Failure: Series vs. Parallel Realities

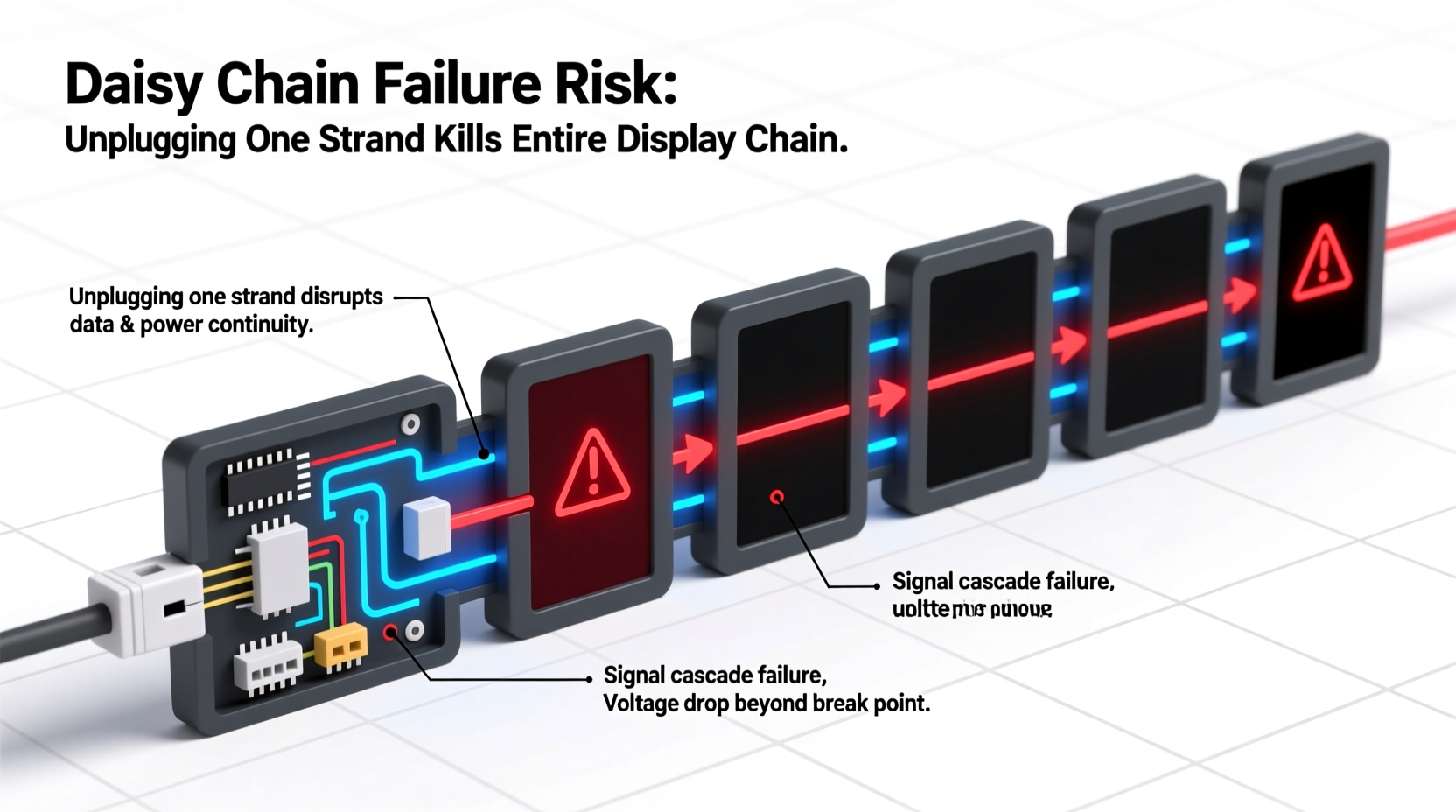

Daisy chaining is often misunderstood as a simple “plug-and-play” extension method—but electrically, most consumer-grade LED light strings (especially those marketed for retail, architectural accents, or seasonal displays) are wired in *series-parallel hybrids*, not true parallel circuits. In a pure series circuit, current flows through each component sequentially: if one bulb burns out or a connection opens, the circuit breaks entirely. While modern LEDs rarely fail open-circuit due to built-in shunt resistors, the *power delivery path* between strands remains vulnerable.

Most low-voltage (e.g., 24V DC or 12V DC) LED strips and strings use a “pass-through” connector design: power enters the first strand, powers its LEDs, then exits via a second set of terminals to feed the next strand. That exit point is not redundant—it’s the *only* path forward. If that connection is physically severed (by unplugging), the downstream voltage drops to zero instantly. There is no alternate routing, no automatic bypass, and no intelligent load balancing. The result? A single point of failure propagates unimpeded.

This differs sharply from enterprise-grade architectural lighting systems, where controllers use distributed power supplies, looped topologies, or DMX-controlled zones with isolated outputs. Consumer daisy chains prioritize cost and simplicity over resilience—making them inherently fragile.

Three Hidden Dangers Beyond the Blackout

When one strand fails and takes down the chain, the visible symptom is darkness—but the underlying risks run deeper:

- Voltage Stress on Remaining Strands: When a downstream segment disconnects, the upstream power supply may attempt to compensate by increasing output voltage or current momentarily—especially with poorly regulated wall adapters. This transient surge can overstress the last active strand’s driver ICs, accelerating thermal degradation.

- Thermal Runaway in Partial Chains: If only part of a long chain remains powered (e.g., due to a faulty middle connector), the remaining segments may draw higher current per meter to maintain brightness—causing localized overheating. UL-listed LED strings are rated for full-chain operation; partial loads violate thermal design assumptions.

- Ground-Fault and Shock Risk: Daisy chains often use two-conductor wiring without dedicated grounding. When connectors are repeatedly plugged/unplugged while live (a common field practice), micro-arcing degrades contacts, increasing resistance and potential for leakage current. In damp environments—like outdoor retail displays or warehouse loading docks—this raises electrocution risk, especially when metal mounting hardware is involved.

Real-World Failure: The Mall Holiday Display Incident

In November 2023, a major U.S. regional mall deployed a 240-foot animated LED curtain across its central atrium. The installation used 24 identical 10-foot strands daisy-chained from a single 120W 24V switching power supply. On opening night, a maintenance worker unplugged the 17th strand to replace a damaged section—unaware it was mid-chain. Instantly, all 17 downstream strands went dark. Worse: the upstream 6 strands began emitting a high-pitched whine and visibly dimmed over 90 seconds before failing completely.

Investigation revealed the power supply had entered overvoltage protection mode, then attempted recovery by cycling output—sending repeated 32V spikes to the first six strands. Three driver boards were destroyed, and two strands showed melted solder joints near their input terminals. The mall incurred $4,200 in replacement parts and lost 38 hours of prime holiday foot traffic. Crucially, the manufacturer’s spec sheet never mentioned “single-point failure propagation”—only “up to 24 strands supported.” The danger wasn’t in the number—it was in the topology.

How to Build Resilient Displays: A Step-by-Step Design Guide

Robustness isn’t optional in commercial or public-facing lighting. Follow this sequence to eliminate daisy-chain fragility:

- Calculate Total Load Per Segment: Divide your total string length into logical zones (e.g., 5–8 strands). Use a multimeter to measure actual current draw per strand—not just the label rating. Add 20% headroom.

- Select Power Supplies with Independent Outputs: Replace single-output adapters with multi-rail supplies (e.g., Mean Well HLG-120H-24 with dual 24V outputs) or use one supply per zone, each feeding its own starting point.

- Implement Star Wiring (Not Daisy): Run individual 18 AWG copper wires from each power supply output directly to the *first* connector of each zone. Avoid chaining outputs. Label all wires at both ends.

- Add Inline Fusing Per Zone: Install 2A fast-blow fuses (e.g., Littelfuse 0451002.MR) on the positive line of each zone. This contains faults and prevents cascading damage.

- Verify Ground Continuity: Use a continuity tester to confirm all metal housings, mounting rails, and power supply chassis share a common ground path back to the service panel—not just floating through daisy-chain shields.

| Design Approach | Failure Propagation Risk | Installation Time | Long-Term Maintenance Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daisy Chain (Standard) | Extreme — 100% cascade likely | Lowest | Highest (repeated replacements, labor) |

| Star-Wired Zones | Negligible — faults isolated to single zone | Moderate (+25%) | Lowest (targeted repairs, no chain-wide diagnostics) |

| Looped Redundant Feed | None — auto-failover if one path breaks | High (+60%) | Moderate (requires specialized controllers) |

Expert Insight: What Engineers Wish You Knew

“The biggest misconception is that ‘daisy chain’ implies scalability. It doesn’t. It implies dependency. Every time you add a link, you multiply the probability of an open-circuit fault—and in low-voltage DC systems, that’s almost always the dominant failure mode. If your application requires uptime, treat daisy chaining like using duct tape to hold together a suspension bridge: it works until it doesn’t—and then the consequences scale with length.”

— Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Systems Architect, Lumina Labs & IEEE Senior Member

“UL 2388 and IEC 62368-1 now require failure-mode analysis for any lighting product sold commercially. Yet most off-the-shelf daisy-chainable strings carry only basic component-level certifications—not system-level validation. That gap is where real-world failures happen.”

— Marcus Chen, Compliance Director, Lighting Safety Institute

FAQ: Critical Questions Answered

Can I fix a broken daisy chain by adding a jumper wire?

No—unless you fully understand the internal wiring topology. Most strands use separate +V and GND pass-through paths. A simple jumper may short the circuit or bypass critical current-limiting components. Instead, replace the faulty connector assembly or rewire using a certified inline splice kit (e.g., Wiremold LED-SPLICE-24V).

Why don’t manufacturers build in automatic bypasses?

They do—in high-end products. But bypass circuitry (like active MOSFET switches or opto-isolated relays) adds $3–$7 per strand. At scale, that kills margins for mass-market lighting. Budget strings rely on passive shunts, which only work across individual LEDs—not between strands.

Is there any safe way to daisy chain for temporary setups?

Yes—if you limit runs to ≤5 strands, use only UL-listed power supplies rated for *continuous* duty at 80% of max load, and install a master switch that cuts power before any physical disconnection. Never exceed the manufacturer’s stated “maximum daisy-chain length” — and halve it for outdoor or high-vibration environments.

Conclusion: Stop Chaining—Start Zoning

The phrase “unplugging one strand kills the whole display” isn’t a warning—it’s a diagnostic clue pointing to systemic vulnerability. Daisy chaining persists because it’s convenient, inexpensive, and familiar—not because it’s sound engineering. Every blackout, every burnt-out driver, every near-miss with stray voltage traces back to that single point of dependency. Moving to zoned, star-wired architectures demands upfront planning, but it pays dividends in reliability, safety, and operational confidence. Your displays shouldn’t be held hostage by a single connector. Audit your next installation not for how many strands you can link—but for how gracefully each segment can operate in isolation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?