Liquor stays liquid even when stored in a home freezer. Unlike water, which solidifies at 0°C (32°F), alcoholic beverages rarely turn to ice under typical freezing conditions. This common observation raises an important scientific question: why doesn’t alcohol freeze easily? The answer lies in the chemistry of ethanol, freezing point depression, and molecular interactions between alcohol and water. Understanding this phenomenon not only satisfies curiosity but also has practical applications—from cocktail preparation to industrial fluid design.

The Science of Freezing Points

Freezing occurs when a liquid transitions into a solid state due to reduced thermal energy. For pure substances like water, this happens at a specific temperature—0°C—where molecules slow down enough to form a stable crystalline lattice. However, when different substances are mixed, such as ethanol and water, their combined behavior changes dramatically.

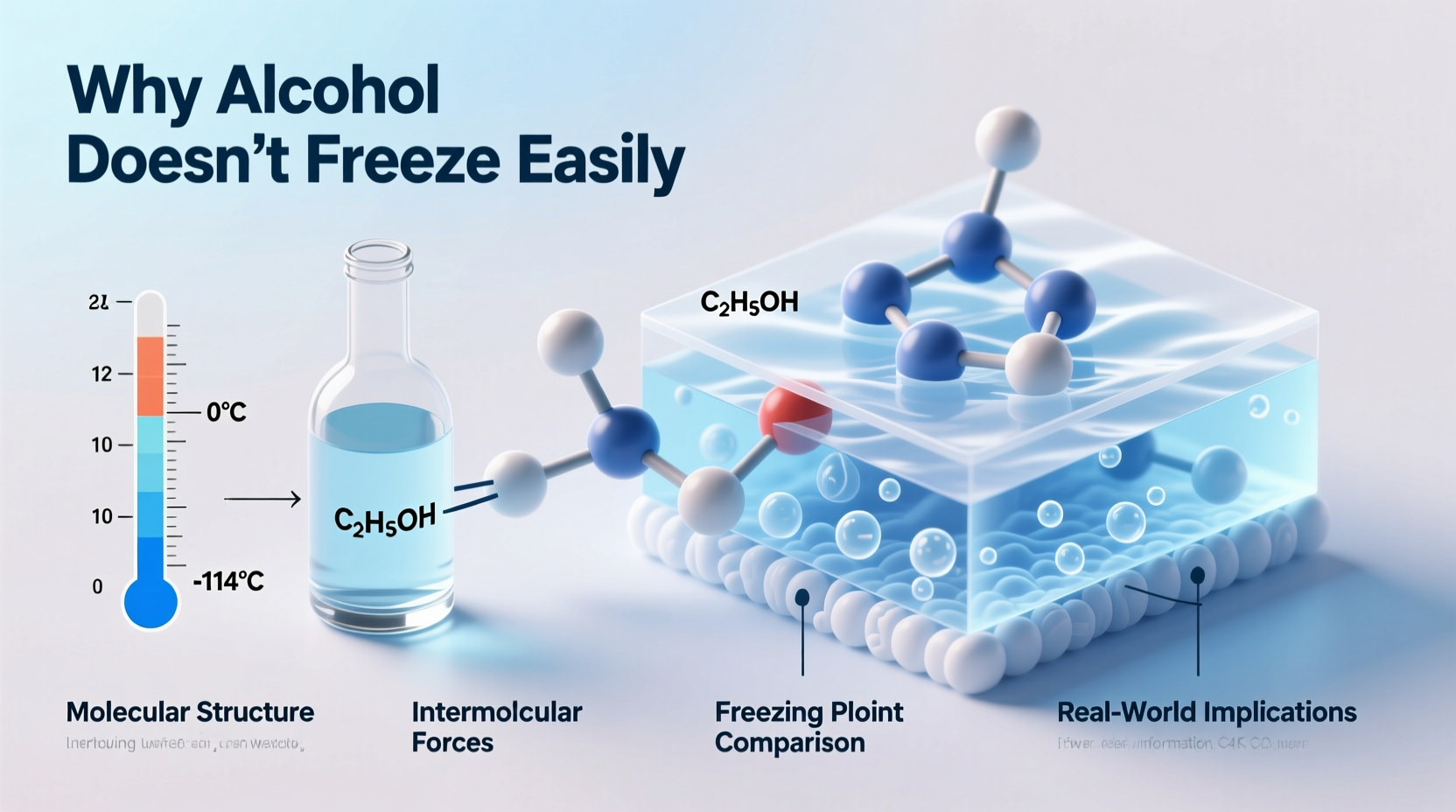

Ethanol, the type of alcohol found in beverages, has a much lower freezing point than water—approximately -114°C (-173°F). When ethanol is mixed with water, it disrupts the hydrogen bonding network that allows water molecules to lock into a solid structure. This interference lowers the mixture’s overall freezing point—a process known scientifically as freezing point depression.

“Mixing alcohol with water doesn’t just dilute the solution—it fundamentally alters its thermodynamic behavior, making it harder for ice crystals to form.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Physical Chemist, University of Colorado

How Alcohol Concentration Affects Freezing

The higher the alcohol content, the lower the freezing point of the mixture. This principle explains why 40% vodka remains liquid in a standard freezer (typically around -18°C or 0°F), while beer or wine may partially freeze.

To illustrate this effect clearly, consider the following table showing approximate freezing points of common alcoholic drinks:

| Beverage | Alcohol by Volume (ABV) | Approximate Freezing Point |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 0% | 0°C (32°F) |

| Beer | 4–6% | -2°C to -3°C (28°F to 27°F) |

| Wine | 12–14% | -5°C to -7°C (23°F to 19°F) |

| Vodka (40%) | 40% | -27°C (-17°F) |

| Rum (50%) | 50% | -36°C (-33°F) |

| Pure Ethanol | 100% | -114°C (-173°F) |

As shown, household freezers are generally not cold enough to freeze spirits like vodka or whiskey. While the water component may begin forming slushy crystals, the ethanol prevents complete solidification.

Real-World Example: The Frozen Margarita Machine

A commercial frozen margarita machine operates on the principles of freezing point depression. These machines maintain a slushy consistency by continuously stirring a mixture of tequila (typically 35–40% ABV), lime juice, and syrup. The constant agitation prevents full crystallization, while the alcohol content ensures the drink remains pourable at temperatures around -5°C to -10°C.

In contrast, attempting to replicate this at home by placing a margarita mix in the freezer often results in either a fully liquid drink (if stirred too late) or a partially frozen block (if left too long). Bartenders and mixologists rely on both alcohol concentration and mechanical control to achieve the ideal texture—demonstrating how theory translates directly into practice.

Step-by-Step: How to Test Alcohol Freeze Resistance at Home

You can observe freezing point depression firsthand with a simple experiment using common household items:

- Gather three small containers and label them: Water, Beer, Vodka.

- Pour equal amounts (about 50 mL) of each liquid into its respective container.

- Place all three in your freezer, ensuring they sit level and undisturbed.

- Check every 30 minutes for up to 4 hours.

- Observe and record the physical state: solid, slushy, or completely liquid.

You’ll likely find that water freezes solid within 2–3 hours, beer becomes slushy with icy patches, and vodka remains almost entirely liquid. This visual demonstration reinforces how alcohol concentration directly impacts phase change behavior.

Applications Beyond the Bar: Industrial and Automotive Uses

The principle of freezing point depression isn’t limited to cocktails. It plays a vital role in various industries:

- Antifreeze in vehicles: Ethylene glycol, chemically similar to ethanol, is added to radiator fluid to prevent engine coolant from freezing in winter.

- De-icing solutions: Airports use alcohol-based fluids (like propylene glycol) to remove ice from aircraft surfaces before takeoff.

- Pharmaceutical preservation: Alcohol is used in some medical solutions to ensure stability at low temperatures during transport.

- Food manufacturing: Ice cream makers sometimes add small amounts of alcohol to keep desserts soft at freezer temperatures.

In each case, the goal is to inhibit ice formation through molecular disruption—just as ethanol does in your favorite spirit.

Common Misconceptions About Alcohol and Freezing

Several myths persist about alcohol and cold temperatures:

- Myth: “Alcohol doesn’t freeze at all.”

Truth: It does—but at extremely low temperatures. Pure ethanol freezes at -114°C. - Myth: “Putting liquor in the freezer will make it stronger.”

Truth: Freezing doesn’t increase alcohol content; it may even cause minor separation over time. - Myth: “All alcoholic drinks can be stored in the freezer safely.”

Truth: Low-ABV drinks like beer can explode if sealed bottles freeze and expand.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you freeze vodka?

No—not in a standard home freezer. Vodka (40% ABV) freezes at approximately -27°C (-17°F), far below the typical freezer temperature of -18°C (0°F). It may become viscous or develop slight ice crystals from the water content, but it won’t solidify.

Why does my bottle of wine have ice chunks in the freezer?

Wine contains only about 12% alcohol, so its freezing point is around -5°C to -7°C. When placed in a freezer, the water begins to crystallize first, leaving behind a more concentrated alcoholic solution. The result is a slushy mix with visible ice fragments.

Does freezing alcohol damage its quality?

For high-proof spirits like whiskey or rum, freezing doesn’t significantly alter flavor or shelf life. However, carbonated alcoholic drinks (e.g., sparkling wine or canned cocktails) may lose fizz or burst due to pressure buildup. Cream-based liqueurs (like Bailey’s) can separate when frozen and thawed, affecting texture and appearance.

Action Checklist: Smart Storage Tips for Alcoholic Beverages

- ✅ Store spirits (above 30% ABV) in the freezer for chilled, ready-to-serve enjoyment.

- ✅ Avoid freezing beer, wine, or cider in glass bottles—they may crack due to expansion.

- ✅ Keep cream liqueurs refrigerated but never frozen.

- ✅ Use plastic or flexible containers if experimenting with freezing lower-alcohol mixes.

- ✅ Label homemade infusions or syrups with alcohol content to predict freeze behavior.

Final Thoughts: Embrace the Science Behind the Chill

The reason alcohol doesn’t freeze easily isn’t magic—it’s chemistry. From your go-to shot of whiskey to airport de-icing procedures, the interaction between alcohol and temperature shapes real-world outcomes. By understanding freezing point depression, you gain more than trivia; you unlock smarter decisions in storage, mixing, and even safety.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?