The human body is a complex structure, and describing its parts accurately requires a universal reference point. In anatomy and medicine, that reference is the anatomical position—a standardized posture used to describe the location and relationship of body structures. Without this consistent framework, communication among healthcare professionals would be prone to confusion, misinterpretation, and potentially dangerous errors. The anatomical position serves as the foundation for all directional terms, medical imaging interpretation, surgical planning, and anatomical education.

What Is the Anatomical Position? A Clear Definition

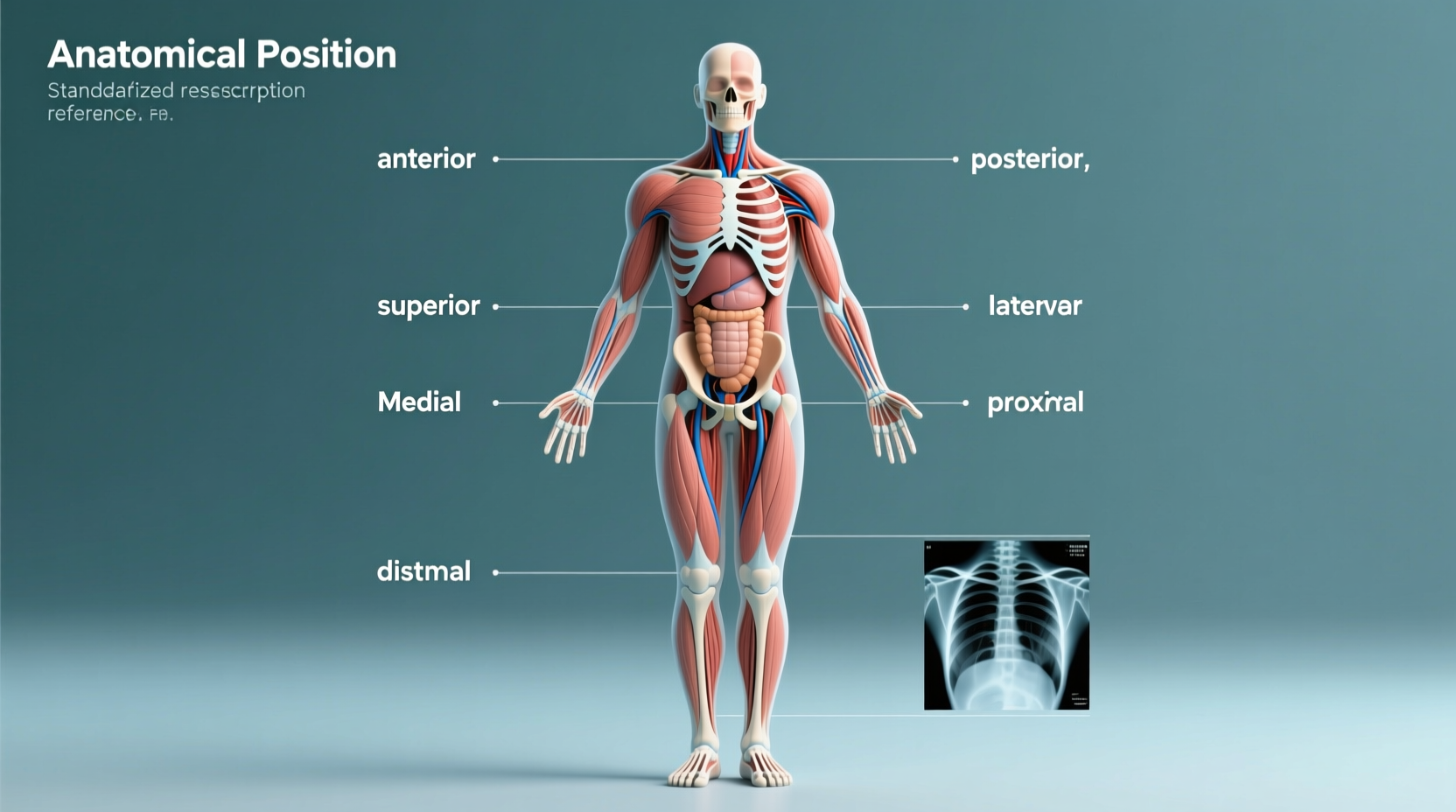

The anatomical position is defined as a body standing upright, facing forward, with feet parallel and flat on the floor, arms at the sides, and palms facing forward. This standardized orientation allows for consistent use of directional terminology such as superior (above), inferior (below), anterior (front), posterior (back), medial (toward the midline), and lateral (away from the midline).

This position may seem intuitive, but it's crucial because many body parts—especially the forearms and hands—undergo rotation during normal movement. By fixing the palms forward, the anatomical position eliminates ambiguity when discussing structures like the radius and ulna or nerves running through the arm.

“Without a standard frame of reference, anatomical descriptions would be chaotic. The anatomical position brings order to the complexity of the human form.” — Dr. Laura Simmons, Professor of Human Anatomy, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Clinical Uses of the Anatomical Position

In clinical settings, precise language saves lives. Whether a radiologist interprets a CT scan or a surgeon plans an incision, everyone must refer to the same spatial understanding of the body. Here are key applications:

- Radiology: Radiologists label images based on the anatomical position. Left and right are reversed from the viewer’s perspective unless corrected—knowing the standard avoids misdiagnosis.

- Surgery: Surgeons rely on directional terms derived from the anatomical position to navigate tissues safely. For example, “the appendix is located in the right lower quadrant” only makes sense within this framework.

- Physical Therapy: Movement assessments use planes of motion—sagittal, frontal, transverse—defined relative to the anatomical position.

- Anatomical Education: Students learn muscle attachments, nerve pathways, and organ locations using consistent terminology rooted in this stance.

Directional Terminology Based on Anatomical Position

All directional terms assume the body is in anatomical position. Misunderstanding these can lead to serious clinical errors. Below is a summary table of essential terms and their meanings:

| Term | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Superior | Toward the head | The heart is superior to the stomach |

| Inferior | Away from the head | The pelvis is inferior to the chest |

| Anterior | Front of the body | The sternum is anterior to the spine |

| Posterior | Back of the body | The scapula is posterior to the ribs |

| Medial | Toward the midline | The nose is medial to the eyes |

| Lateral | Away from the midline | The ears are lateral to the nose |

| Proximal | Closer to the limb’s origin | The elbow is proximal to the wrist |

| Distal | Furthest from the limb’s origin | The fingers are distal to the forearm |

These terms remain constant regardless of the body’s actual position. For instance, even if a person is lying down or bending over, the nose is still anterior and the knee is still superior to the foot in anatomical description.

Step-by-Step: How to Apply Anatomical Position in Practice

Understanding the concept is one thing; applying it correctly in real-world scenarios is another. Follow this step-by-step guide to ensure accurate usage:

- Visualize the Standard Pose: Always begin by mentally placing the body in anatomical position—upright, palms forward—even when dealing with patients in bed or imaging scans.

- Identify the Reference Planes: Determine which plane is being referenced—sagittal (divides left/right), frontal (anterior/posterior), or transverse (superior/inferior).

- Use Correct Terminology: Describe locations using standardized terms instead of colloquial language like “on top of” or “to the side.”

- Check Imaging Labels: Confirm that radiological images are properly oriented—many display patient left on the viewer’s right.

- Communicate Clearly in Teams: During rounds or procedures, use unambiguous terms so all team members interpret directions identically.

Real-World Example: A Case of Miscommunication

A 45-year-old male was scheduled for a biopsy of a suspected lesion. The referring physician noted “a mass on the left side of the neck,” but failed to specify whether this referred to the patient’s left or the observer’s left. The radiologist interpreted it as the patient’s left, while the surgeon initially prepared for the right side from his viewpoint. Fortunately, a pre-op time-out caught the discrepancy. The error was resolved, but it highlighted how easily confusion arises without adherence to anatomical standards.

Had the report used the phrase “a mass on the left side of the neck (patient’s left, anatomical position)” or included directional terms like “lateral to the trachea and superior to the clavicle,” the ambiguity would have been eliminated entirely.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even trained professionals occasionally slip into imprecise language. Here are frequent pitfalls and how to correct them:

- Mistake: Saying “the wound is on top of the leg.”

Correction: Use “anterior thigh” or “superior aspect of the femur” depending on context. - Mistake: Describing MRI slices without referencing transverse, sagittal, or coronal planes.

Correction: Specify “axial T1-weighted image at L3 level” for clarity. - Mistake: Using “up” and “down” in teaching environments.

Correction: Replace with “superior” and “inferior” consistently.

Checklist: Ensuring Accuracy in Anatomical Communication

Use this checklist whenever documenting, presenting, or discussing anatomical information:

- ✅ Confirm the body is mentally placed in anatomical position

- ✅ Use directional terms (e.g., medial, distal) instead of vague descriptors

- ✅ Double-check left/right labels in imaging reports

- ✅ Specify anatomical planes when describing sections or movements

- ✅ Review team communications for ambiguous language before procedures

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do we use palms-forward in anatomical position?

The palms-forward orientation reflects the natural alignment of the upper limbs when standing neutrally with thumbs pointing away from the body. It standardizes the relationship between the radius and ulna, ensuring consistent description of nerves and vessels in the arm and forearm.

Does the anatomical position apply to animals too?

In veterinary anatomy, a similar concept exists but is adapted for quadrupeds. Animals are described as standing on all four limbs, with the head and tail aligned horizontally. Terms like cranial (instead of superior) and caudal (instead of inferior) are used to reflect differences in posture.

What happens if we don’t use anatomical position?

Without it, there would be no consistent way to describe structures. A term like “above the knee” could mean anterior, posterior, or superior depending on context. This lack of precision increases the risk of diagnostic errors, surgical mistakes, and educational confusion.

Conclusion: The Unseen Foundation of Medical Precision

The anatomical position is more than a classroom diagram—it’s a critical tool that ensures accuracy, safety, and clarity across every field of medicine. From the first day of medical school to high-stakes surgeries, this simple stance underpins effective communication. Its value lies not in complexity, but in consistency. By adhering to this universal standard, healthcare providers protect patients, enhance collaboration, and uphold the integrity of anatomical science.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?