Cheesecake is a beloved dessert found in bakeries, restaurants, and home kitchens around the world. Despite its name, many people question whether it truly qualifies as a \"cake.\" The answer lies not just in ingredients but in history, linguistics, and culinary tradition. Understanding why it’s called cheesecake involves tracing its ancient roots, examining its evolution across civilizations, and clarifying its place within modern food classification systems.

The Etymology of “Cheesecake”

The term “cheesecake” is a compound noun: “cheese” + “cake.” At face value, this suggests a cake made primarily from cheese. While that may sound unusual to some, the name reflects both ingredient composition and structural form. Unlike traditional cakes leavened with flour and eggs, cheesecakes rely on soft, fresh cheeses—most commonly cream cheese today—as their base.

The word itself dates back to at least the 15th century in English texts, though the concept is far older. Early versions were recorded under variations like “cheese cake” or “tartes de fromage,” emphasizing the dairy element baked into a pastry-like shell. Over time, “cheesecake” became standardized as one word, cementing its identity as a distinct dessert category.

Ancient Origins: From Greece to Rome

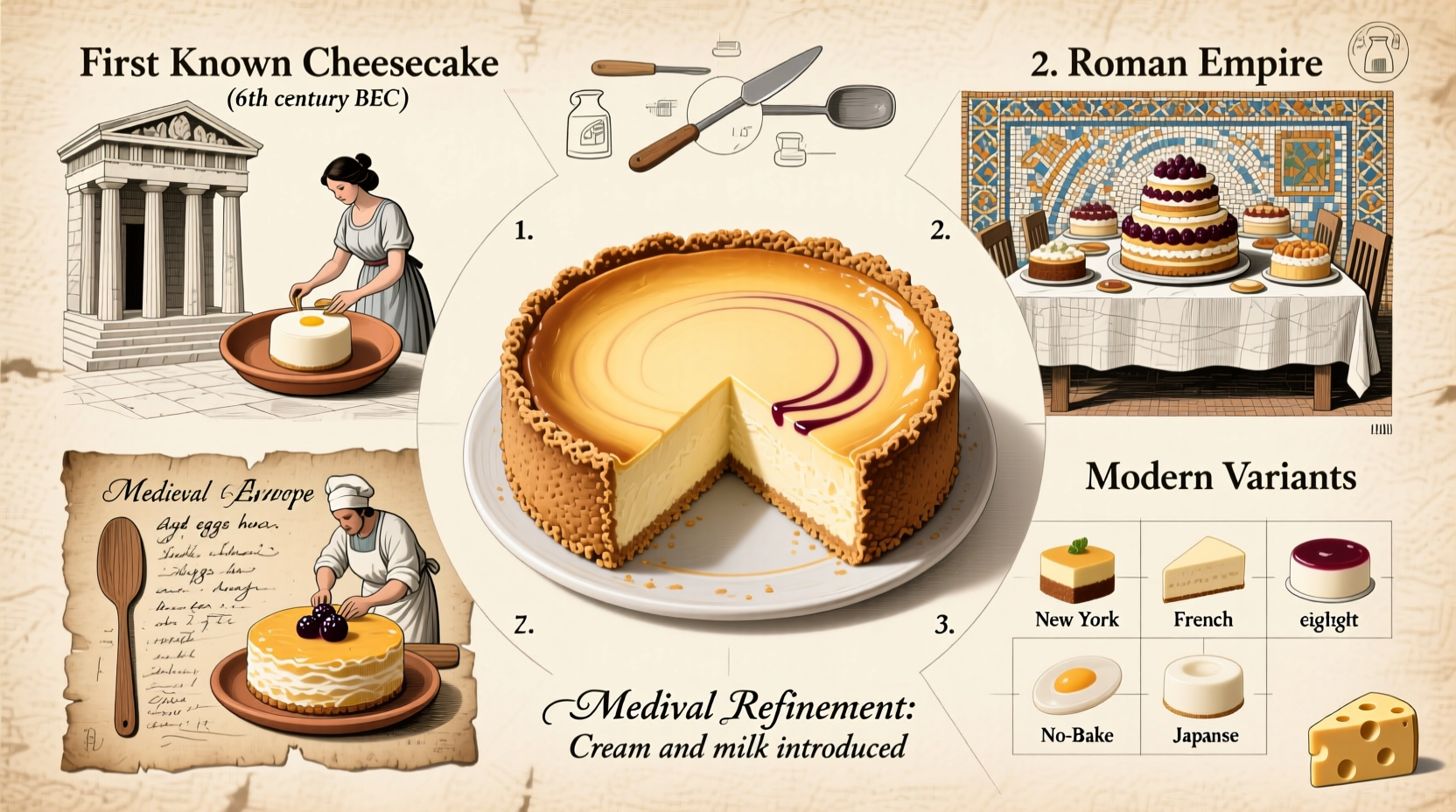

The earliest known version of cheesecake originated in ancient Greece around the 5th century BCE. It was served to athletes during the first Olympic Games in 776 BCE as a source of strength and energy. This early iteration, known as *plakous*, consisted of fresh cheese layered with honey and wheat, then flattened and baked. The result was dense, slightly sweet, and nutritious—a far cry from today’s creamy New York-style slices, yet unmistakably part of the same lineage.

When the Romans conquered Greece, they adopted and adapted the recipe. Their version, called *libum*, often included crushed grains and was used as an offering in religious ceremonies. Apicius, a Roman gourmet, documented several cheesecake-like recipes in his cookbook *De Re Coquinaria*, using simple ingredients like flour, cheese, and egg—all baked slowly.

“Cheesecake began not as indulgence, but as sustenance and ritual food.” — Dr. Elena Moretti, Food Historian, University of Gastronomic Sciences

Classification: Is Cheesecake Actually a Cake?

This question arises frequently in culinary debates. By modern standards, cakes are typically light, fluffy, and sweetened baked goods made with flour, sugar, eggs, butter, and leavening agents. Cheesecakes diverge significantly:

- They lack significant flour content.

- They are denser and richer due to high dairy concentration.

- Many are no-bake or only lightly baked (especially modern varieties).

Despite these differences, cheesecake retains key characteristics of a cake: it is portioned, often layered, and served as a dessert centerpiece. Culinary experts classify it as a “custard pie” or “baked custard tart” rather than a true cake. However, because of its cultural association and presentation—served in slices, often decorated, and celebrated at events—it remains colloquially labeled a cake.

| Feature | Traditional Cake | Classic Cheesecake |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Base | Flour & Sugar | Cream Cheese & Eggs |

| Leavening Agent | Baking Powder/Soda | Eggs (for structure) |

| Texture | Light & Airy | Dense & Creamy |

| Crust | Rarely present | Common (graham cracker, pastry) |

| Baking Method | Oven-baked | Oven-baked or No-Bake |

In formal classifications such as those by the USDA or professional pastry guilds, cheesecake falls under “dairy-based desserts” or “refrigerated pies,” depending on preparation. Yet public perception, shaped by decades of branding and menu placement, keeps it firmly in the “cake” category.

Global Variations and Cultural Identity

As cheesecake traveled through Europe and into Asia and the Americas, it evolved dramatically. Each region reinterpreted the basic formula to suit local tastes and available ingredients, further complicating its classification.

- Italy: Uses ricotta instead of cream cheese, resulting in a lighter texture. Often flavored with citrus or chocolate.

- Germany (Käsekuchen): Typically lower in sugar, sometimes includes quark cheese, and may be topped with fruit compote.

- Japan: Famous for its soufflé-style cheesecake—jiggly, airy, and barely set. Baked in water baths and cooled before serving.

- United States: Dominated by the rich, dense New York-style cheesecake, popularized in the early 20th century by Jewish-American bakeries.

These variations show that while the core idea—sweetened cheese in a structured dessert—remains consistent, the execution varies widely. This diversity reinforces the idea that “cheesecake” is less a rigid recipe and more a conceptual framework for a class of desserts.

Mini Case Study: The Rise of Junior’s Restaurant, Brooklyn

Founded in 1950, Junior’s in downtown Brooklyn became synonymous with New York-style cheesecake. Its signature slice—thick, velvety, and balanced between sweetness and tang—helped standardize what Americans now expect from cheesecake. Despite lacking flour-heavy layers or frosting, Junior’s marketed its product explicitly as “cheesecake,” reinforcing the term in mainstream culture.

Their success illustrates how branding and consistency can shape culinary categorization. Even without fitting the technical definition of cake, Junior’s cheesecake occupies the same emotional and ceremonial space—celebrations, holidays, romantic dinners—proving that function often matters more than form.

Why the Name Stuck: Language, Marketing, and Tradition

Linguistically, naming a dish after its dominant ingredient is common. Think meatloaf, chicken pot pie, or peanut butter cookies. “Cheesecake” follows this pattern—it highlights the star component. Calling it a “cheese tart” might be more accurate in some contexts, but lacks the familiarity and warmth associated with “cake.”

Marketing has also played a crucial role. In the early 20th century, as cream cheese became widely available (thanks to brands like Philadelphia), manufacturers promoted recipes featuring their product. Advertisements referred to them as “cheesecakes,” linking the brand to the dessert in consumers’ minds. This commercial push helped solidify the name in American vernacular.

“The term ‘cheesecake’ won because it was simple, descriptive, and marketable.” — Prof. Daniel Liu, Department of Food Studies, NYU

Step-by-Step Timeline of Cheesecake Evolution

- 5th Century BCE: Greeks create *plakous*, an early form of cheesecake using fresh cheese, honey, and wheat.

- 1st Century CE: Romans adopt and modify the recipe, adding eggs and baking it in pastry shells.

- 1400s–1600s: “Cheese cake” appears in English cookbooks, often as a spiced, baked tart.

- 1872: William Lawrence invents modern cream cheese in New York, later trademarked as Philadelphia.

- Early 1900s: Jewish immigrants in New York adapt European cheesecake recipes using cream cheese.

- Mid-20th Century: Bakeries like Lindy’s and Junior’s popularize thick, rich New York-style cheesecake.

- 1970s–Present: Global variations emerge—Japanese soufflé, Italian ricotta, no-bake instant versions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is cheesecake technically a pie?

From a culinary standpoint, yes—many food scientists classify baked cheesecake as a custard pie because it has a filling set in a crust and relies on eggs for structure. However, culturally and linguistically, it’s treated as a cake due to its celebratory role and naming convention.

Why is it called cheesecake if there’s no cake in it?

The name refers to the form and function, not literal cake ingredients. Like “potpie” isn’t made of pie dough alone, “cheesecake” describes a structured dessert centered around cheese. The absence of flour doesn’t negate its status as a cake in popular usage.

Can vegans enjoy cheesecake?

Yes. Modern plant-based alternatives use cashews, tofu, or coconut milk to mimic the creamy texture. These are often labeled “vegan cheesecake” and follow the same structural format—crust, filling, chill-set—while remaining dairy-free.

Conclusion: Embracing the Paradox

Cheesecake defies easy categorization, existing at the intersection of pie, custard, and cake. Its name, rooted in simplicity and ingredient focus, has endured centuries of culinary change. Whether enjoyed in ancient Olympia or modern Tokyo, cheesecake transcends labels through its universal appeal: rich, comforting, and deeply satisfying.

Understanding its origins and classification doesn’t diminish its magic—it enhances appreciation for how food evolves through culture, language, and innovation. The next time you take a bite of creamy cheesecake, remember: it’s not just dessert. It’s edible history.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?