Baking bread at home should be a rewarding experience—watching a soft ball of dough transform into a golden, aromatic loaf is nothing short of alchemy. But when your dough refuses to rise, the process can quickly turn frustrating. You’ve measured the ingredients, kneaded with care, and waited patiently, only to find a dense lump where a light, airy loaf should be. The most common culprits? Yeast performance and temperature inconsistencies. Understanding how these factors interact is essential for diagnosing and fixing flat dough.

Yeast is a living organism, and like any living thing, it has specific needs to thrive. Temperature plays a crucial role in activating yeast and sustaining fermentation. Too cold, and the yeast becomes dormant; too hot, and it dies. Even subtle missteps in handling or environment can derail an entire bake. This guide dives deep into the science behind dough rising, identifies the most frequent causes of failure, and provides actionable solutions so you can consistently produce beautifully risen loaves.

Understanding How Yeast Works in Bread Dough

Yeast, specifically *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, is the engine behind bread’s rise. When mixed with water, flour, and sugar, yeast consumes carbohydrates and produces carbon dioxide gas and alcohol through fermentation. The gas gets trapped in the gluten network formed during kneading, causing the dough to expand. This biological process is delicate and highly sensitive to environmental conditions.

Fresh, active yeast should begin producing bubbles within 5–10 minutes when proofed in warm water (around 105°F to 110°F). If there’s no visible activity, the yeast may be dead or inactive. However, even if the yeast appears active initially, problems later in fermentation can still occur due to temperature fluctuations, ingredient imbalances, or poor dough structure.

Different types of yeast behave differently:

- Active Dry Yeast: Requires rehydration in warm water before use.

- Instant Yeast: Can be mixed directly into dry ingredients; slightly more potent than active dry.

- Fresh Cake Yeast: Perishable and must be stored refrigerated; less common in home kitchens today.

Misidentifying yeast types or using expired product is a frequent cause of failed rises. Always check expiration dates and store yeast properly—ideally in the freezer for long-term use.

Temperature: The Hidden Factor Behind Dough Failure

Temperature governs every stage of bread fermentation. The ideal dough temperature after mixing is between 75°F and 78°F (24°C–26°C). This range supports optimal yeast activity without encouraging off-flavors or killing the culture.

Many home bakers overlook ambient kitchen temperature. A chilly winter kitchen (below 65°F) slows fermentation dramatically. Conversely, placing dough near a heat source—like an oven that cycles on and off—can create uneven rising or kill yeast if temperatures exceed 130°F.

Proofing environments matter just as much as initial mix temperature. A consistent, warm spot encourages steady gas production. Common makeshift proofing areas include:

- The top of the refrigerator (naturally warm from the motor)

- Inside a turned-off oven with a bowl of hot water

- A microwave with a cup of boiling water (creates a mini greenhouse effect)

“Dough is like a baby—it thrives in a stable, warm environment. Fluctuations stress the yeast and disrupt gluten development.” — Dr. Linda Collister, Artisan Baking Scientist

Using a digital thermometer to check dough temperature post-mixing helps maintain consistency. Professional bakers often adjust water temperature based on room conditions to hit the target dough temp precisely.

Common Causes and Solutions for Dough That Won’t Rise

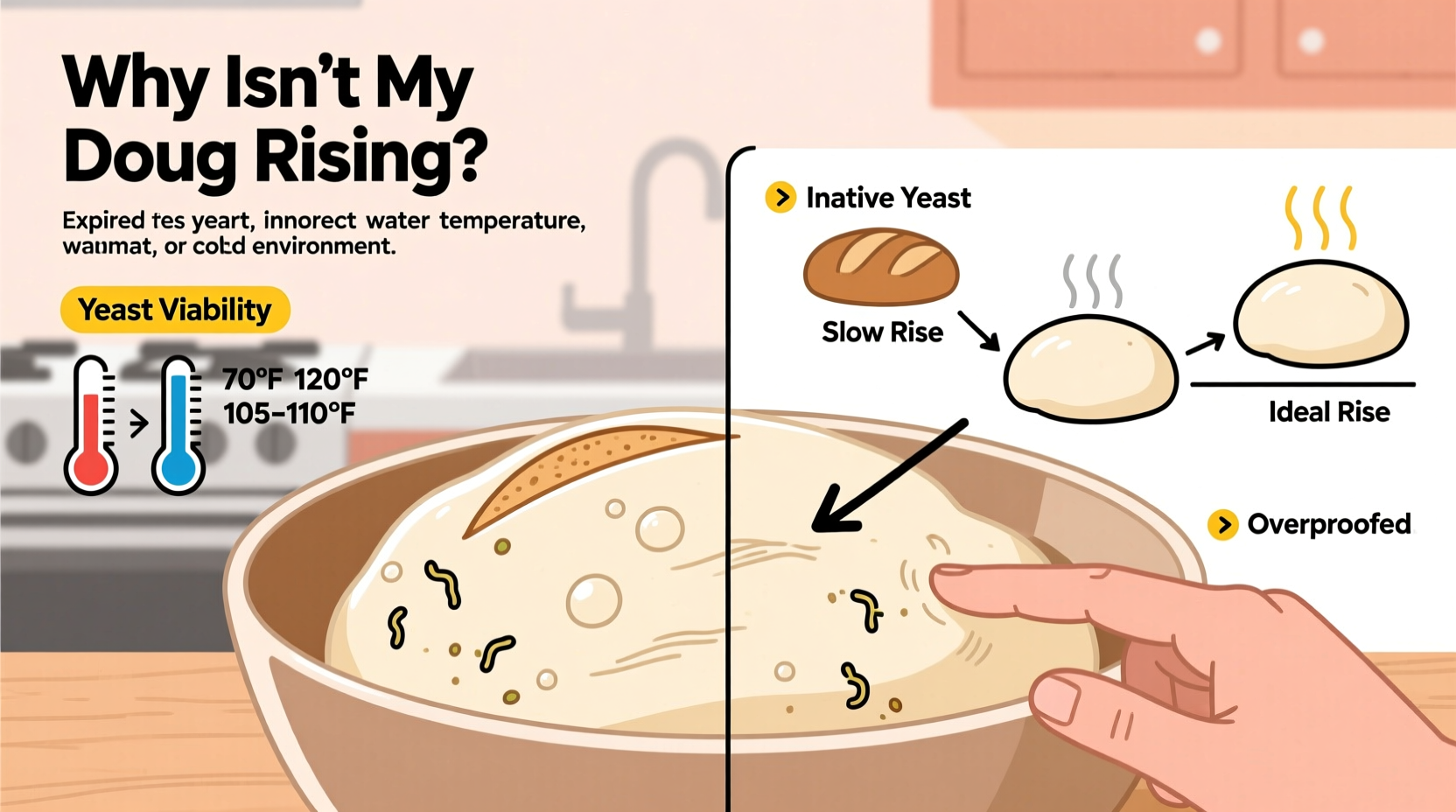

When dough fails to rise, the root cause usually falls into one of several categories. Below is a detailed breakdown of the most frequent issues and how to fix them.

1. Dead or Inactive Yeast

Yeast has a shelf life. Expired yeast won’t ferment, regardless of other conditions. Even unexpired yeast can die if exposed to extreme temperatures during storage or mixing.

2. Water Temperature Too Hot or Too Cold

Water above 130°F kills yeast instantly. Below 95°F, activation is sluggish. The sweet spot is 105°F–110°F for dissolving active dry yeast.

3. Cold Kitchen or Drafty Environment

Drafts from windows, air conditioning, or refrigerators cool dough rapidly. Even brief exposure can stall fermentation.

4. Insufficient Sugar or Food for Yeast

While flour provides most of the carbohydrates yeast feeds on, small amounts of sugar accelerate initial activity. Doughs with whole grains or low-sugar formulations may rise more slowly.

5. Overuse of Salt

Salt strengthens gluten but inhibits yeast. Adding salt directly to undiluted yeast or exceeding recommended amounts (typically 1.8–2% of flour weight) can suppress fermentation.

6. Poor Gluten Development

If dough isn’t kneaded sufficiently—or if weak flour is used—the gluten matrix can’t trap gas effectively. The result is a dough that ferments but doesn’t visibly rise.

7. Over-Rising or Collapse

Dough can rise too much. Over-proofed dough collapses because the gluten structure weakens and can no longer support the expanding gas. This is often mistaken for “not rising” when, in fact, the rise happened and then failed.

| Issue | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dead yeast | No bubbles during proofing; dough completely inert | Always proof yeast in warm water + sugar first |

| Cold environment | Slow or stalled rise, especially in winter | Use oven with hot water pan or heating mat |

| Too much salt | Dense crumb, minimal expansion | Measure accurately; mix salt separately from yeast |

| Over-proofing | Dough deflates when touched or baked flat | Reduce proofing time; use timer and visual cues |

| Poor flour quality | Sticky, weak dough that won’t hold shape | Use bread flour with 11–13% protein |

Step-by-Step Guide to Reviving and Preventing Flat Dough

If your dough isn’t rising, don’t discard it immediately. Follow this timeline to troubleshoot and potentially save your batch.

- Check Yeast Viability (Minutes 0–10): Mix 1/2 teaspoon yeast with 1/4 cup warm water (105°F–110°F) and 1/2 teaspoon sugar. Wait 10 minutes. If no foam forms, the yeast is dead—start over with fresh yeast.

- Assess Dough Temperature (Minute 10): Insert a thermometer into the dough. If below 70°F, place it in a warmer environment.

- Create a Warm Proofing Space (Minute 15): Turn off oven, place a baking tray with boiling water inside, and put dough in a covered bowl on the rack above. Close door.

- Wait and Monitor (Hours 1–2): Check dough every 30 minutes. It should increase by 50–100%. Gently poke it—if the indentation slowly springs back, it’s ready.

- Evaluate After First Rise (Hour 2+): If still flat, consider adding a new batch of proofed yeast (1/2 tsp dissolved), gently folding it in, and reproofing.

- Adjust for Next Time: Record room temperature, water temp, and rise times to refine future attempts.

This methodical approach helps isolate variables and identify what went wrong. Repeating the process with adjustments builds confidence and consistency.

Real Example: From Failed Loaf to Perfect Rise

Sarah, a home baker in Minnesota, struggled for months with dense sourdough-style loaves. Her kitchen averaged 62°F in winter, and she used tap water straight from the faucet—often too cold to activate yeast. She assumed her recipe was flawed and switched flours repeatedly.

After reading about dough temperature control, she began measuring her water (heating it to 110°F) and placing her dough in the oven with a bowl of hot water. Within days, her loaves doubled in size and developed an open crumb. The change wasn’t in ingredients—it was in environment. By stabilizing temperature, she transformed inconsistent results into reliable success.

Her story highlights a common oversight: many assume ingredients are the primary variable, when in fact, external conditions often make the biggest difference.

Essential Checklist for Successful Dough Rising

Use this checklist before every bake to prevent avoidable failures:

- ✅ Check yeast expiration date

- ✅ Proof yeast in warm water (105°F–110°F) with sugar

- ✅ Use a thermometer to verify water and dough temperature

- ✅ Mix salt separately to avoid direct contact with yeast

- ✅ Knead until smooth and elastic (windowpane test passes)

- ✅ Place dough in a lightly oiled, covered bowl

- ✅ Choose a warm, draft-free proofing location

- ✅ Allow 1–2 hours for first rise (or longer in cold climates)

- ✅ Perform the finger poke test to check readiness

- ✅ Preheat oven fully before baking to ensure proper oven spring

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I rescue dough that hasn’t risen?

Yes, in many cases. If the yeast is still alive, warming the dough and giving it more time may help. If yeast is dead, mix in a new batch of proofed yeast, fold gently, and reproof. Avoid adding too much extra flour during reworking.

How long should bread dough take to rise?

Under ideal conditions (75°F–78°F), most doughs double in 1–2 hours. Cooler temperatures extend this—some bakers refrigerate dough overnight for flavor development. Whole grain and sourdough varieties often require longer rise times.

Does altitude affect dough rising?

Yes. At high altitudes (above 3,000 feet), lower atmospheric pressure allows gases to expand faster, which can cause over-rising and collapse. Bakers at elevation often reduce yeast by 25%, shorten proofing times, and increase liquid slightly to compensate for drier air.

Final Thoughts: Mastering the Basics for Reliable Results

Bread baking is equal parts science and patience. While recipes provide a roadmap, success ultimately depends on understanding the behavior of living ingredients and their environment. Yeast is forgiving when treated with care, but unforgiving of neglect. Temperature control isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity.

By treating yeast as a living culture, monitoring your kitchen climate, and following a disciplined process, you’ll eliminate guesswork and build confidence in your baking. Each loaf teaches something new, whether it rises perfectly or ends up as a learning experience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?