At first glance, it seems counterintuitive: on overcast days, when sunlight is diffused and the world appears softer, your shadow often looks sharper and darker than on bright, sunny days. This optical phenomenon defies common expectations. After all, shouldn’t shadows be fainter when the sun is hidden? Yet many people notice that their silhouette cast on pavement or walls under cloud cover has a more defined, almost unnaturally deep blackness compared to the hazy, blurred edges seen in full sunlight. The answer lies not in magic but in the subtle physics of light scattering, angular diffusion, and how our eyes interpret contrast.

This article explores the science behind this curious observation, breaking down the mechanics of shadow formation, the role of clouds in altering light quality, and why perception plays a key part in what we see. Whether you're a photographer, outdoor enthusiast, or simply someone who’s paused mid-step to study their own shadow, understanding these natural light quirks offers insight into one of nature’s quiet visual paradoxes.

The Basics of Shadow Formation

A shadow forms when an opaque object blocks a source of light. In daylight, the primary source is the sun—a distant, intense point of illumination. When your body intercepts direct sunlight, it prevents photons from reaching the surface behind you, creating a region of reduced brightness: your shadow.

Shadows have two main components:

- Umbra: The central, darkest part where all direct light is blocked.

- Penumbra: The outer, partially shaded region where only some of the light is obstructed.

On a clear day, the sun acts as a small, concentrated light source in the sky. Because it has angular size (about 0.5 degrees), light reaches us from slightly different directions across its disk. This creates a soft penumbral edge around shadows, giving them a gradient fade rather than a hard cutoff.

However, introduce clouds into the equation, and the rules change—not because the sun becomes stronger, but because the way light arrives at Earth transforms dramatically.

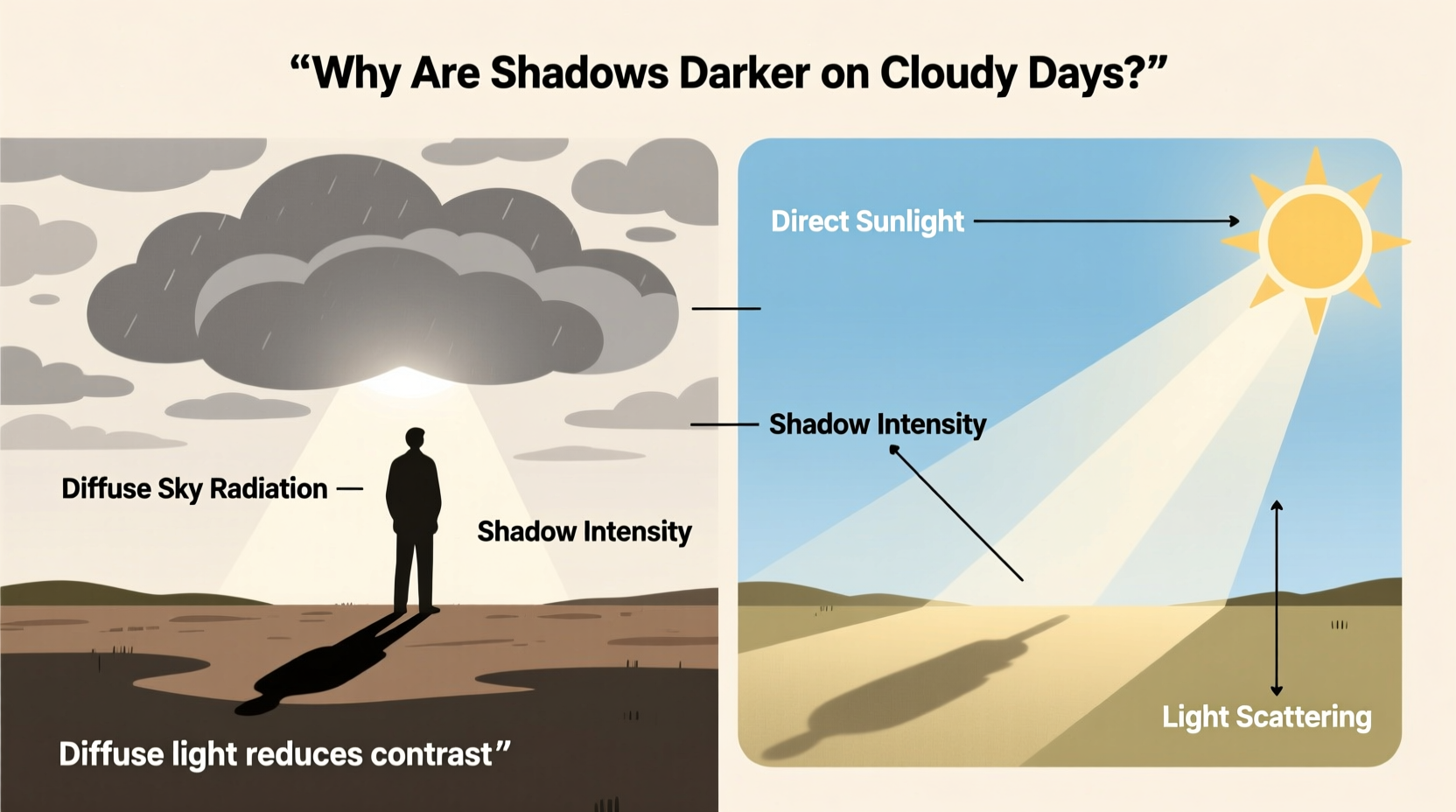

How Clouds Transform Light: Diffusion vs. Directionality

Clouds are not just barriers to sunlight; they are dynamic diffusers. When sunlight encounters a thick layer of water droplets or ice crystals in clouds, it scatters in multiple directions through a process called Mie scattering. Instead of traveling in a straight line from the sun, light bounces off countless particles, spreading out evenly across the sky.

This turns the entire sky into a broad, secondary light source—much like a giant softbox used in studio photography. As a result, illumination becomes omnidirectional, reducing harsh contrasts and eliminating strong highlights. That’s why faces appear more evenly lit and glare diminishes on overcast days.

But here’s the twist: while ambient light increases due to scattering, the intensity of *direct* sunlight drops significantly. On heavily overcast days, up to 80–90% of direct solar radiation may be blocked. What remains is diffuse skylight—gentle, widespread, and lacking strong directional cues.

Why Less Direct Light Means Darker Shadows

Paradoxically, the absence of competing ambient light makes shadows appear deeper. Here’s why:

Under full sun, even the area within your shadow receives some indirect illumination—light reflected off nearby surfaces, scattered by air molecules (Rayleigh scattering), or entering from the blue sky surrounding the sun. This “fill light” brightens the shadow zone, reducing its contrast with the surroundings.

Under thick cloud cover, although overall scene brightness can remain high, the directional component vanishes. There is no strong backlight or sidelight to wrap around your body and illuminate the shadowed area. The diffuse glow comes uniformly from above, meaning once your form blocks that dominant overhead source, there's little alternative light to fill in the gap.

In effect, your shadow becomes a void—an area shielded from the only significant source now available: the overcast sky dome. With minimal lateral or reflected light to dilute it, the shadow appears subjectively darker and more sharply defined, even if technically less contrasty in absolute terms.

Perception and Contrast: The Role of Human Vision

The human eye doesn’t measure light objectively—it adapts dynamically based on context. Our perception of darkness depends heavily on surrounding brightness, a principle known as simultaneous contrast.

On a bright sunny day, large areas of high luminance (sunlit ground, reflective surfaces) surround your shadow. Your pupils constrict, and your visual system adjusts to the high overall brightness. Within this context, your shadow appears relatively dark—but because there’s still considerable ambient light within it, the brain registers it as “soft” or “faded.”

On a cloudy day, the entire scene operates at a lower dynamic range. Surfaces reflect less peak light, so your eyes adapt to a dimmer baseline. When your shadow falls on this already subdued background, the relative drop in brightness feels more pronounced. Even if the absolute difference between lit and unlit areas is smaller, the perceptual contrast increases.

“On overcast days, shadows gain psychological weight. They feel heavier because the visual environment lacks competing hotspots.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Cognitive Vision Researcher, University of Oslo

This perceptual amplification explains why many artists and photographers describe cloudy-day shadows as “crisper” or “more present,” even though instruments might show lower contrast ratios. It’s not about physics alone—it’s about how the brain interprets spatial boundaries in low-glare environments.

Real-World Example: A Photographer’s Field Observation

In 2021, landscape photographer Marcus Bell was shooting urban silhouettes in Edinburgh during shifting weather. His goal was to capture pedestrian shadows elongated by low-angle winter light. On a clear morning, he noticed that while shadows were long, they lacked definition—their edges blurred by atmospheric haze and ground reflections.

By afternoon, clouds rolled in. Sunlight disappeared, yet Bell decided to continue shooting. To his surprise, images taken under full overcast showed pedestrians’ shadows with striking clarity. Despite lower light levels, the outlines were more distinct, with richer blacks and cleaner separation from the sidewalk.

Upon reviewing histograms and exposure data, he found that shadow regions recorded lower luminance values under clouds—even though overall scene exposure was similar. The reason? Minimal fill light. Without direct sun bouncing off adjacent buildings or pavement, the shadow zones received almost no secondary illumination. The camera captured what his eyes perceived: a deeper, more complete absence of light.

Bell later wrote in his field journal: “The cloud didn’t make the shadow darker in watts per square meter—it made it *more total*. And totality reads as depth.”

Comparing Shadow Characteristics Across Conditions

| Condition | Light Source Type | Shadow Edge Quality | Perceived Darkness | Fill Light Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear Sky, Midday | Direct Sun (small source) | Soft edges, wide penumbra | Moderate (high ambient) | High (reflections, sky scatter) |

| Thin Cloud Cover | Partially diffused | Mixed sharpness | Variable | Moderate |

| Thick Overcast | Dome-shaped diffuse source | Sharper edges, narrow penumbra | High (perceptually darker) | Very Low |

| Sunset, Clear | Low-angle direct sun | Long, soft shadows | Deep but warm-toned | Low to moderate |

| Foggy Day | Extremely diffused | Almost no visible shadow | Nearly invisible | Uniform in all directions |

Note that fog behaves differently than clouds. While both scatter light, fog scatters it so intensely and close to the observer that directional information is lost entirely. Hence, shadows vanish altogether in dense fog, illustrating the spectrum of diffusion effects.

Practical Tips for Observing and Using This Effect

- Walk barefoot on asphalt: Feel the temperature difference between sunlit and shadowed areas. On cloudy days, the thermal contrast is minimal, reinforcing that the darkness is visual, not thermal.

- Use a white card test: Hold a white piece of paper inside and outside your shadow. On sunny days, the difference is stark; on overcast days, the paper may look nearly identical in both zones—yet your shadow still appears dark.

- Compare edge sharpness: Trace your shadow outline with chalk on both clear and cloudy days. You’ll find edges are more consistent and easier to define under clouds.

Checklist: How to Test Shadow Behavior Yourself

- Choose a flat, uniformly colored surface (e.g., concrete sidewalk).

- Visit the same spot on a clear day and a fully overcast day at similar times.

- Stand in the same position and observe your shadow’s edge definition.

- Take photos using manual exposure settings to avoid auto-brightness interference.

- Compare the images side by side, noting contrast and depth.

- Repeat near reflective surfaces (walls, vehicles) to see how fill light changes results.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can shadows exist without direct sunlight?

Yes. Any dominant light source creates shadows. On cloudy days, the overcast sky acts as a single, large-area source. If your body blocks that diffuse light, a shadow forms—even without seeing the sun.

Why don’t I see colored shadows on cloudy days?

Colored shadows typically occur when multiple independent light sources (like sun and blue sky) illuminate a scene from different angles. Under clouds, light is unified in color temperature (usually neutral or cool gray), so shadows lack chromatic variation.

Do animals notice this shadow effect?

Limited studies suggest birds and reptiles use shadows for navigation and predator detection. While their visual systems differ, any creature relying on contrast cues would perceive increased shadow salience under overcast conditions, especially in open terrain.

Conclusion: Embracing the Paradox of Natural Light

The next time you step outside beneath a blanket of gray clouds and notice your shadow standing out with unexpected intensity, remember: you’re witnessing a delicate balance between physical optics and human perception. The darkness isn’t a sign of stronger light, but of its absence—carefully sculpted by atmospheric diffusion and interpreted by a brain wired to detect edges and boundaries.

Understanding these subtleties enriches how we interact with the everyday world. Photographers harness this knowledge to create mood. Architects consider it when designing shaded public spaces. And curious minds find wonder in the fact that something as simple as a shadow can shift in character depending on whether the sky is clear or cloaked.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?