Sourdough bread, with its tangy flavor and open crumb structure, is a hallmark of artisan baking. Yet many home bakers face the same frustrating issue: a loaf that’s heavy, compact, and lacking in airiness. A dense sourdough isn’t necessarily a failed loaf—it’s often a sign of one or more small missteps in the process. The good news? Most causes are fixable with adjustments to technique, timing, or ingredients. Drawing from years of experience and insights from seasoned bakers, this guide breaks down the most common reasons for dense sourdough and offers practical solutions to help you achieve light, well-risen loaves consistently.

Understanding the Science Behind Sourdough Rise

Sourdough relies entirely on natural fermentation. Unlike commercial yeast, which acts quickly and predictably, a sourdough starter—composed of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria—works more slowly and requires careful management. For a loaf to rise properly, two key processes must occur: gas production during fermentation and structural development through gluten formation.

The wild yeast consumes carbohydrates in the flour and produces carbon dioxide. This gas gets trapped within the elastic network of gluten, causing the dough to expand. If either gas production is insufficient or the gluten structure collapses, the result is a dense interior. Achieving balance between fermentation strength, dough strength, and oven spring is essential for an airy crumb.

“Dense sourdough is rarely about one single mistake. It’s usually a chain reaction caused by underfermentation, weak gluten, or poor heat transfer in the oven.” — Clara Mendez, Artisan Baker & Fermentation Instructor

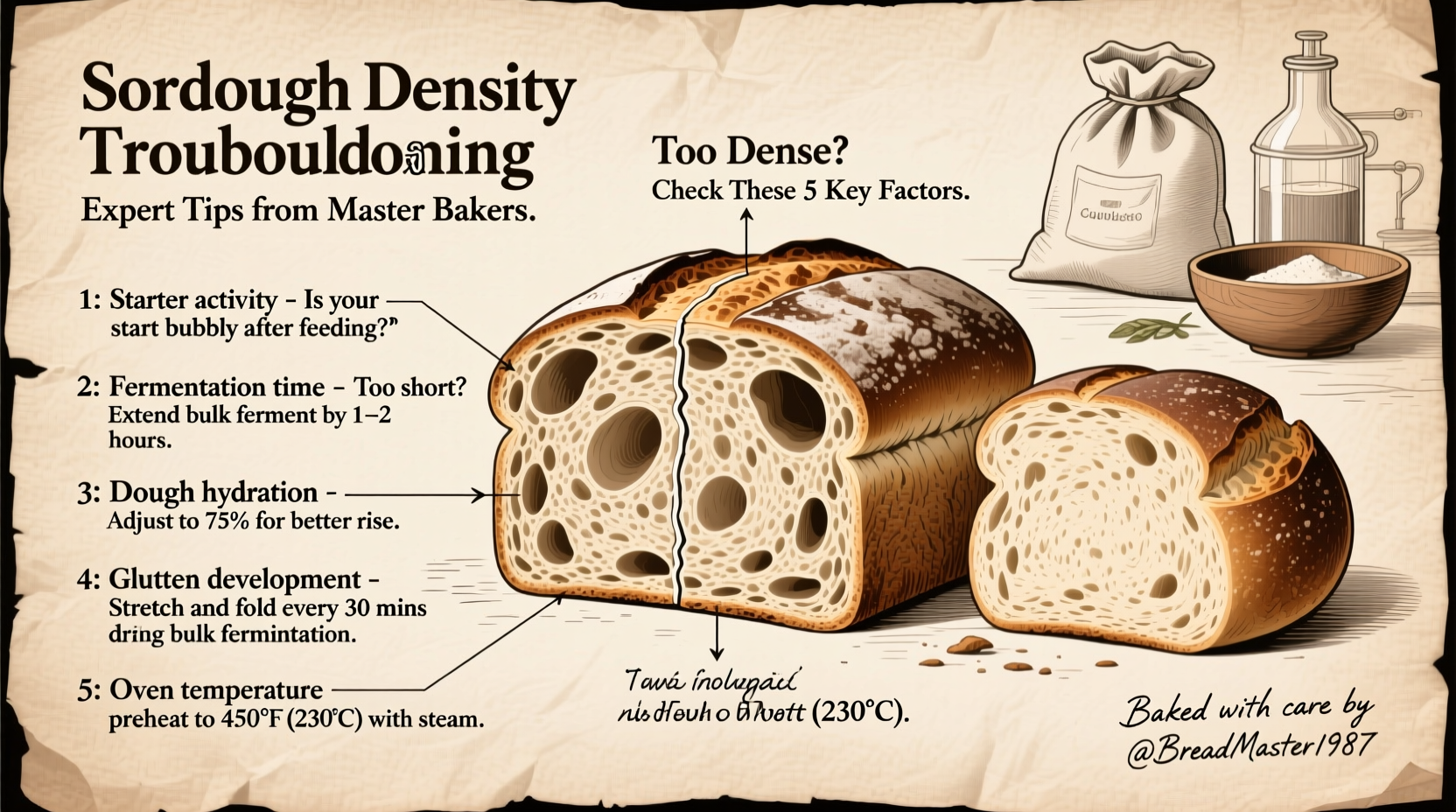

Common Causes of Dense Sourdough (and How to Fix Them)

1. Underactive or Weak Starter

Your starter is the engine of your sourdough. If it's sluggish or not peaking at the right time, your dough won’t generate enough gas to rise properly. A healthy starter should double in size within 4–8 hours after feeding and have a bubbly, frothy appearance.

If your starter smells overly alcoholic or has a layer of gray liquid (hooch), it’s past its peak. While not harmful, using it at this stage reduces leavening power. Refresh it with fresh flour and water and wait until it becomes active again before baking.

2. Inadequate Bulk Fermentation

Bulk fermentation—the first rise after mixing—is where most of the flavor and structure develop. Ending this phase too early results in underdeveloped gluten and insufficient gas production. Conversely, over-fermenting can weaken the gluten, causing the dough to collapse during shaping or baking.

To assess readiness, look for visible bubbles on the surface, a domed top, and increased volume (about 50–75% rise). The dough should feel light and airy when gently prodded. The \"jiggle test\" helps: if the dough wobbles like jelly when shaken, it’s likely ready.

3. Poor Gluten Development

Gluten gives dough its elasticity and ability to trap gas. Without sufficient development, even a well-fermented dough will deflate. This is especially common with high-hydration doughs or flours low in protein.

Kneading isn’t always necessary in sourdough thanks to autolyse and stretch-and-folds, but these techniques must be done correctly. Perform 3–4 sets of stretch-and-folds during the first hour of bulk fermentation, spaced 15–20 minutes apart. This strengthens the gluten matrix without overworking the dough.

4. Incorrect Hydration or Flour Choice

Using too much water can make dough hard to handle and prone to spreading rather than rising. On the other hand, too little hydration leads to stiff, dense loaves. Beginners should start with hydration levels around 70% (e.g., 700g water per 1000g flour).

Flour matters too. All-purpose flour may lack the protein needed for strong structure. Bread flour (12–13% protein) provides better gluten development. Whole grain flours add flavor but absorb more water and weigh down the crumb. Try blending 10–20% whole wheat into white flour for improved nutrition without sacrificing loft.

5. Improper Shaping or Proofing

Shaping creates surface tension, which helps the loaf hold its shape and rise upward instead of outward. A poorly shaped boule will spread and bake flat. After preshaping and bench rest, tighten the surface during final shaping by rotating the dough against the counter with cupped hands.

Proofing duration depends on temperature and starter strength. Room-temperature proofing typically takes 2–4 hours; refrigerated (retarded) proofing takes 8–16 hours. Overproofed dough feels fragile, doesn’t spring back when poked, and may collapse in the oven. Underproofed dough resists indentation and bakes dense due to restricted expansion.

Troubleshooting Checklist: Is Your Process on Track?

Use this checklist to diagnose issues before your next bake:

- ✅ Is my starter doubling within 6–8 hours of feeding?

- ✅ Did I use the starter at peak activity (not collapsed)?

- ✅ Did I perform stretch-and-folds during bulk fermentation?

- ✅ Does the dough feel smooth, elastic, and slightly airy?

- ✅ Was bulk fermentation long enough (but not too long)?

- ✅ Did I create proper surface tension during shaping?

- ✅ Was the final proof timed correctly (not under/over)?

- ✅ Is my oven hot enough (ideally 450°F/230°C or higher)?

- ✅ Am I using steam during the first 20 minutes of baking?

- ✅ Did I preheat my baking vessel (Dutch oven, etc.) thoroughly?

Step-by-Step Guide to Preventing Dense Sourdough

Follow this optimized process to increase your chances of success:

- Feed your starter 6–8 hours before baking. Use equal parts flour and water by weight. Wait until it peaks—doubled in size and full of bubbles.

- Autolyse the flour and water. Mix 1000g flour and 700g water; let rest for 30–60 minutes. This hydrates the flour and jumpstarts gluten development.

- Add starter and salt. Mix thoroughly, then begin stretch-and-folds: 3–4 sets every 15–20 minutes during the first hour of bulk fermentation.

- Monitor bulk fermentation. Let rise at room temperature (72–78°F / 22–26°C) for 3–5 hours, depending on conditions. Look for volume increase, bubbles, and jiggle.

- Preshape and bench rest. Shape loosely into a round, rest for 20–30 minutes uncovered.

- Final shape. Tighten the surface tension and place seam-side up in a floured banneton or seam-side down for free-form proofing.

- Final proof. At room temp: 2–4 hours. In fridge: 8–16 hours. Test with finger poke—should leave a slow-recovering dent.

- Preheat oven and vessel. Heat Dutch oven at 450°F (230°C) for at least 45 minutes.

- Bake with steam. Score the loaf deeply, transfer to hot pot, cover, and bake 20 minutes. Uncover and bake another 20–25 minutes until deep golden brown.

- Cool completely. Wait at least 2 hours before slicing. Cutting too soon releases trapped steam and compresses the crumb.

Do’s and Don’ts: Key Practices Compared

| Practice | Do | Don't |

|---|---|---|

| Starter Use | Use when doubled and bubbly | Use when collapsed or inactive |

| Fermentation Temp | 72–78°F (22–26°C) | Cold kitchen or near drafts |

| Hydration Level | Start with 65–70% | Jump straight to 80%+ as a beginner |

| Oven Setup | Preheat Dutch oven with lid | Bake on a cold tray |

| Cooling | Cool 2+ hours before slicing | Cut immediately for warm bread |

| Scoring | Deep, confident cuts (¼–½ inch) | Shallow or hesitant slashes |

Real Example: From Brick to Boule

Mark, a home baker in Portland, struggled for months with consistently dense loaves. His starter looked active, but his bread had no oven spring and a gummy crumb. He followed recipes exactly but still failed.

After logging his process, he noticed two issues: he was using his starter 2 hours past its peak, and he wasn’t preheating his Dutch oven. He also skipped stretch-and-folds, assuming the long ferment would compensate.

He adjusted: fed his starter the night before, used it at peak, performed four sets of folds, preheated his pot for 50 minutes, and waited 3 hours before cutting. The next loaf had a crisp crust, open crumb, and rose nearly 2 inches in the oven. “It wasn’t one big change,” he said. “It was fixing three small things that added up.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my sourdough dense even though I used a strong starter?

A strong starter alone isn’t enough. Density can stem from underdeveloped gluten, insufficient bulk fermentation, poor shaping, or inadequate oven heat. Even with great leavening power, the dough needs structure and proper baking conditions to rise fully.

Can I fix a dense sourdough by baking it longer?

No. Baking longer won’t improve crumb structure. Overbaking only dries out the loaf or burns the crust. The texture is determined by fermentation and oven spring, not extended baking time. Focus on process adjustments instead.

Does whole wheat flour always make sourdough denser?

Yes, to some extent. Whole wheat contains bran particles that cut gluten strands and reduce elasticity. It also absorbs more water. To counter this, increase hydration slightly and consider blending with bread flour. Autolyse helps hydrate bran and improves workability.

Conclusion: Turn Dense Loaves Into Light Successes

Dense sourdough is a common hurdle, not a dead end. With attention to starter health, fermentation timing, gluten development, and baking technique, you can transform heavy loaves into airy masterpieces. Remember, sourdough is as much about observation as it is about following steps. Learn to read your dough—its texture, rise, and response to handling—and you’ll gain the intuition that separates consistent bakers from occasional ones.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?