The vast blue expanse of the world’s oceans covers more than 70% of Earth’s surface, holding an immense volume of water that sustains countless ecosystems and regulates global climate. Yet one fundamental characteristic defines this water: its saltiness. Seawater averages about 3.5% dissolved salts by weight—primarily sodium chloride, the same compound found in table salt. But how did the oceans become salty in the first place? The answer lies deep within Earth’s geological history, atmospheric chemistry, and the slow but relentless movement of water across land and sea.

Unlike freshwater lakes and rivers, which contain only trace amounts of dissolved minerals, seawater carries a complex mixture of ions accumulated over hundreds of millions of years. This salinity isn’t static; it results from a dynamic balance between inputs from land and outputs to the seafloor. Understanding this process reveals not only the origins of salt in the ocean but also how Earth’s systems are interconnected across time and space.

The Origins of Ocean Salinity

Ocean salinity began shortly after Earth formed around 4.5 billion years ago. In its early stages, our planet was a molten mass bombarded by asteroids and comets. As it cooled, water vapor trapped in the mantle was released through volcanic outgassing, forming clouds and eventually rain. Over millions of years, this precipitation collected in low-lying basins, creating the first primitive oceans.

At first, these early seas were likely much less salty than today’s oceans. However, as rainwater fell onto exposed rocks on land, it began a slow but powerful process of chemical weathering. Rain is naturally slightly acidic due to dissolved carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, forming weak carbonic acid. This acidity enables water to dissolve minerals such as sodium, calcium, potassium, and magnesium from continental rocks.

These dissolved ions were then carried by rivers into the oceans. Once in the sea, most of these elements do not easily escape back into the atmosphere or return to land. Instead, they accumulate over time. Sodium and chloride—the two components of common salt—are particularly resistant to removal, making them the dominant ions in seawater.

“Salinity is not a flaw of the ocean—it’s a fingerprint of Earth’s long-term geochemical evolution.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Marine Geochemist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Key Sources of Salt in the Ocean

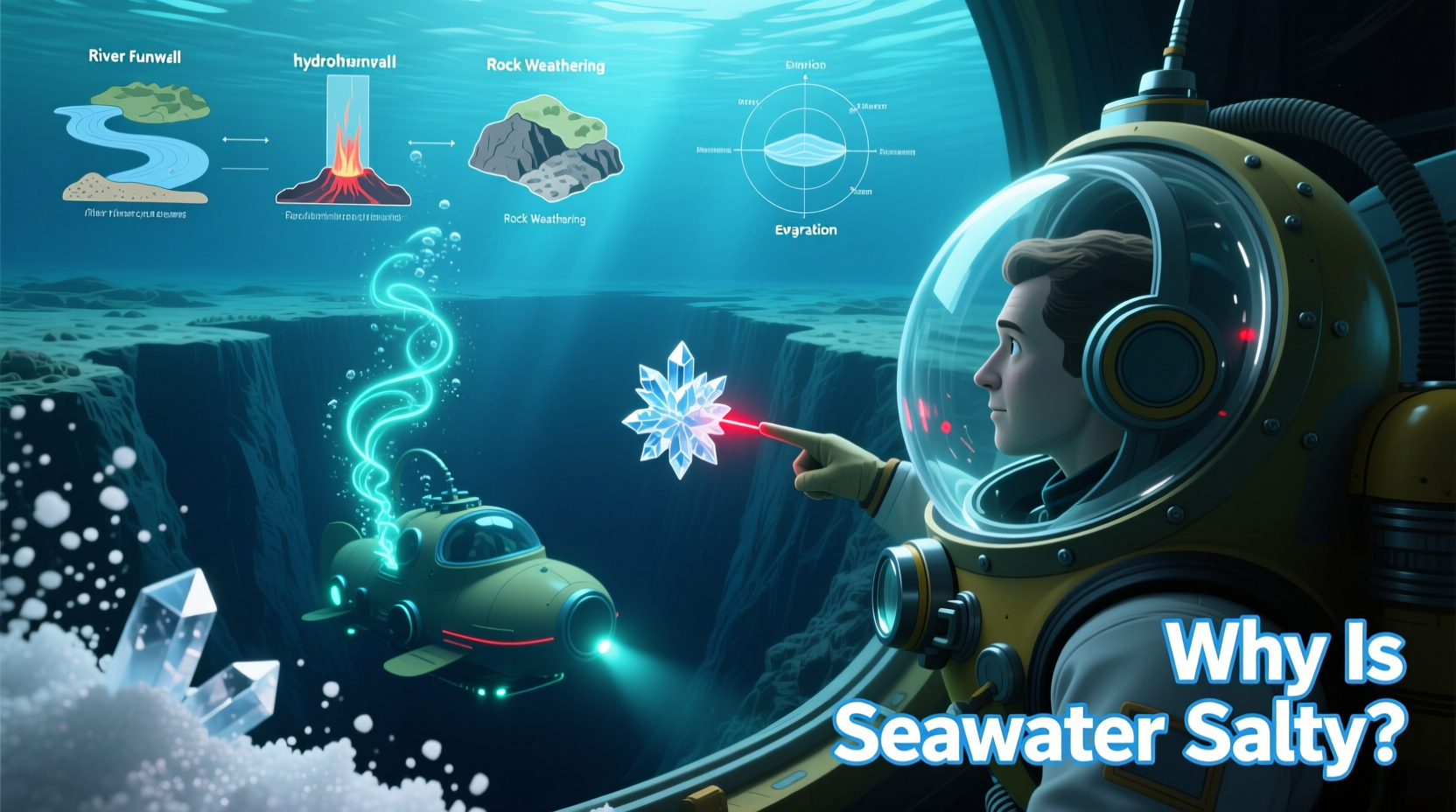

While river input is the most well-known contributor to ocean salinity, it’s not the only source. Several natural mechanisms continuously supply dissolved minerals to the seas:

- River Runoff: Rivers transport billions of tons of dissolved minerals annually from weathered continental rocks into the ocean.

- Hydrothermal Vents: Deep-sea vents along mid-ocean ridges release mineral-rich, superheated water that contributes significant amounts of chloride, sulfur, and other ions.

- Underwater Volcanism: Magma eruptions beneath the ocean floor release gases and minerals directly into seawater.

- Sea Spray and Evaporation: When waves break, tiny droplets containing salt are ejected into the air. While some salt returns via precipitation, this process redistributes sodium and chloride globally.

- Sediment Pore Water: Salts can leach from marine sediments into the overlying water column through slow diffusion.

A Closer Look at Salt Composition

Although we refer to seawater as “salty,” it contains a diverse array of dissolved substances beyond just sodium chloride. The major ions in seawater are remarkably consistent across the globe, regardless of location. This uniformity reflects the ocean’s thorough mixing over time.

| Ion | Chemical Symbol | Average Concentration (g/kg) | Source Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloride | Cl⁻ | 19.3 | Rock weathering, hydrothermal activity |

| Sodium | Na⁺ | 10.8 | Weathering of feldspar and salt deposits |

| Sulfate | SO₄²⁻ | 2.7 | Pyrite oxidation, atmospheric deposition |

| Magnesium | Mg²⁺ | 1.3 | Basalt weathering, hydrothermal vents |

| Calcium | Ca²⁺ | 0.4 | Limestone dissolution, river inflow |

| Potassium | K⁺ | 0.4 | Feldspar breakdown |

This consistency allows scientists to use salinity measurements as a reliable indicator of water mass origin and movement. For example, higher salinity may indicate regions with high evaporation rates, like the subtropical Atlantic, while lower salinity appears near melting glaciers or heavy rainfall zones.

How Salinity Changes Over Time

If salts are constantly added to the ocean, why hasn’t seawater become infinitely salty? The answer lies in natural removal processes that balance the inputs. While rivers add salt continuously, several mechanisms work to remove it:

- Evaporation and Precipitation: In closed basins like the Red Sea, high evaporation increases salinity, while heavy rainfall in tropical zones dilutes it.

- Formation of Evaporite Deposits: When seawater evaporates in shallow basins, salts crystallize and form rock layers (e.g., gypsum, halite). These deposits lock away vast quantities of salt for millions of years.

- Biological Uptake: Marine organisms incorporate calcium and silica into shells and skeletons. When they die, these structures sink and form sedimentary layers like limestone.

- Ion Exchange with Seafloor Basalt: Hydrothermal circulation pulls seawater into hot oceanic crust, where chemical reactions remove magnesium and sulfate and add others like calcium.

- Aeolian Deposition: Wind-blown dust can introduce fresh minerals but also remove salt spray from coastal areas.

Scientists estimate that the average ion in seawater spends about 10 million years dissolved before being removed through one of these pathways. This residence time varies widely—sodium lasts over 200 million years, while aluminum is removed in just a few thousand.

Real-World Example: The Mediterranean Salinity Crisis

One of the most dramatic examples of salinity change occurred around 5.9 million years ago during the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Tectonic shifts closed the Strait of Gibraltar, cutting off the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. With limited inflow and high evaporation rates, the sea began to dry up.

Over tens of thousands of years, massive salt deposits—over a kilometer thick in places—formed across the basin. Eventually, the Atlantic broke through again in a cataclysmic flood known as the Zanclean Deluge, refilling the Mediterranean in what may have been a matter of months. This event illustrates how sensitive ocean salinity can be to changes in geography and climate—and how salt accumulation can shape Earth’s geology.

FAQ

Can the ocean get saltier over time?

On human timescales, no—ocean salinity remains relatively stable due to balanced inputs and outputs. However, climate change is altering regional patterns: some areas are becoming saltier due to increased evaporation, while others are freshening from glacial melt.

Is all seawater equally salty?

No. Surface salinity varies from about 3.1% in polar regions to over 3.8% in subtropical zones like the Arabian Sea. Temperature, rainfall, ice melt, and ocean currents all influence local salinity.

Could desalination significantly reduce ocean salinity?

No. Current desalination plants remove a negligible amount of salt compared to the ocean’s total volume. Even large-scale operations would have no measurable impact on global salinity.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Balance Shaped by Earth Itself

The saltiness of seawater is far more than a curious fact—it’s a testament to Earth’s enduring geological and hydrological cycles. From the slow weathering of mountains to the fiery depths of hydrothermal vents, the ocean accumulates salt through processes that span continents and millennia. Yet nature maintains a delicate equilibrium, removing salts almost as steadily as they arrive.

As climate change alters precipitation, ice melt, and ocean circulation, understanding salinity becomes even more critical. It influences everything from hurricane intensity to marine biodiversity. By studying how and why seawater is salty, we gain deeper insight into the planet’s past—and a clearer view of its future.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?