In American presidential elections, certain states consistently lean toward one party—deep blue or solid red. Others, however, remain unpredictable, shifting support between Democrats and Republicans from one election to the next. These are known as swing states, battleground states, or toss-up states. Their importance cannot be overstated: a single swing state can determine the outcome of an entire election. But what causes a state to become a swing state? And how do demographic, economic, and political forces reshape its electoral identity over time?

This article examines the defining characteristics of swing states, the historical and structural factors behind their volatility, and how changes in population, policy, and partisanship transform once-safe states into competitive arenas.

Defining Swing States: Key Terms and Concepts

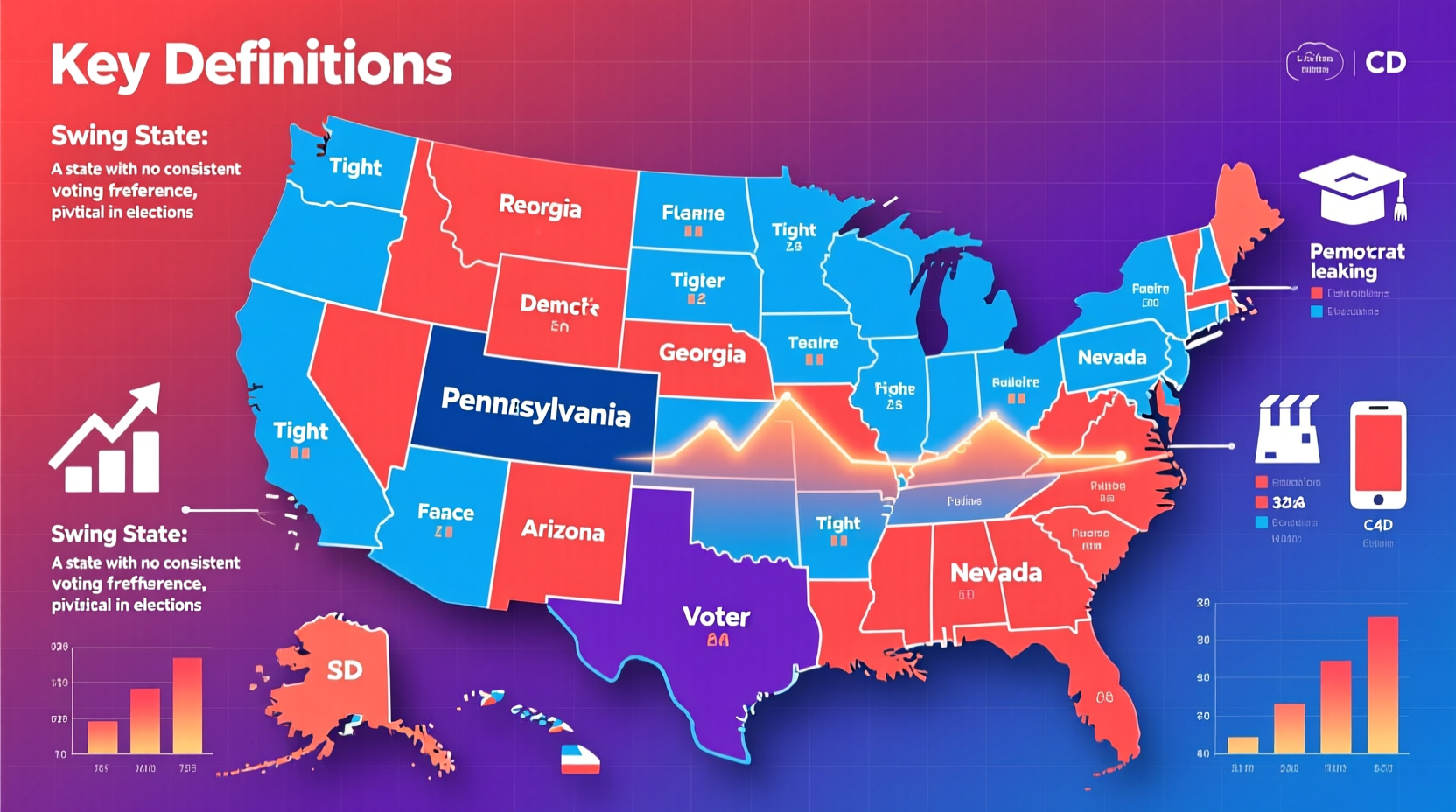

A “swing state” is any U.S. state where no single political party has overwhelming support, making it highly competitive during presidential elections. Unlike safe states—such as California (Democratic) or Oklahoma (Republican)—swing states lack consistent partisan dominance.

Common synonyms include:

- Battleground state: Emphasizes strategic focus by campaigns.

- Toss-up state: Indicates near-equal odds for either candidate.

- Marginal state: Reflects narrow margins of victory in past elections.

Swing states are not inherently neutral. Many have undergone long-term political shifts due to migration, generational change, or economic transformation. For example, Florida was reliably Democratic in the mid-20th century but now leans Republican, though still competitive. Arizona, once solidly red, has emerged as a swing state due to urban growth and demographic diversification.

“Swing states are laboratories of political change—they reflect broader societal transitions faster than stable states.” — Dr. Laura Chen, Political Geographer at Georgetown University

Key Factors That Turn States Into Swing States

No state is permanently destined to be a swing state. Shifts occur gradually through interrelated social, economic, and institutional forces. The following factors are central to understanding these transformations.

Demographic Change

Population composition is perhaps the most powerful driver of political change. When large numbers of people move into a state—or when birth rates shift among different groups—the electorate evolves.

- Migration from other states brings voters with different political preferences.

- Growing urban centers often lean liberal; expanding suburbs may tilt conservative or moderate.

- Increasing racial and ethnic diversity, particularly Latino, Asian American, and Black populations, reshapes voting patterns.

Economic Transformation

Industrial decline or technological growth alters voter priorities. A state dependent on manufacturing may shift left if union jobs disappear. Conversely, energy booms in oil-rich regions can strengthen Republican appeal.

Examples include Pennsylvania’s Rust Belt cities, where economic anxiety influenced 2016 and 2020 outcomes, and Colorado’s tech-driven economy attracting younger, educated professionals who favor Democrats.

Generational Replacement

As older, more conservative voters pass away and younger, more progressive cohorts reach voting age, state-level ideology can shift. This slow but steady process explains why Virginia transitioned from red to purple to blue over two decades.

Campaign Investment and Visibility

States don’t become swing states solely because of internal dynamics. They gain status when national campaigns pour money, advertising, and ground operations into them. Once candidates invest heavily, media attention follows, reinforcing the perception of competitiveness—even if underlying demographics haven't changed dramatically.

Electoral Rules and Voter Access

Voting laws significantly affect turnout and competition. States with early voting, mail-in ballots, and same-day registration tend to see higher participation, benefiting parties with broader coalitions. Restrictive laws may suppress turnout, narrowing the electorate and altering outcomes.

Historical Evolution: From Safe to Swing

Many current swing states were once predictable. Examining their evolution reveals how external pressures redefine political landscapes.

Case Study: Michigan

Middle of the 20th century: A Democratic stronghold due to strong labor unions and auto industry ties.

Late 20th century: Suburban growth and white flight diluted urban Democratic advantages.

2016: Donald Trump won by under 11,000 votes, breaking a decades-long Democratic streak.

2020: Joe Biden reclaimed it by 154,000 votes amid high minority turnout and pandemic concerns.

Michigan’s transformation reflects industrial decline, demographic aging, and suburban moderation—all amplifying its swing status.

Case Study: Georgia

For much of the 20th century, Georgia was solidly Democratic due to segregationist politics. After the Civil Rights Act, it shifted Republican. But rapid growth in Atlanta’s suburbs—home to college-educated whites and rising Black middle-class communities—created new fault lines.

In 2020, Joe Biden became the first Democrat to win Georgia since 1992. While Republicans regained ground in 2022 midterms, the state remains firmly in battleground territory due to mobilized minority voters and changing suburban attitudes.

Current Major Swing States and Trends (2020–2024)

| State | 2020 Margin | Key Demographics | Trend Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania | Biden +1.2% | Urban centers (Philadelphia, Pittsburgh), aging rural population | Slight Democratic edge, closely contested |

| Georgia | Biden +0.2% | Fast-growing metro Atlanta, high Black voter engagement | Emerging Democratic lean, but volatile |

| Arizona | Biden +0.3% | Suburban Phoenix, growing Latino electorate | Shifting left, but Republican base remains strong |

| Nevada | Biden +2.4% | Unionized service workers, diverse Las Vegas metro | Stable Democratic advantage recently |

| Wisconsin | Biden +0.6% | Rural-urban divide, moderate suburbs near Milwaukee | Highly competitive, slight Democratic momentum |

The table illustrates that while margins are narrow, the reasons for competitiveness vary widely. Nevada’s union strength contrasts with Arizona’s suburban realignment. Yet all share exposure to national messaging, heavy ad spending, and razor-thin results.

Actionable Checklist: How to Analyze a State’s Swing Potential

To predict whether a state might become a swing state—or remain one—use this checklist:

- Review recent election margins: Look at presidential and Senate races over the last three cycles. Are wins consistently within 5%?

- Analyze demographic data: Use Census Bureau reports to track migration, age distribution, and racial composition.

- Monitor voter registration trends: Is one party gaining active registrants faster than the other?

- Assess campaign activity: Are both parties opening field offices and airing ads?

- Track policy issues: Does the state face debates over healthcare, abortion, or energy that cut across party lines?

- Evaluate electoral reforms: Has voting access expanded or contracted recently?

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a deep-red or deep-blue state become a swing state?

Yes, though it takes time. States like Texas and California were once politically competitive. Texas has shown signs of becoming more competitive due to urban growth and demographic shifts, though it remains Republican-leaning. Long-term changes in education, income, and culture can erode partisan dominance.

Why do swing states get more attention during elections?

Because of the Electoral College system, winning a state—even by one vote—grants all its electoral votes (except in Maine and Nebraska). Candidates maximize impact by focusing resources where outcomes are uncertain. A $1 million ad buy in California yields little return for Republicans; the same investment in Wisconsin could sway tens of thousands of undecided voters.

Are swing states representative of the nation as a whole?

Not necessarily. Many swing states—like Wisconsin or Pennsylvania—are whiter and less urban than the country overall. Campaigns often tailor messages to these specific electorates, which can skew national discourse. Critics argue this gives disproportionate influence to a small subset of voters.

Conclusion: The Fluid Nature of Political Power

Swing states are not fixed entities but reflections of deeper currents in American society. Economic upheaval, demographic flows, and cultural realignment continuously redraw the electoral map. What defines a swing state today may not apply in a decade. Understanding these dynamics empowers citizens, analysts, and policymakers to anticipate change rather than react to it.

The rise and fall of swing states remind us that democracy is not static. It evolves with the people. Whether you're a voter, journalist, or strategist, recognizing the forces behind political competition allows for smarter engagement with the electoral process.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?