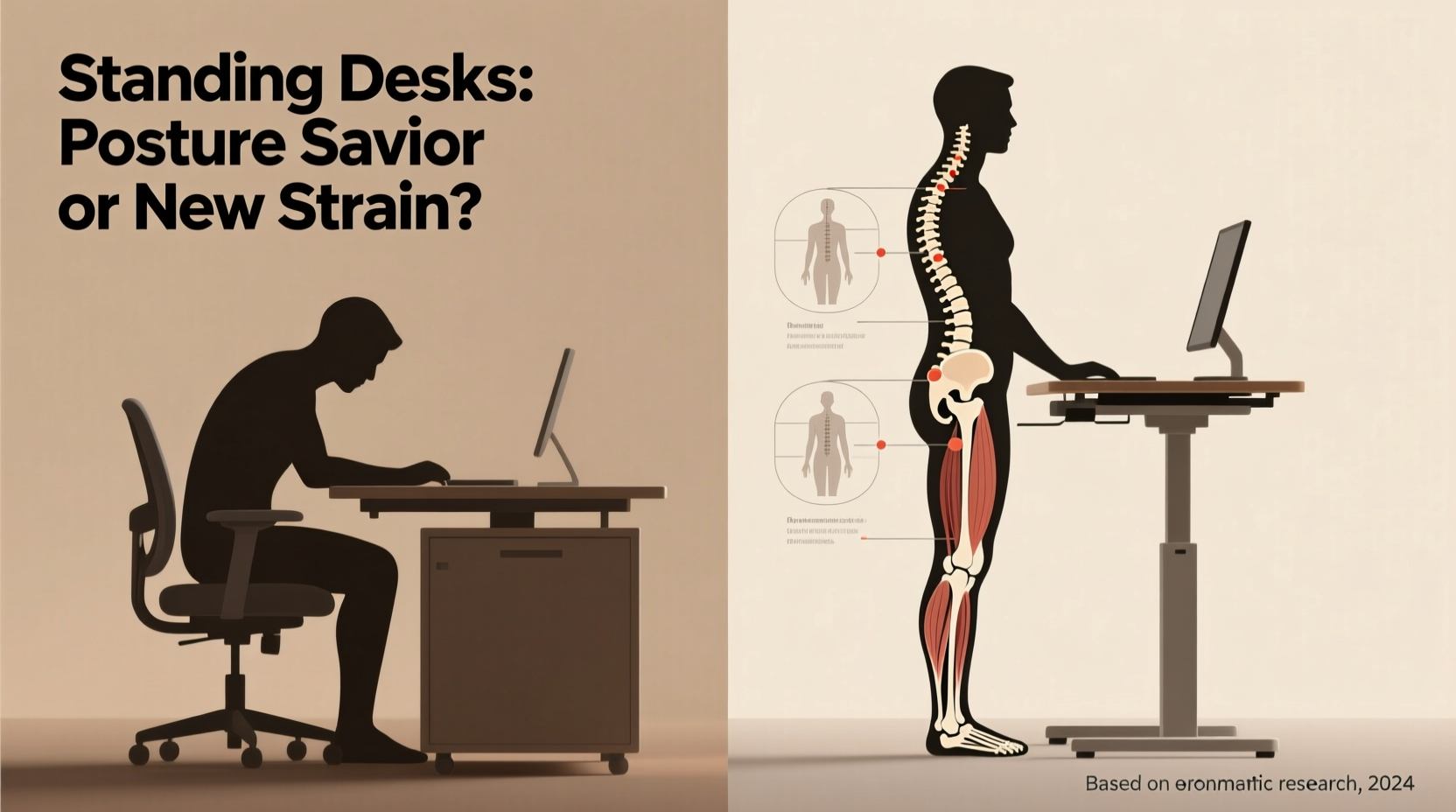

In an era where sedentary office work dominates daily life, standing desks have surged in popularity as a solution to poor posture, chronic back pain, and the broader health risks of prolonged sitting. Proponents claim they encourage better spinal alignment, reduce neck strain, and boost energy. But a growing number of users report new discomforts—aching feet, lower back stiffness, and even hip pain—raising a critical question: Are standing desks truly improving posture, or are they simply replacing one set of problems with another?

The truth lies somewhere in the middle. Standing desks aren’t inherently good or bad. Their impact depends on how they’re used, how long you stand, and whether proper ergonomics and movement habits are in place. This article examines the biomechanics of standing versus sitting, reviews clinical findings, and offers practical strategies to maximize benefits while avoiding common pitfalls.

The Posture Promise: Why Standing Desks Gained Popularity

For decades, research has linked prolonged sitting with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and musculoskeletal disorders. Office workers often spend 6–10 hours a day seated, frequently in suboptimal positions that encourage slouching, forward head posture, and rounded shoulders.

Standing desks emerged as a countermeasure. The idea is simple: standing engages core muscles, aligns the spine more naturally, and reduces the compressive forces on lumbar discs associated with sitting. Early adopters reported feeling more alert, experiencing less lower back fatigue, and adopting a more upright stance throughout the day.

A 2018 study published in Occupational Medicine found that participants using sit-stand desks reported a 32% reduction in upper back and neck pain after six weeks. Another review in the Journal of Physical Activity and Health noted improved posture metrics, including reduced forward head angle and thoracic kyphosis, among standing desk users.

“Alternating between sitting and standing helps prevent static loading on any one part of the spine.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Biomechanist and Ergonomics Consultant

Yet these benefits assume proper setup and usage. When misused, standing desks can introduce new postural stressors—especially if users stand rigidly for hours without support or movement.

The Hidden Risks: How Standing Can Harm Posture and Spine Health

Standing isn’t a neutral activity. It places different demands on the body than sitting, and improper standing mechanics can lead to new forms of strain. Common issues include:

- Lower back hyperextension: Leaning backward into the hips (a common “resting” stance) increases lumbar lordosis, stressing facet joints.

- Anterior pelvic tilt: Prolonged standing with locked knees shifts weight forward, tilting the pelvis and straining lower back muscles.

- Plantar fasciitis and foot fatigue: Hard flooring and lack of cushioning increase pressure on the feet, leading to compensatory postural changes.

- Shoulder elevation: If monitor height isn’t adjusted, users may hunch or raise shoulders, negating ergonomic gains.

Dr. Rajiv Mehta, a spine specialist at the Cleveland Clinic Spine Center, warns: “We’re seeing patients who swapped chronic sitting pain for chronic standing pain. They thought ‘standing is better,’ so they stood all day. But the body wasn’t designed for sustained static postures—whether sitting or standing.”

What the Research Says: Balancing the Evidence

Scientific consensus supports moderate use of standing desks—but not continuous standing. Key findings include:

- A 2021 Cochrane Review concluded that sit-stand desks reduce sitting time by about 30–60 minutes per day but found limited evidence for long-term pain reduction without behavioral support.

- A randomized trial in BMC Public Health showed that alternating 30 minutes sitting with 5–10 minutes standing significantly improved posture scores and reduced low back discomfort.

- However, a 2022 study in Ergonomics warned that standing longer than two hours continuously led to increased muscle fatigue in the lower limbs and altered spinal curvature.

The data suggests a Goldilocks zone: too much sitting is harmful, but so is too much standing. The optimal approach lies in frequent postural transitions and dynamic movement.

Do’s and Don’ts of Standing Desk Use

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Alternate sitting and standing every 30–60 minutes | Stand for more than 2 consecutive hours |

| Keep elbows at 90°, wrists neutral, screen at eye level | Hunch over a laptop placed too low |

| Wear supportive footwear or use an anti-fatigue mat | Stand barefoot on hard tile or concrete |

| Engage core lightly and keep weight balanced over feet | Lock knees or shift weight to one leg |

| Take micro-movements: shift weight, squat slightly, stretch | Remain completely still while standing |

A Real-World Example: From Back Pain to Balanced Posture

Samantha K., a software developer from Austin, switched to a standing desk after years of nagging lower back pain. Initially enthusiastic, she began standing 6–7 hours a day, believing more standing equaled better health. Within three weeks, her back pain returned—this time accompanied by sharp discomfort behind her knees and constant foot fatigue.

After consulting an occupational therapist, Samantha learned she was locking her knees and leaning backward to relieve pressure. Her workstation was also poorly configured: her monitor was too low, forcing her to look down and round her shoulders.

With adjustments—adding an anti-fatigue mat, raising her monitor, wearing supportive shoes, and following a 45/15 sit-stand ratio (45 minutes sitting, 15 standing)—her symptoms resolved within a month. “I didn’t realize I was just trading one bad habit for another,” she said. “Now I move more, stand smarter, and actually feel stronger.”

How to Use a Standing Desk Without Creating New Problems

To truly benefit from a standing desk, treat it as part of a dynamic workspace—not a replacement for sitting. Follow this step-by-step guide to integrate standing safely and effectively.

Step-by-Step Guide to Healthy Standing Desk Use

- Assess your current posture habits. Record yourself working for 10 minutes. Note slouching, head position, shoulder tension, and foot placement.

- Set up your desk correctly. Ensure your elbows are at 90°, wrists straight, and the top of your screen at or slightly below eye level.

- Start slow. Begin with 15–20 minutes of standing per hour during the first week. Increase by 5–10 minutes weekly until reaching a maximum of 2 hours total per day.

- Use an anti-fatigue mat. These mats encourage subtle muscle engagement and reduce pressure on joints.

- Wear supportive shoes or go barefoot on a cushioned surface. Avoid high heels or flat-soled shoes.

- Move intentionally. Shift your weight, perform calf raises, or do mini-squats every few minutes to promote circulation and reduce static load.

- Pair standing with movement breaks. Every hour, take a 2-minute walk or stretch session to reset posture and activate underused muscles.

Posture Checklist for Standing Desk Users

- ☑ Head aligned over shoulders, not jutting forward

- ☑ Shoulders relaxed, not hunched or elevated

- ☑ Elbows bent at 90°, close to the body

- ☑ Wrists neutral, not bent upward or downward

- ☑ Screen top at eye level

- ☑ Knees slightly bent, not locked

- ☑ Weight evenly distributed across both feet

- ☑ Pelvis neutral, not tilted forward or backward

- ☑ Feet flat, hip-width apart, optionally on a footrest

- ☑ Alternating with sitting every 30–60 minutes

FAQ: Common Questions About Standing Desks and Posture

Can standing desks fix bad posture?

Not on their own. Standing desks can support better posture when combined with proper ergonomics, regular movement, and postural awareness. However, they won’t correct long-standing muscular imbalances without targeted exercises and behavior change.

Is it better to sit or stand all day?

Neither. Continuous sitting or standing leads to postural fatigue. The ideal approach is variability—changing positions frequently to distribute mechanical load across different muscle groups and joints.

Why does my lower back hurt when I stand at my desk?

This is often due to hyperextending the lumbar spine (arching backward), locking the knees, or standing unevenly on one leg. Focus on maintaining a neutral pelvis, soft knees, and even weight distribution. An anti-fatigue mat and proper footwear can also help.

Conclusion: Movement Is the Real Solution

Standing desks are not a magic bullet for posture. They are tools—one piece of a larger strategy centered on movement, awareness, and ergonomic intelligence. Used wisely, they can reduce the harms of excessive sitting and encourage more dynamic work patterns. But when adopted without attention to form, duration, or individual biomechanics, they risk introducing new sources of discomfort.

The goal isn’t to stand more—it’s to move more. Whether sitting or standing, the key is variation. Your spine thrives on change, not static perfection. By combining adjustable workstations with intentional micro-movements, regular posture checks, and strength training, you can build resilience against both old and new back problems.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?