Peppers are among the most diverse and widely used ingredients in global cuisine, offering an expansive range of flavors, colors, shapes, and heat levels. From the mild sweetness of bell peppers to the searing intensity of the Carolina Reaper, understanding the differences between pepper varieties empowers cooks to make informed choices that elevate their dishes. Whether you're roasting, grilling, pickling, or seasoning, selecting the right pepper can transform a meal from ordinary to extraordinary. This comprehensive guide explores the most common and notable pepper types, organized by flavor, Scoville heat units, culinary function, and regional use—providing a practical reference for home cooks and culinary professionals alike.

Definition & Overview

Peppers, botanically classified under the genus Capsicum, are flowering plants in the nightshade family (Solanaceae). While often categorized as vegetables in cooking, they are technically fruits because they develop from the ovary of a flower and contain seeds. Originating in the Americas over 6,000 years ago, peppers were domesticated in Mesoamerica and South America before spreading globally via Spanish and Portuguese explorers in the 15th and 16th centuries. Today, they are integral to cuisines from Mexico to India, Thailand to Hungary.

The primary compound responsible for the heat in chili peppers is capsaicin, which stimulates nerve receptors in the mouth and skin, producing a burning sensation. However, not all peppers are hot—many, like bell and pimento peppers, have been selectively bred to eliminate capsaicin entirely, emphasizing sweetness and texture instead. Peppers vary dramatically in size, color (green, red, yellow, orange, purple, brown), shape (blocky, elongated, conical), and maturity level, all influencing flavor and application.

Key Characteristics

Understanding peppers requires attention to several key attributes:

- Heat Level: Measured on the Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) scale, ranging from 0 SHU (bell peppers) to over 2 million SHU (pepper spray-grade extracts).

- Flavor Profile: Ranges from grassy and vegetal (unripe green peppers) to fruity, smoky, or floral (ripe red or specialty chilies).

- Aroma: Fresh, earthy, floral, or roasted, depending on preparation and variety.

- Color & Form: Influences both visual appeal and nutrient content; red peppers, for example, contain more vitamin C and beta-carotene than green ones.

- Culinary Function: Used as a base ingredient (e.g., in sofrito), seasoning (dried powders), condiment (hot sauces), or garnish.

- Shelf Life: Fresh peppers last 7–14 days refrigerated; dried forms can last up to a year when stored properly.

Pro Tip: Heat is concentrated in the pepper’s placenta (the white inner ribs) and seeds. Remove these parts to reduce spiciness without sacrificing flavor.

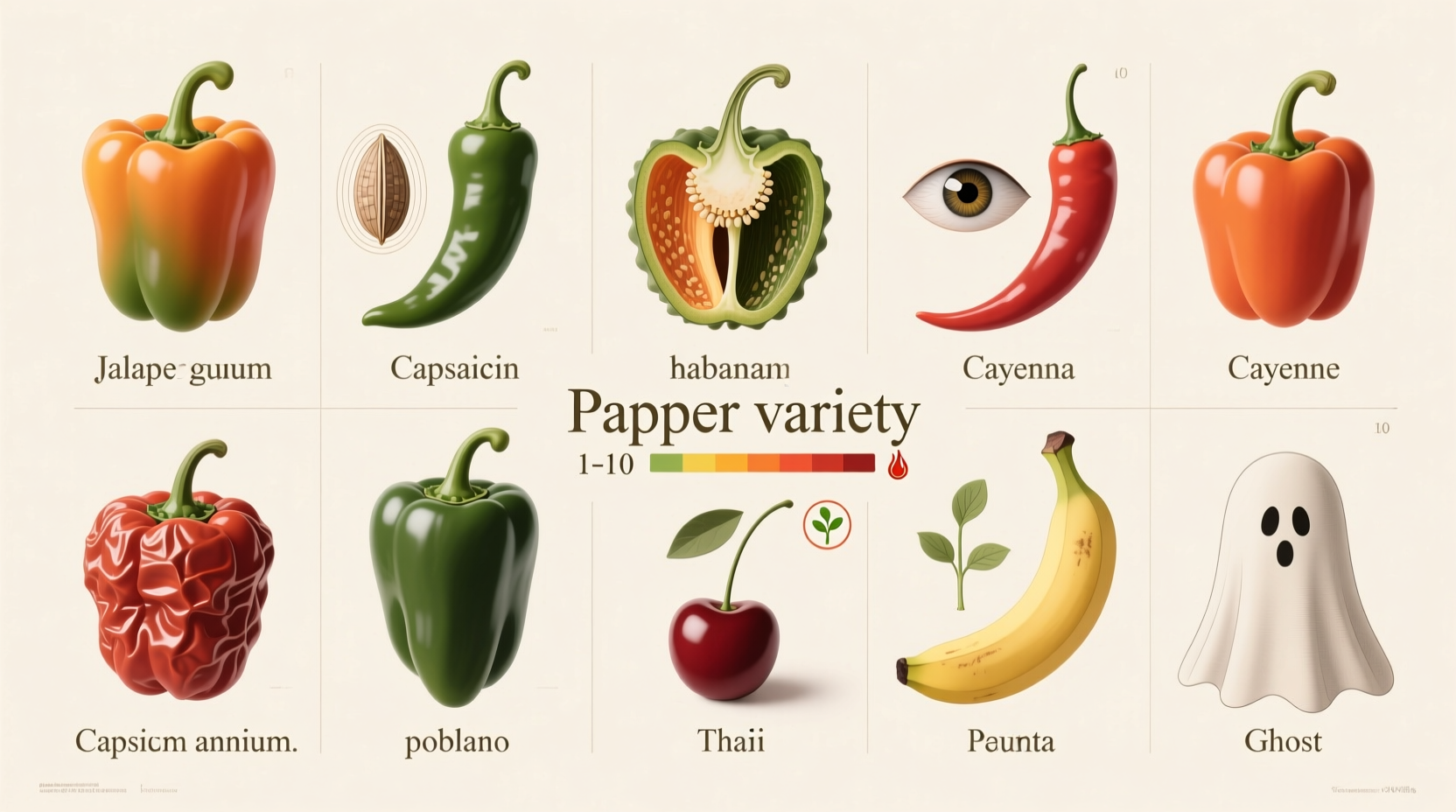

Variants & Types

With hundreds of cultivated varieties, peppers fall into several species, the most common being Capsicum annuum, C. chinense, C. frutescens, C. baccatum, and C. pubescens. Below is a curated list of 18 essential peppers, grouped by heat level and culinary utility.

Mild Peppers (0–500 SHU)

- Bell Pepper (Capsicum annuum): Sweet, crisp, and available in red, yellow, orange, green, and purple. Ideal for raw applications, roasting, stuffing, and stir-fries. Green bells are less sweet and slightly bitter; red, yellow, and orange are riper and sweeter.

- Pimento (aka Pimiento): Heart-shaped, glossy red, and extremely mild with a juicy, sweet flesh. Commonly found in jars, stuffed into olives, or used in pimento cheese.

- Cubanelle: Light yellow-green to red, long and tapered. Thin-walled and sweet, excellent for frying, sautéing, or adding to sandwiches and stews.

- Pepperoncini (Greek Hot): Often pickled, these pale yellow-green peppers offer a tangy, mildly spicy bite (100–500 SHU). Common in salads, sandwiches, and antipasti platters.

Medium-Hot Peppers (1,000–30,000 SHU)

- Jalapeño (C. annuum): Iconic green or red chili from Mexico, ranging 2,500–8,000 SHU. Earthy, bright, and moderately spicy. Used fresh in salsas, pickled, smoked (as chipotle), or stuffed.

- Serrano: Smaller and hotter than jalapeños (10,000–23,000 SHU), with a crisp, sharp bite. Frequently used in pico de gallo and fresh hot sauces.

- Fresno: Resembles a small red jalapeño, with a similar heat range (2,500–10,000 SHU) but fruitier flavor. Excellent for salsas, garnishes, and roasting.

- Cherry Pepper: Round and red, mild to medium heat. Often pickled or stuffed with cheese or meat.

- Anaheim (Long Green): Mild when green (500–2,500 SHU), slightly hotter when red. Roasted and peeled, it's a staple in Southwestern U.S. cuisine—used in chiles rellenos and green sauces.

- Poblano: Large, dark green, heart-shaped. Mild (1,000–2,000 SHU) with an earthy depth. When dried, it becomes ancho chili powder—a cornerstone of mole sauces.

- Guajillo: Dried form of a mild-to-medium chili, 2,500–5,000 SHU. Offers notes of berry, tea, and tang. Rehydrated and blended into sauces or marinades.

Hot to Extremely Hot Peppers (30,000+ SHU)

- Habanero (C. chinense): Lantern-shaped, typically orange or red, 100,000–350,000 SHU. Intensely fruity and floral with a searing finish. Central to Caribbean and Yucatán cuisine. Use sparingly in salsas, marinades, or hot sauces.

- Scotch Bonnet: Similar to habanero in heat and flavor but with a distinct bonnet shape. Predominant in Jamaican jerk seasoning and West African cooking.

- Thai Bird’s Eye Chili (Prik Kee Noo): Tiny but potent (50,000–100,000 SHU). Sharp, citrusy heat. Essential in Thai curries, stir-fries, and dipping sauces.

- Cayenne: Long, slender, and fiery (30,000–50,000 SHU). Often dried and ground into powder. Adds heat and color to soups, stews, and spice blends like Cajun seasoning.

- Tabasco: Small, thin, and red, used in the famous Tabasco sauce. Fermented with vinegar for a sharp, vinegary heat (30,000–50,000 SHU).

- Ghost Pepper (Bhut Jolokia): One of the first officially recognized superhots (800,000–1,041,427 SHU). Smoky and floral initially, then intensely painful. Used in extreme hot sauces and competitive eating.

- Carolina Reaper: Currently holds the Guinness World Record for hottest pepper (average 1,641,183 SHU, peaks over 2.2 million). Developed in South Carolina, it has a sweet, fruity start followed by overwhelming heat. Handle with gloves and use only in minute quantities.

- Trinidad Moruga Scorpion: Comparable to the Reaper in heat (up to 2 million SHU), with a complex, floral profile. Not for casual use—strictly for heat enthusiasts and commercial hot sauce production.

Comparison with Similar Ingredients

Peppers are frequently confused with other pungent ingredients. Understanding distinctions ensures proper usage.

| Pepper Type | Confused With | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) | Chili peppers | Not a Capsicum; derived from peppercorn berries. Heat is sharp and fleeting, not sustained. Used universally as a seasoning, not a vegetable. |

| Paprika | Red chili powder | Paprika can be sweet, smoked, or hot; made from ground capsicum. Indian chili powder often includes additional spices like cumin and coriander. |

| Peppadew | Pimento or cherry pepper | Commercial hybrid from South Africa, sweet-tart with moderate heat (500–700 SHU). Typically brined and sold in jars. |

| Pepperoncini | Jalapeño | Much milder, tangier due to pickling. Botanically a different cultivar of Capsicum annuum. |

\"The difference between a good dish and a great one often comes down to choosing the right pepper—not just for heat, but for aroma, color, and depth.\" — Chef Elena Ruiz, James Beard Finalist for Latin Cuisine

Practical Usage: How to Use Peppers in Cooking

Peppers serve multiple roles in the kitchen, from foundational aromatics to finishing accents. Their application depends on form (fresh, dried, smoked, powdered) and heat level.

Raw Applications

Use mild to medium-hot peppers raw to preserve crunch and brightness. Bell peppers add color and sweetness to salads, grain bowls, and crudités. Jalapeños and serranos enhance salsas, guacamole, and ceviche. For balanced heat, finely mince and mix into dressings or compound butter.

Cooked & Roasted

Roasting transforms peppers by caramelizing natural sugars and softening texture. Char poblano, Anaheim, or bell peppers over flame or under a broiler, then steam in a covered bowl before peeling. Roasted peppers enrich sauces, sandwiches (like Catalan romesco), and pasta dishes.

Dried & Ground

Drying concentrates flavor and extends shelf life. Ancho (dried poblano), guajillo, and pasilla are staples in Mexican moles. Crush or grind dried chilies into powders for rubs, soups, or adobo pastes. Toast lightly in a dry pan before use to unlock deeper aromas.

Smoked Varieties

Smoking imparts a rich, campfire-like complexity. Chipotle peppers (smoked jalapeños) lend depth to bean dishes, barbecue sauces, and braises. Smoked paprika (pimentón) is essential in Spanish chorizo and paella.

Preserved Forms

Peppers preserved in vinegar, oil, or brine offer tang and convenience. Pickled jalapeños top nachos and tacos. Pepperoncini brighten Mediterranean mezze plates. Fermented peppers, like those in gochujang or sriracha, develop umami and acidity over time.

Cooking Tip: Always taste a small piece of a new chili variety before adding it to a dish. Heat can vary significantly even within the same type due to growing conditions.

Pairing Suggestions & Culinary Ratios

Successful pepper use relies on balance. Consider these pairings:

- Sweet + Heat: Pair mango or pineapple with habanero for tropical salsas.

- Creamy + Spicy: Cool goat cheese or avocado with sliced serrano.

- Smoky + Tangy: Combine chipotle in adobo with lime juice and honey for glazes.

- Umami + Fire: Add gochugaru (Korean chili flakes) to kimchi or ramen broth.

General Ratio Guidelines:

- For salsas: 1 small habanero per 4 cups of tomatoes.

- For spice rubs: 1–2 tsp cayenne per pound of meat.

- For hot sauces: Start with 1–2 oz fresh chilies per cup of vinegar, adjust to taste.

- For roasting: 3–4 bell peppers serve 4 people as a side.

Storage & Shelf Life

Proper storage preserves flavor and prevents spoilage.

- Fresh Peppers: Store unwashed in the crisper drawer for up to 2 weeks. Avoid sealing in plastic without airflow.

- Whole Dried Chilies: Keep in airtight containers away from light and moisture for up to 1 year. Discard if brittle or odorless.

- Ground Spices: Lose potency after 6 months. Label with purchase date.

- Homemade Hot Sauce: Refrigerate and consume within 3–4 weeks unless fermented or properly canned.

- Freezing: Whole or chopped peppers freeze well for 6–12 months. Blanching not required, though texture may soften upon thawing.

Substitutions & Alternatives

When a specific pepper isn’t available, consider these swaps:

| Original Pepper | Best Substitute | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Jalapeño | Serrano (use less) or Cubanelle (for mild) | Serrano is hotter; reduce quantity by half. |

| Habanero | Scotch Bonnet or 1/4 tsp cayenne + pinch of apricot | For fruitiness, add dried apricot to the dish. |

| Ancho Chili | Guajillo or smoked paprika + bell pepper | Guajillo is tangier; smoked paprika adds depth. |

| Fresno | Red jalapeño or small bell pepper + cayenne | Adjust heat accordingly. |

Practical Tips & FAQs

How do I handle extremely hot peppers safely?

Wear nitrile gloves when cutting superhots like ghost peppers or Carolina Reapers. Avoid touching your face, especially eyes. Clean knives, cutting boards, and surfaces immediately with soapy water.

Why do some peppers turn red as they ripen?

Like tomatoes, peppers undergo chlorophyll breakdown and carotenoid development as they mature. Red peppers are sweeter, higher in nutrients, and often more expensive due to longer growing time.

Can I grow my own peppers at home?

Yes. Most peppers thrive in warm, sunny locations with well-drained soil. Start seeds indoors 8–10 weeks before the last frost. Provide consistent watering and support for heavy fruit.

What is the best way to reduce pepper heat in a dish?

Add dairy (yogurt, sour cream), acid (lime juice, vinegar), or sweetness (honey, sugar). Dilution with more non-spicy ingredients also helps. Note: Water spreads capsaicin rather than neutralizing it.

Are ornamental peppers edible?

Most are technically edible but bred for looks, not flavor. They can be extremely hot and lack culinary nuance. Avoid unless explicitly labeled for consumption.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Peppers are far more than sources of heat—they are nuanced ingredients that contribute color, aroma, sweetness, and depth to dishes across cultures. Mastery begins with understanding the spectrum from mild bell peppers to blistering superhots, each serving a distinct culinary purpose. Key points to remember:

- Heat is measured in Scoville Units, but flavor complexity matters just as much.

- Fresh, dried, smoked, and pickled forms offer vastly different applications.

- Removing seeds and membranes reduces heat without eliminating flavor.

- Proper storage extends usability and preserves potency.

- Substitutions are possible but require attention to flavor and heat balance.

Final Thought: Keep a pepper journal. Note varieties used, heat levels, pairings, and results. Over time, you’ll develop an intuitive sense for which pepper belongs in every dish.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?