For generations, stews and soups have nourished families across continents, appearing in nearly every global cuisine with regional variations that reflect local ingredients and traditions. Yet despite their shared purpose—warmth, comfort, and sustenance—the distinction between stew and soup is often blurred in everyday conversation. Many assume they are interchangeable, using the terms loosely based on appearance alone. In reality, these two preparations differ fundamentally in structure, technique, ingredient ratios, and culinary intent. Understanding these differences isn’t merely academic; it empowers home cooks to execute dishes with greater precision, achieve desired textures, and choose the right method for the meal at hand. Whether you're planning a weeknight dinner or refining your slow-cooked repertoire, knowing when to make a stew versus a soup can elevate your results from acceptable to exceptional.

Definition & Overview

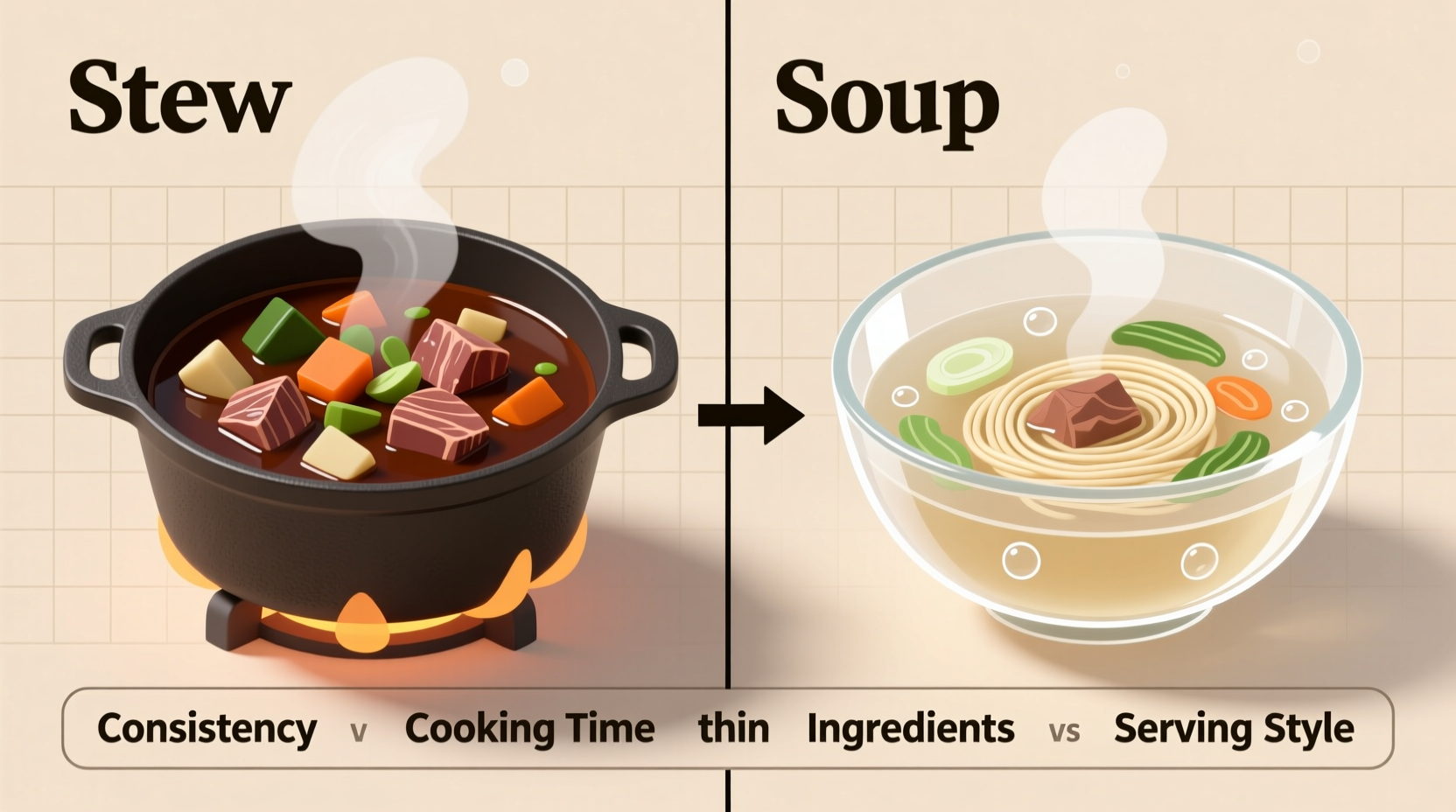

Soup is a liquid-based dish typically made by simmering ingredients—such as vegetables, meat, poultry, seafood, legumes, or grains—in water or stock. The resulting broth forms the primary component of the dish, carrying flavor, aroma, and nutrients. Soups vary widely in consistency, ranging from thin and brothy (like consommé) to thick and creamy (such as chowder), but they all prioritize fluidity and drinkability.

Stew, by contrast, is a more concentrated preparation where solid ingredients—especially meats and hearty vegetables—are cooked slowly in a small amount of liquid until tender. Unlike soup, the liquid in a stew acts primarily as a medium for heat transfer and flavor infusion rather than the main element. As a result, stews develop rich, dense textures and are usually served with minimal free-flowing liquid, often accompanied by starches like potatoes, dumplings, or bread to absorb the savory juices.

The divergence begins not just in outcome but in philosophy: soup celebrates liquidity and balance; stew emphasizes substance and depth. This foundational difference shapes everything from ingredient selection to cooking time and serving style.

Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Soup | Stew |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-to-solid ratio | High – mostly broth | Low – solids dominate |

| Texture | Thin to moderately thick | Dense, chunky, cohesive |

| Cooking time | Short to moderate (15 min–2 hrs) | Long (2–6+ hours) |

| Primary function of liquid | Edible base | Cooking medium, reduced glaze |

| Thickening agents | Roux, cream, purees, cornstarch | Natural gelatin, reduction, flour-dredged meat |

| Serving vessel | Bowl or cup | Deep plate or bowl, often without spoon depth |

| Typical proteins | Pre-cooked, delicate (chicken, fish, shellfish) | Tough cuts requiring braising (beef chuck, lamb shoulder) |

Practical Usage: How to Use Each Method

Choosing between stew and soup depends on available ingredients, desired meal profile, and time constraints. Each method serves distinct roles in kitchen practice.

Soup: Versatility and Speed

Soups excel in quick meals, detox regimens, appetizers, and light lunches. A clear chicken noodle soup can be assembled in under an hour using pre-cooked poultry and fresh vegetables. Cream-based soups like broccoli cheddar rely on roux or pureeing to build body while maintaining pourable consistency.

To prepare a standard vegetable soup:

- Sauté onions, carrots, and celery in olive oil until softened.

- Add garlic, herbs (thyme, bay leaf), and chopped tomatoes.

- Pour in 6–8 cups of vegetable or chicken stock.

- Add diced potatoes, green beans, zucchini, and simmer 20–30 minutes.

- Season with salt, pepper, and lemon juice before serving.

This approach yields approximately four servings of brothy, hydrating soup ideal for cooling temperatures or convalescence. For heartier versions, add beans or pasta—but take care not to overcook, which leads to mushiness.

Stew: Depth Through Time

Stewing transforms tough, collagen-rich meats into fork-tender morsels through prolonged exposure to moist heat. The process breaks down connective tissue into gelatin, enriching the sauce naturally. Unlike soups, stews rarely require added thickeners because the meat and root vegetables release enough starch and protein during cooking.

A classic beef stew follows this sequence:

- Cut beef chuck into 1.5-inch cubes and season with salt and pepper.

- Dredge lightly in flour and brown thoroughly in batches in a heavy pot.

- Remove meat, sauté onions, carrots, and garlic until fragrant.

- Return meat, add tomato paste, deglaze with red wine, then cover with beef stock (just below the surface of solids).

- Cover and simmer gently for 2.5–3.5 hours, adding parsnips and turnips in the final 45 minutes.

- Finish with fresh parsley and adjust seasoning.

The finished dish should hold its shape when scooped—a mass of meat and vegetables bound by a glossy, unctuous sauce—not float in a pool of liquid.

Pro Tip: Always brown meat in batches when making stew. Overcrowding lowers pan temperature, causing steaming instead of searing, which diminishes flavor development via the Maillard reaction.

Variants & Types

Both soups and stews span a broad spectrum of styles, reflecting cultural preferences and seasonal availability.

Soup Varieties

- Clear Broths: Japanese miso, Vietnamese pho, Italian stracciatella—emphasize aromatic clarity and delicate balance.

- Cream Soups: French velouté, American clam chowder—thickened with roux, cream, or purée.

- Bisques: Shellfish-based, heavily creamed, and strained for silkiness.

- Chilled Soups: Gazpacho, vichyssoise—serve cold, often blended, emphasizing freshness.

- Grain & Legume-Based: Minestrone, lentil soup—feature substantial plant proteins and complex carbohydrates.

Stew Varieties

- Braised Meat Stews: French boeuf bourguignon, Moroccan tagine—slow-cooked with wine or spices.

- Curry Stews: Indian rajma, Thai green curry—spice-paste driven, often coconut milk-enriched.

- One-Pot Grain Stews: Jambalaya, pilaf-style dishes—where rice absorbs most of the liquid.

- Dried Bean Stews: Cassoulet, feijoada—centered on legumes with smoked meats.

- Vegetable-Only Stews: Ratatouille (when cooked down), Ethiopian atkilt wot—rely on caramelization and spice layers.

The choice of variant often hinges on protein type, fat content, and whether the goal is preservation (as in winter stews) or refreshment (as in summer soups).

Comparison with Similar Dishes

While stew and soup are frequently compared, confusion also arises between them and other moist-heat preparations like chili, casserole, and ragù. Clarifying these distinctions enhances culinary literacy.

| Dish Type | Similarities to Soup/Stew | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Chili | Chunky, meat-and-bean base, often spicy | No broth; thicker than soup, drier than stew; usually includes chili powder and no roux |

| Casserole | Oven-baked, contains meat/vegetables | Baked, often topped with crust or cheese; less liquid, structural integrity post-bake |

| Ragù | Slow-simmered meat sauce | Designed for pasta coating; finer chop, longer reduction, minimal free liquid |

| Braise | Same technique as stewing | Typically single large cut (e.g., short ribs); less chopped, more presentation-focused |

\"A stew should stand up to a fork, not flow around it.\" — Chef Yotam Ottolenghi

This quote underscores the textural expectation: stews are meant to be eaten with a utensil that lifts mass, whereas soups invite sipping or shallow spooning.

Practical Tips & FAQs

Q: Can a soup become a stew—or vice versa?

A: Yes, through manipulation of liquid volume and cooking time. Reducing a thick soup aggressively can yield a stew-like consistency. Conversely, adding broth to an overly dry stew can rescue it as a soup. However, the reverse transformation compromises authenticity—adding liquid late dilutes developed flavors, while reducing early may leave ingredients undercooked.

Q: Is chili a stew or a soup?

A: Chili occupies a middle ground. Traditional Texas chili contains no beans and very little liquid, aligning more with a ragù or dry stew. Bean-heavy versions resemble thick bean soups. Most modern interpretations fall closer to stew due to low broth levels and emphasis on solid components.

Q: Do stews need a lid while cooking?

A: It depends on the desired outcome. Covered cooking retains moisture and speeds tenderness but limits evaporation. Uncovered cooking promotes reduction and sauce concentration. For best results, start covered, then uncover in the final 30–60 minutes to tighten the sauce.

Q: How long do soups and stews keep in the fridge?

A: Properly stored in airtight containers, soups last 3–4 days; stews 4–5 days due to lower water activity and higher fat content, which inhibit bacterial growth. Both freeze well for up to 3 months. Cool quickly before refrigerating to prevent condensation and texture degradation.

Q: What’s the best way to reheat a stew without drying it out?

A: Reheat gently over low heat on the stovetop, adding a splash of broth or water to restore moisture. Microwave reheating risks uneven heating and rubbery meat. Stir occasionally and cover partially to retain steam.

Q: Are there vegetarian stews?

A: Absolutely. Dishes like Provencal ratatouille (when fully reduced), Ethiopian shiro wat, or Spanish pisto qualify as stews when prepared with minimal liquid and maximum vegetable density. Mushrooms, eggplant, and lentils provide the necessary heft.

Storage Tip: Label frozen soups and stews with date and contents. Use quart-sized freezer bags laid flat—they thaw faster and save space.

Expert Insight: Texture as Identity

In professional kitchens, the line between stew and soup is rarely debated because plating conventions make it obvious. A consommé arrives in a wide-rimmed cup; coq au vin comes on a plate with jus clinging to meat and vegetables. But at home, where terminology is looser, understanding texture as identity helps guide execution.

Consider this case study: Two cooks prepare “beef stew.” One adds 4 quarts of water to 2 pounds of beef and simmers for 2 hours. The result? A beef-flavored soup. The other uses 1.5 quarts of stock, browns the meat properly, and reduces the liquid significantly. The outcome is a true stew—rich, cohesive, deeply flavored. Same ingredients, different technique, divergent outcomes.

The lesson: Ratio and reduction define the category more than name.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The distinction between stew and soup lies not in ingredients but in proportion, method, and intention. Soup prioritizes liquid, offering hydration, warmth, and versatility across meals. Stew emphasizes solids, transforming humble ingredients into hearty, satisfying centerpieces through slow, deliberate cooking.

Key points to remember:

- Liquid ratio: Soup has more broth; stew uses just enough liquid to cook ingredients.

- Cooking duration: Stews require longer times to break down tough fibers; soups can be fast or slow depending on type.

- Texture goal: Soup should flow; stew should mound.

- Thickening: Soups often use external agents (roux, cream); stews rely on natural gelatin and reduction.

- Serving style: Soup is drunk or sipped; stew is eaten with a fork or deep spoon.

Mistaking one for the other won’t ruin a meal, but recognizing their unique strengths allows better menu planning, improved technique, and more consistent results. When building flavor from scratch, ask: Am I creating a beverage or a braise? The answer determines your next move.

Call to Action: Next time you’re tempted to call any hot dish “soup,” pause and assess the liquid level. If the spoon stands upright, you’ve likely made a stew.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?