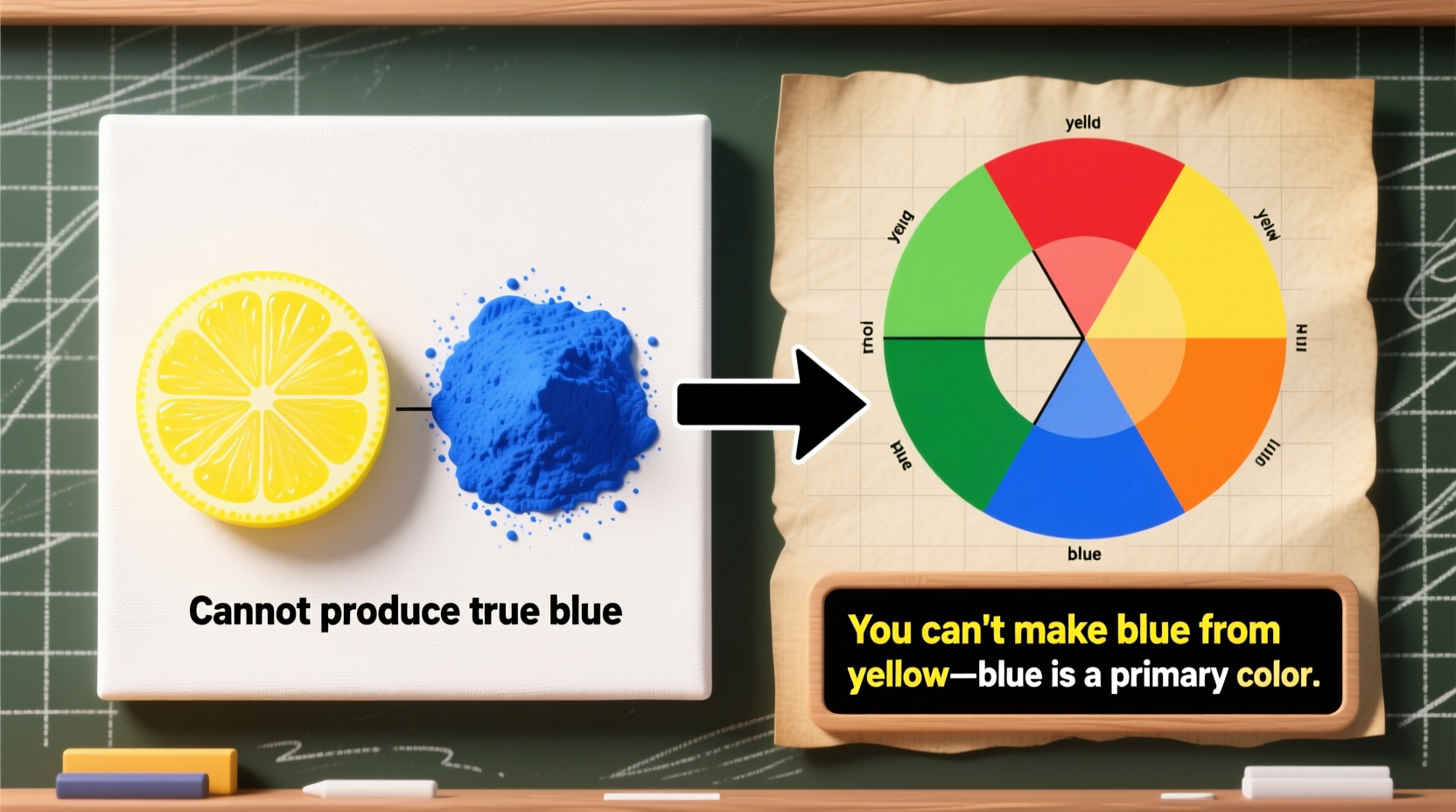

Color is more than just visual appeal—it’s science, perception, and craft combined. Whether you're painting, designing, or teaching art, knowing how colors interact is fundamental. One of the most common misconceptions in color theory is the belief that any color can be created by mixing two others. In particular, many beginners try to mix yellow and another color to produce blue, only to end up frustrated. The truth? You cannot make blue from yellow—and understanding why unlocks better results in your creative work.

The Science Behind Primary Colors

In traditional color theory, red, yellow, and blue are considered the primary colors. These are the foundational hues that cannot be created by mixing other colors together. Instead, they serve as the starting point for all other shades in the subtractive color model—the system used in painting, printing, and physical media where pigments absorb light.

When you mix two primary colors, you create a secondary color: orange (red + yellow), green (yellow + blue), and purple (blue + red). But because blue is a primary color, it cannot be synthesized by combining yellow with anything else. Yellow lacks the necessary wavelengths to generate the cool, short-wave frequencies associated with blue light and pigment.

“Primary colors exist because they represent irreducible points in human color perception. You can’t build a primary—you start with it.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Color Vision Researcher, University of Arts London

Why Mixing Yellow Never Produces Blue

At the core of this limitation lies both physics and biology. Human eyes perceive color based on how objects reflect or absorb different wavelengths of light. Blue pigments reflect short-wavelength light (around 450–495 nanometers), while yellow reflects longer wavelengths (570–590 nm). When you mix yellow paint into another color, you're adding compounds that reflect those longer wavelengths—not shorter ones.

No matter how much white, black, or green you add to yellow, you’re still working within the same reflective spectrum. Adding white creates lighter yellows or creams; black produces muddy olives or browns. Even blending yellow with green shifts toward chartreuse or lime, never toward azure or cobalt.

What to Do Instead: Practical Alternatives for Artists

Since you can't make blue from yellow, the solution isn’t persistence—it’s strategy. Here's how to work smarter with your materials and expectations.

Use the Right Starting Pigments

Always begin with a full set of primary colors. A well-stocked palette includes at least one reliable version of each: a true red (like cadmium red), a clean yellow (such as cadmium yellow), and a dependable blue (ultramarine or phthalo blue). This gives you control over every hue you’ll need.

Understand Color Bias in Paints

Not all blues or yellows are neutral. Some have warm undertones (leaning toward red or yellow), others cool (tending toward green or purple). For example:

- Cadmium yellow is warm and leans toward orange.

- Lemon yellow is cooler and mixes better with blues.

- Phthalo blue has a green bias, ideal for vibrant greens.

- Ultramarine blue leans toward purple, perfect for rich violets.

Knowing these biases helps you predict outcomes. Want a bright green? Mix lemon yellow with phthalo blue. Need a deep violet? Combine ultramarine blue with magenta, not cadmium red.

Create Depth Without Fabricating Blue

If you’re out of blue paint, don’t attempt alchemy—adjust your approach. Use available blues creatively:

- Thin layers with medium to suggest sky or water.

- Mix blue with complementary orange to create natural grays and shadows.

- Use temperature contrast: pair existing blue tones with warm yellows to enhance vibrancy through juxtaposition.

Step-by-Step Guide: Building an Efficient Mixing Strategy

- Assess your current palette. Identify which primaries you have and note their temperature biases.

- Test mixtures on scrap paper. Combine small amounts of yellow with various blues to see how green variations emerge.

- Avoid overmixing. Stir just enough to blend—excessive mixing can dull colors due to oxidation or filler dispersion.

- Label your custom blends. Save successful mixes (e.g., “Teal Base”) for future use.

- Stock reliable blue pigments. Keep at least two types: one green-biased, one red-biased, for maximum flexibility.

Common Misconceptions About Color Mixing

Beyond the myth of making blue from yellow, several other misunderstandings hinder artistic progress:

| Misconception | Reality |

|---|---|

| All primary colors can be mixed if you know the right formula. | No—primary colors are defined by their inability to be created through mixture. |

| Black can be made perfectly by mixing all three primaries. | Rarely true; most triad mixes yield dark brown. Pre-made black or near-black pigments perform better. |

| White paint makes colors brighter. | It tints them, reducing saturation. Brightness comes from pure pigment, not dilution. |

| More pigment always means stronger color. | Overloading paint can disrupt binding agents, leading to cracking or poor adhesion. |

Mini Case Study: The Classroom Experiment That Changed Everything

In a first-year art class at Portland Community College, students were asked to create a seascape using only yellow, red, and white. The goal was to expose limitations in intuitive mixing. Most tried desperately to generate blue tones, layering white over yellow-red mixes, hoping for turquoise. None succeeded. Afterward, the instructor introduced ultramarine blue and demonstrated how even a tiny amount transformed the scene.

The lesson stuck: creativity thrives within constraints, but technical accuracy requires proper tools. One student later said, “I wasted 40 minutes chasing a color that didn’t exist. Now I check my palette before I start.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Can digital tools make blue from yellow?

No—not in the way people think. On screens, color follows the additive model (RGB), where red, green, and blue light combine to form white. Yellow on screen is made from red and green light. While software lets you pick any hex code, you’re selecting predefined values, not chemically mixing pixels. So practically, you still rely on pre-existing blue channels.

If I mix yellow and blue, do I get green every time?

Mostly yes, but the result depends on pigment ratios and bias. A red-leaning blue (ultramarine) mixed with yellow yields a duller, olive-green. A green-leaning blue (phthalo) with lemon yellow produces a vivid emerald. Always test combinations first.

Are there any paints labeled 'blue' that aren’t actually blue?

Sometimes. Certain metallic or iridescent paints may appear blue under specific lighting but contain no blue pigment. Also, some \"convenience colors\" like teal or turquoise are pre-mixed and may skew unexpectedly when blended further. Read pigment labels (e.g., PB29 for ultramarine) to verify authenticity.

Checklist: Mastering Realistic Color Expectations

- ☑ Stock genuine blue pigments—don’t rely on improvisation.

- ☑ Learn the color bias of your yellows and blues.

- ☑ Test mixtures before applying to canvas.

- ☑ Use labeled swatches to document successful blends.

- ☑ Replace dried-out or contaminated paints promptly.

- ☑ Study the difference between additive (light) and subtractive (pigment) models.

- ☑ Teach others why blue cannot be derived from yellow.

Conclusion: Work With Color, Not Against It

Trying to make blue from yellow is like trying to grow apples from orange seeds—it violates the rules of the system. Accepting that some colors are foundational frees you to focus on what truly matters: skillful application, thoughtful composition, and intentional mixing. Respect the science behind the spectrum, and your artwork will gain clarity, depth, and authenticity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?