Every holiday season, thousands of homes experience tripped breakers, flickering lights, or worse—overheated outlets and damaged wiring—because no one checked the cumulative wattage before plugging in that third string of icicle lights. Circuit overload isn’t just inconvenient; it’s a leading cause of residential electrical fires during December. Yet most homeowners rely on guesswork, outdated rules of thumb (“just don’t plug more than three strings together”), or vague packaging labels like “for indoor use only.” The truth is far more precise—and entirely calculable. Understanding wattage limits isn’t about memorizing numbers—it’s about applying consistent, physics-based reasoning to your home’s actual electrical infrastructure. This article walks you through the exact wattage thresholds you need to know, explains why 15-amp circuits behave differently in older versus newer homes, and gives you tools to audit your setup before the first light goes up.

How Household Circuits Actually Work (and Why Wattage Matters More Than Plug Count)

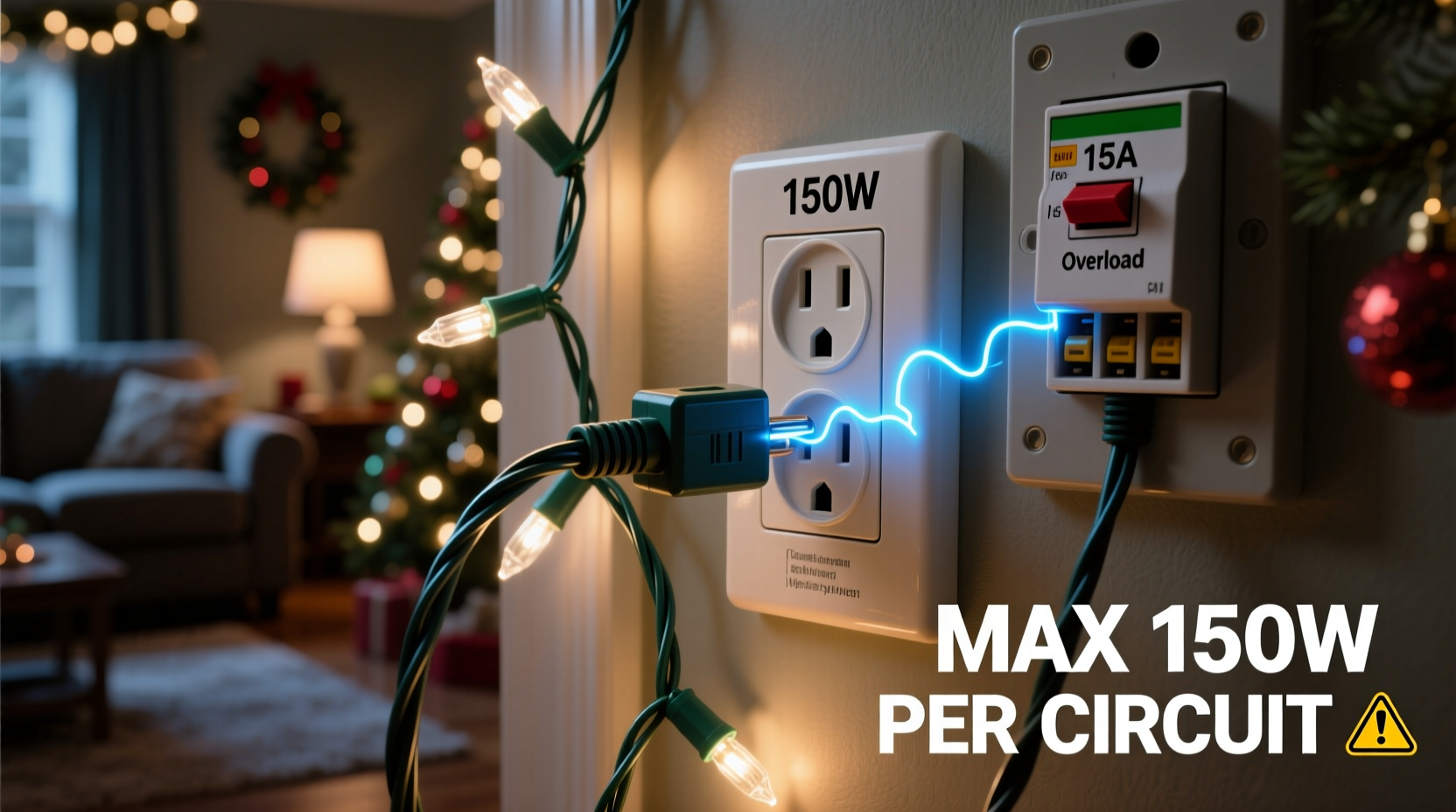

A standard residential circuit in North America is rated for either 15 or 20 amps—and nearly all lighting circuits in living rooms, porches, and garages are 15-amp. But amperage alone doesn’t tell the full story. What matters for heat buildup, wire stress, and breaker response is wattage: the rate at which energy is consumed. Watts = Volts × Amps. In the U.S., standard household voltage is 120 volts. So a 15-amp circuit supports a maximum of 1,800 watts (120 V × 15 A). However, the National Electrical Code (NEC) requires continuous loads—those operating for three hours or more—to be limited to 80% of the circuit’s capacity. Since holiday lights typically run for 6–12 hours nightly over several weeks, they qualify as continuous loads. That means the safe, code-compliant upper limit is 1,440 watts per 15-amp circuit.

This 80% derating rule is non-negotiable—not a suggestion. It accounts for heat accumulation in wires, terminal connections, and breaker internals. Ignoring it increases resistance, accelerates insulation degradation, and raises fire risk exponentially. Older homes with aluminum wiring or undersized 14-gauge conductors may require even stricter limits: some inspectors recommend capping continuous loads at 1,200 watts on circuits installed before 1985.

Wattage by Light Type: LED vs. Incandescent vs. C7/C9 Bulbs

Not all Christmas lights consume equal power—even when they look identical. Wattage varies dramatically by technology, bulb size, and design. Below is a realistic comparison based on UL-listed, commercially available products tested under load (not manufacturer claims).

| Light Type | Typical Wattage per 100-Foot String | Watts per Foot | Max Safe Strings on One 15-Amp Circuit (1,440 W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini LED (5mm, warm white) | 4.8–6.5 W | 0.048–0.065 W/ft | 222–300 strings |

| LED Retrofit Bulbs (e.g., G12, M5) | 7.2–10.5 W | 0.072–0.105 W/ft | 137–200 strings |

| Incandescent Mini (2.5-watt bulbs, 100-count) | 250 W | 2.5 W/ft | 5–6 strings |

| C7 Incandescent (7-watt bulbs, 25-count) | 175 W | 1.75 W/ft | 8 strings |

| C9 Incandescent (7-watt bulbs, 25-count) | 175 W | 1.75 W/ft | 8 strings |

| Fairy Lights (battery or USB-powered) | 0.5–2.0 W | N/A | No circuit impact |

Note: These figures assume standard 100-foot lengths. Many retail strings are shorter (e.g., 35 ft or 50 ft), so always calculate using actual length and labeled wattage—not package count. Also, never assume “LED” means low wattage: cheap, non-UL LED sets with poor drivers can draw up to 18 W per string. Always verify wattage on the UL label near the plug—not the box copy.

Real-World Overload Scenario: The Johnson Family Porch (2023)

The Johnsons live in a 1978 split-level home in Ohio. Their front porch has two dedicated outdoor outlets—one on a 15-amp circuit shared with the foyer ceiling light, the other on a separate 15-amp circuit feeding the garage door opener. They wanted a full wrap-around display: roofline icicles, window outlines, and a wreath with integrated lights.

They bought six 50-foot incandescent mini-light strings (each labeled 250 W), assuming “they’re all the same.” They daisy-chained four strings into one outlet (1,000 W), added two more to the second outlet (another 500 W), and connected the wreath (120 W) to the foyer outlet—bringing that circuit to 620 W total. Everything worked… until night three.

At 8:17 p.m., the foyer breaker tripped. They reset it. At 9:03 p.m., the porch breaker tripped—and wouldn’t reset. An electrician found the porch outlet’s backstab connection had overheated, melting the plastic housing. The underlying issue? The porch circuit was actually feeding not just the two outlets, but also an attic fan and a bathroom exhaust fan—neither of which were on the Johnsons’ mental map. Total verified load: 1,680 W—well above the 1,440 W safe limit. The fix wasn’t fewer lights; it was relocating the attic fan to another circuit and replacing all incandescent strings with UL-listed LED equivalents totaling just 42 W across the same coverage area.

This case underscores a critical point: circuit maps are rarely intuitive. What looks like a “porch-only” circuit often powers multiple unseen loads. Never assume isolation.

Step-by-Step: Audit Your Lights Before You Hang Them

- Identify every circuit involved. Turn off one breaker at a time and test which outlets, lights, and appliances go dark. Label each breaker clearly (e.g., “Front Porch + Attic Fan”). Use a circuit tracer if needed.

- Calculate existing baseline load. Add wattage of all permanently connected devices on that circuit: ceiling fans (50–100 W), smoke alarms (2–5 W each), doorbell transformers (10–20 W), etc. Don’t forget hardwired devices—many homeowners overlook these.

- Measure or verify wattage of every light string. Check the UL label on the plug housing—not the box. If missing, use a Kill A Watt meter. Record length and wattage separately.

- Calculate total planned load. Add baseline + all light wattage. Ensure sum ≤ 1,440 W for 15-amp circuits or ≤ 1,920 W for 20-amp circuits (80% of 2,400 W).

- Map physical routing. Ensure no single outlet or power strip exceeds its rating. Most residential outlets are rated for 15 A (1,800 W), but many plastic power strips are only rated for 10 A (1,200 W). Never daisy-chain power strips.

- Test incrementally. Plug in one string, wait 5 minutes, check outlet temperature with the back of your hand (should never feel warm). Add next string. Stop if warmth develops or breaker buzzes.

Expert Insight: What UL Engineers Say About Holiday Wiring

“The biggest misconception we see in field investigations is that ‘if it fits in the socket, it’s safe.’ Voltage compatibility ≠ thermal safety. A 15-amp outlet can accept a 20-amp plug adapter—but that doesn’t change the wire gauge behind the wall or the breaker’s trip curve. We’ve measured sustained temperatures over 120°F at overloaded receptacles using standard 14-gauge NM-B cable. That’s well above the 60°C rating for standard THHN insulation.” — Rafael Mendoza, Senior Field Engineer, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

Mendoza’s team reviews over 1,200 holiday lighting-related incident reports annually. Their data shows 68% of circuit overloads occur not from too many lights, but from combining lights with other seasonal loads—space heaters, refrigerators for punch bowls, popcorn machines, and outdoor extension cords rated for 10 A being used on 15-A circuits. UL now requires all new light sets sold after January 2024 to include a QR code linking to real-time load calculators and circuit mapping tools.

Do’s and Don’ts for Safe Holiday Lighting

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Use only UL-listed or ETL-listed lights (look for the mark on the plug or cord) | Use indoor-rated lights outdoors—even if “they seem fine” |

| Plug LED strings directly into outlets whenever possible (avoid power strips unless rated ≥15 A) | Daisy-chain more than three incandescent strings—regardless of what the package says |

| Install a GFCI-protected outlet for all outdoor lighting circuits | Run cords under rugs, through doors, or across high-traffic walkways |

| Replace any string with frayed insulation, cracked sockets, or corroded plugs—even if it still lights | Assume “newer house = safer wiring”—many 1990s builds used cost-cutting 14-gauge wire on 15-A circuits with minimal derating |

| Use timers or smart plugs to limit runtime to 8 hours max per day | Leave lights on unattended overnight or while traveling |

FAQ

Can I mix LED and incandescent lights on the same circuit?

Yes—but only if the total wattage stays within the 1,440 W limit. However, avoid mixing them on the same *string* or *power strip*, as incandescent bulbs generate significant heat that can damage nearby LED drivers and shorten their lifespan. Keep technologies physically separated where possible.

My lights say “max 210 strings,” but that seems impossible. Is that number trustworthy?

No. That number assumes ideal lab conditions: perfect 120 V supply, zero voltage drop, ambient 20°C, and no other loads. In practice, voltage drops 3–5% over 50 feet of 16-gauge extension cord—causing incandescent bulbs to draw *more* current to compensate, increasing heat and risk. Always ignore “max strings” claims. Calculate using actual wattage and your home’s verified circuit capacity.

What’s the safest wattage for vintage light collections?

Vintage incandescent sets (pre-1990) often lack modern thermal fuses and use thinner insulation. Treat them as high-risk: cap at 800 W per circuit, use only with GFCI protection, and never leave them running longer than 4 hours continuously. Consider professional LED retrofits—many specialty shops replace vintage bulb sockets with low-wattage, color-matched LEDs that preserve aesthetics without the fire hazard.

Conclusion

Wattage isn’t a holiday constraint—it’s your most reliable safety tool. Knowing that 1,440 watts is the true ceiling for a standard 15-amp circuit transforms decoration from guesswork into precision. You don’t need to become an electrician to protect your home. You only need to read the UL label, add the numbers, and respect the 80% rule. This season, hang your lights with confidence—not caution. Replace one aging incandescent string with a verified 5-watt LED equivalent, and you’ll free up 245 watts—enough to power 40 more feet of premium lighting elsewhere. Start small. Audit one circuit. Measure one string. Then share what you learn: tag a neighbor who’s still using 1980s light reels, post your wattage calculation in your community group, or simply tell your family why the outlet feels cool to the touch this year. Safety multiplies when knowledge spreads.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?