DNA is the blueprint of life, carrying the genetic instructions that govern the development, functioning, and reproduction of all known living organisms. At the heart of its remarkable functionality lies a deceptively simple yet profoundly important architectural detail: its two strands run in opposite directions. This arrangement—known as antiparallel orientation—is not arbitrary. It is a fundamental aspect of DNA’s double helix structure, playing a critical role in replication, protein binding, and overall molecular stability. Understanding why DNA strands are antiparallel provides insight into the elegance of biological design and the precision required for life to persist across generations.

The Antiparallel Nature of DNA: A Structural Overview

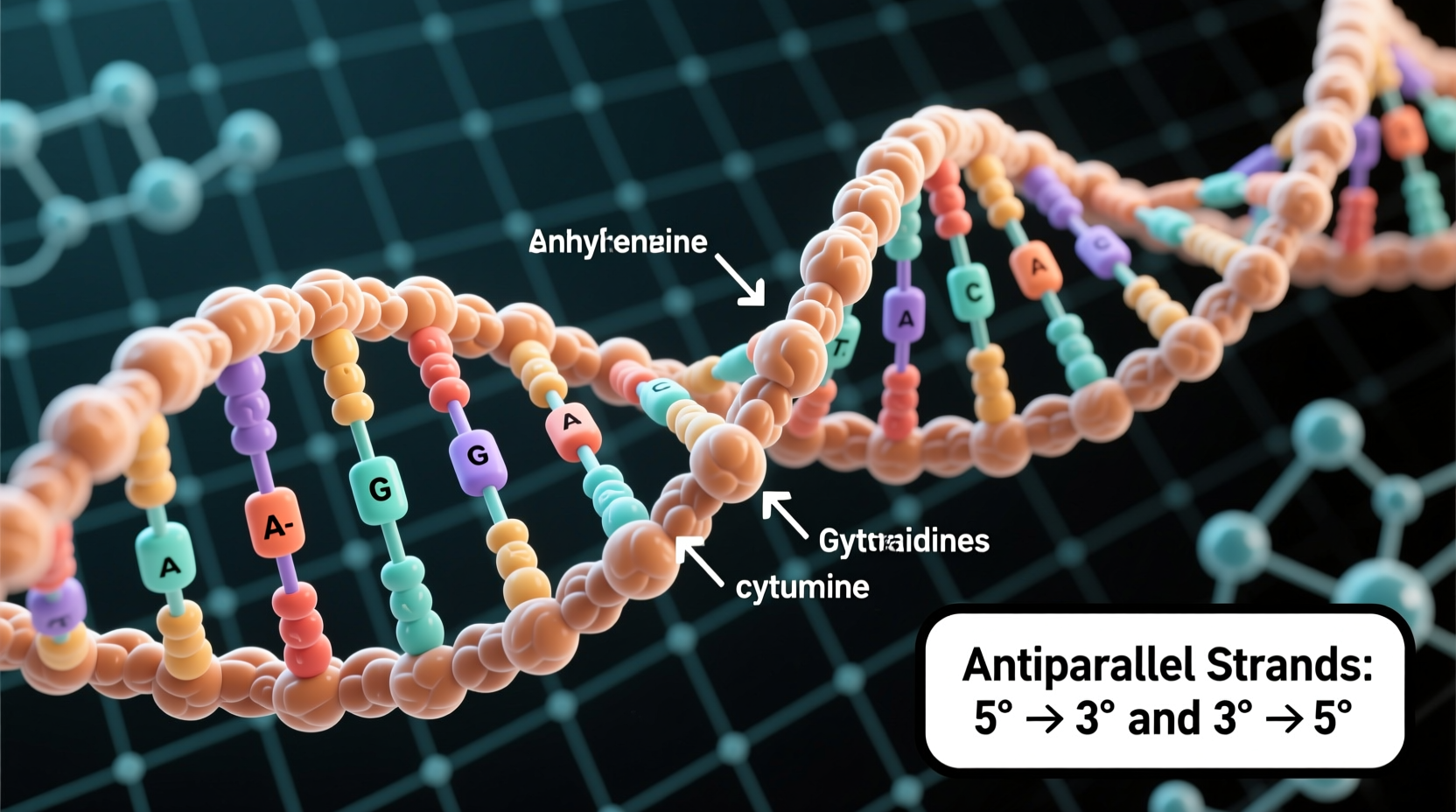

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick proposed the double helix model of DNA, revealing that the molecule consists of two polynucleotide chains twisted around each other. Each strand is composed of repeating units called nucleotides, which include a sugar (deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and one of four nitrogenous bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), or guanine (G). The two strands are held together by hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs—A with T, and C with G.

What makes the structure truly functional is the directional alignment of these strands. One strand runs in the 5' to 3' direction, meaning the phosphate group attaches to the 5' carbon of the sugar in one nucleotide and links to the 3' carbon of the next. The complementary strand runs in the opposite direction—3' to 5'. This opposing orientation defines the antiparallel nature of DNA.

Why Antiparallel? The Functional Advantages

The antiparallel configuration is not merely a structural curiosity—it enables essential biological processes. Without it, DNA replication and transcription would be inefficient or impossible.

One key reason for the antiparallel arrangement lies in enzyme compatibility. DNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing new DNA during replication, can only add nucleotides in the 5' to 3' direction. Because the template strands are antiparallel, replication proceeds differently on each strand: continuously on the leading strand and in short fragments (Okazaki fragments) on the lagging strand. This asymmetry is only possible because the strands run in opposite directions.

Moreover, the antiparallel layout ensures optimal base stacking and hydrogen bonding. The uniform width of the helix (approximately 2 nanometers) is maintained because purines (A and G) pair with pyrimidines (T and C), and the antiparallel orientation aligns the sugar-phosphate backbones symmetrically. This symmetry contributes to the stability of the helix and protects the genetic code within the core.

“DNA’s antiparallel structure is a masterstroke of molecular evolution—simple in design, profound in consequence.” — Dr. Helen Rostova, Molecular Biologist, MIT

Replication Mechanics: How Antiparallel Strands Shape the Process

DNA replication begins at specific sites called origins of replication, where the double helix is unwound by helicase enzymes. As the strands separate, they form a replication fork. Due to the antiparallel nature of the original duplex, the two new strands must be synthesized in different ways.

- Leading Strand: Synthesized continuously in the 5' to 3' direction, following the movement of the replication fork.

- Lagging Strand: Synthesized discontinuously in short segments, also in the 5' to 3' direction, but away from the fork. These segments are later joined by DNA ligase.

This difference arises directly from the antiparallel orientation. If both strands ran in the same direction, both could be replicated continuously—but biochemical constraints prevent polymerases from working in the 3' to 5' direction. Evolution has thus favored an elegant solution: allow one strand to be built smoothly and the other in pieces, all made possible by the opposing alignment of the templates.

Step-by-Step: DNA Replication in Antiparallel Context

- DNA helicase unwinds the double helix at the origin.

- Single-strand binding proteins stabilize the separated strands.

- Primase synthesizes RNA primers on both strands.

- DNA polymerase III adds nucleotides to the 3' end of the primer on the leading strand (continuous synthesis).

- On the lagging strand, multiple primers are laid down, and DNA polymerase III builds Okazaki fragments.

- DNA polymerase I replaces RNA primers with DNA.

- DNA ligase seals the nicks between fragments.

Evidence and Discovery: How We Know DNA Is Antiparallel

The antiparallel model was confirmed through a combination of X-ray crystallography, chemical labeling experiments, and enzymatic studies. Rosalind Franklin’s famous Photo 51 provided crucial evidence of the helical structure, including the uniform diameter that implied symmetrical base pairing. Later, biochemical assays using enzymes that recognize directional ends—such as kinases and phosphatases—confirmed the polarity of DNA strands.

In the 1960s, researchers used radioactive labeling to track the incorporation of nucleotides. They found that new DNA grew only in the 5' to 3' direction, supporting the idea that the template strands must be oriented oppositely to allow replication on both.

Common Misconceptions About DNA Directionality

Some learners assume that antiparallel means the strands are chemically different. In reality, both strands are made of the same type of nucleotides; the distinction lies solely in their orientation. Another misconception is that the antiparallel nature complicates replication unnecessarily. On the contrary, it allows for high fidelity and efficiency, given the directional constraints of existing enzymes.

It's also worth noting that while most DNA is antiparallel, certain synthetic or viral DNA forms (like some quadruplex structures) may deviate. However, in standard B-DNA—the predominant form in cells—antiparallel alignment is universal.

Practical Implications in Biotechnology and Medicine

Understanding antiparallel structure is vital in fields like genetic engineering, PCR (polymerase chain reaction), and CRISPR gene editing. For example, PCR relies on primers designed to bind in opposite directions on complementary strands—only possible because the target DNA is antiparallel. Similarly, antisense therapy uses synthetic strands that bind to mRNA in an antiparallel fashion to block gene expression.

Table: Antiparallel DNA – Key Features and Functions

| Feature | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Strand Orientation | One strand 5'→3', the other 3'→5' | Enables directional synthesis by DNA polymerase |

| Base Pairing | A-T and C-G with consistent spacing | Maintains uniform helix width and stability |

| Replication Mechanism | Leading and lagging strand synthesis | Allows simultaneous copying of both templates |

| Enzyme Compatibility | DNA polymerase works 5'→3' | Ensures accurate proofreading and repair |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can DNA strands ever be parallel?

In nature, standard double-stranded DNA is always antiparallel. While synthetic parallel DNA duplexes have been created in labs under special conditions, they are unstable and non-functional in biological systems.

How does antiparallel structure affect mutations?

The structure itself doesn’t cause mutations, but it influences how errors are detected and repaired. Mismatch repair enzymes use strand directionality (via methylation markers in bacteria) to identify which strand is the original template and which contains the error.

Is RNA also antiparallel when it binds to DNA?

Yes. During transcription, RNA polymerase reads the DNA template in the 3'→5' direction and synthesizes RNA in the 5'→3' direction. The resulting RNA-DNA hybrid is temporarily antiparallel, ensuring accurate transcription.

Conclusion: Embracing the Elegance of Molecular Design

The antiparallel arrangement of DNA strands is a cornerstone of molecular biology. Far from being a trivial detail, it underpins the mechanisms of heredity, enables precise replication, and supports the complexity of life. From the elegance of base pairing to the choreography of replication enzymes, every aspect of DNA function is shaped by this directional duality.

As we continue to explore genetics, synthetic biology, and personalized medicine, a deep appreciation for foundational concepts like antiparallelism becomes increasingly valuable. Whether you're a student, researcher, or simply curious about life at the molecular level, recognizing the significance of DNA’s architecture opens the door to greater understanding.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?