Life on Earth spans an astonishing range of complexity—from single-celled bacteria to intricate multicellular organisms like humans. At the heart of this biological diversity lies a fundamental truth: not all cells are the same. The existence of different cell types is not random but a highly evolved strategy that enables organisms to perform specialized tasks efficiently, adapt to environments, and sustain life in increasingly complex forms. Understanding why cell diversity exists reveals insights into biology’s most elegant mechanisms—differentiation, evolution, and functional specialization.

The Foundation of Cellular Specialization

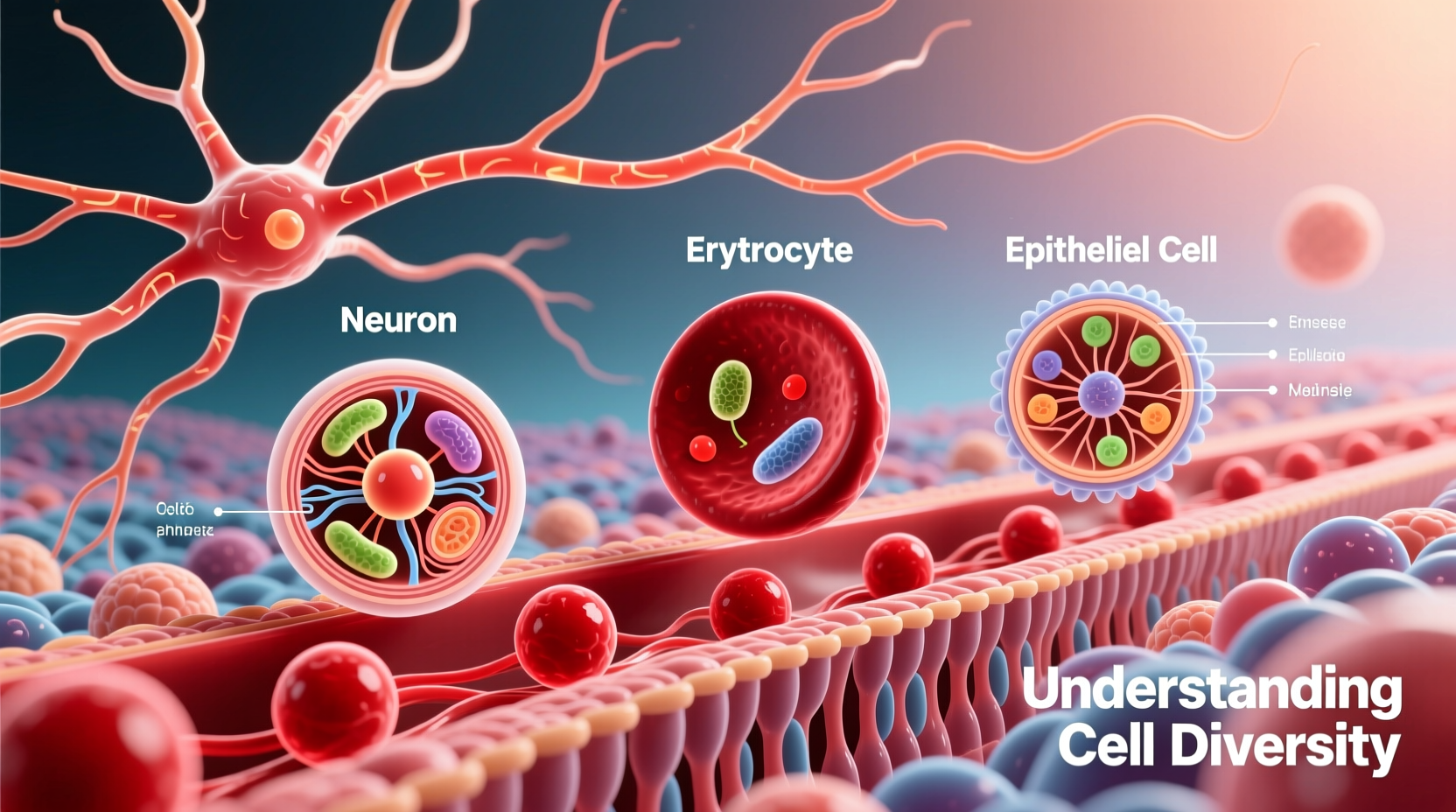

All human cells contain the same genetic blueprint—the full set of DNA—but only specific genes are activated in each cell type. This selective gene expression allows a neuron to transmit electrical signals, a red blood cell to carry oxygen, and a pancreatic beta cell to produce insulin, despite sharing identical DNA. This process, known as cellular differentiation, begins during embryonic development and continues throughout life through stem cell activity.

Differentiation transforms generic precursor cells into highly specialized units. For example, muscle cells develop contractile proteins like actin and myosin, while epithelial cells form tight junctions to create protective barriers. These structural and functional adaptations allow tissues and organs to perform distinct roles essential for survival.

Functional Efficiency Through Specialization

One of the primary reasons for cell diversity is efficiency. A single cell trying to perform every biological function would be overwhelmed. By dividing labor among specialized cells, organisms achieve greater metabolic efficiency, faster response times, and improved adaptability.

Consider the human nervous system. Neurons are optimized for rapid communication using electrical impulses and neurotransmitters. Their long axons and synaptic connections make signal transmission over distances possible. In contrast, glial cells support neurons by providing insulation (oligodendrocytes), nutrients, and immune surveillance. Without this division of labor, neural processing would be significantly slower and less reliable.

Likewise, immune cells exhibit remarkable diversity. Macrophages engulf pathogens, B cells produce antibodies, and T cells identify infected or cancerous cells. This functional partitioning allows the immune system to respond precisely and effectively to diverse threats.

Cell Types and Their Primary Functions

| Cell Type | Primary Function | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|

| Red Blood Cell (Erythrocyte) | Transport oxygen using hemoglobin | No nucleus; biconcave shape increases surface area |

| Neuron | Transmit electrical and chemical signals | Long axons, dendrites, synapses |

| Osteocyte | Maintain bone structure | Embedded in mineralized matrix; communicate via canaliculi |

| Sperm Cell | Fertilize egg cells | Flagellum for motility; high mitochondrial density |

| Guard Cells | Regulate gas exchange in plants | Change shape to open/close stomata |

Evolutionary Advantages of Cell Diversity

Cellular diversity is not just a feature of advanced life—it's a product of evolution. Early life consisted of unicellular organisms capable of independent survival. Over time, some cells began cooperating, forming colonies where certain individuals took on supportive roles. This cooperation laid the foundation for true multicellularity.

Organisms like *Volvox*, a green alga, demonstrate this transition. It consists of hundreds of cells, with most dedicated to photosynthesis while a few specialize in reproduction. This simple division of labor improves reproductive efficiency without compromising energy production.

In more complex animals, natural selection favored organisms that could allocate cellular functions efficiently. Those with better-specialized cells—such as efficient oxygen carriers or responsive nerve networks—had higher survival rates. Thus, cell diversity became a cornerstone of evolutionary success.

“We don’t have one type of cell because nature doesn’t reward generalists when specialists can do the job better.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Evolutionary Biologist, University of Edinburgh

A Closer Look: How Stem Cells Enable Diversity

At the beginning of life, a zygote—a single fertilized egg—holds the potential to become any cell type. Through successive divisions and signaling cues from its environment, this cell gives rise to increasingly committed progenitor cells. This journey from totipotency to terminal differentiation is guided by precise molecular signals, including transcription factors and epigenetic modifications.

Adult organisms retain pockets of stem cells—in bone marrow, skin, and intestinal lining—that continue producing new specialized cells throughout life. Hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow, for instance, generate all blood cell lineages: red cells, white cells, and platelets. This ongoing production ensures tissue renewal and repair.

The ability to direct stem cell differentiation has also opened doors in regenerative medicine. Scientists are exploring ways to grow replacement tissues for conditions like Parkinson’s disease or spinal cord injuries by mimicking natural developmental signals.

Step-by-Step: How a Stem Cell Becomes Specialized

- Signal Reception: The stem cell receives chemical signals (e.g., growth factors) from neighboring cells.

- Gene Activation: Specific transcription factors turn on target genes while silencing others.

- Morphological Changes: The cell begins to change shape and structure (e.g., developing cilia or elongating).

- Functional Maturation: It starts performing its designated role (e.g., secreting hormones or conducting impulses).

- Integration: The mature cell integrates into existing tissue and communicates with adjacent cells.

Real-World Example: The Human Skin Barrier

The skin provides a compelling case study in cell diversity. Its outermost layer, the epidermis, is composed almost entirely of keratinocytes. These cells begin life in the basal layer, actively dividing and metabolically vibrant. As they move upward, they undergo terminal differentiation: they stop dividing, fill with keratin, and eventually die, forming a tough, waterproof barrier.

This transformation is essential. Without it, the body would lose water rapidly and be vulnerable to pathogens. Other skin cells play supporting roles: melanocytes produce pigment to shield against UV radiation, Langerhans cells act as immune sentinels, and Merkel cells detect light touch. Together, these diverse cell types create a dynamic, multifunctional organ critical for survival.

Common Misconceptions About Cell Types

Many assume that more complex organisms have vastly more genes than simpler ones. However, humans have roughly 20,000 protein-coding genes—similar to a roundworm or fruit fly. The difference lies not in gene count but in how those genes are regulated and how cells diversify their functions.

Another misconception is that once a cell is specialized, it cannot change. While most cells remain fixed in their identity, research in cellular reprogramming shows that under certain conditions, adult cells can be reverted to a pluripotent state (induced pluripotent stem cells) or even directly converted into other cell types—a process called transdifferentiation.

FAQ

Why can't one cell type do everything?

A single cell attempting all functions would face trade-offs in efficiency, size, and energy use. Specialization allows optimization—like having a dedicated engine, sensor, and defense unit instead of one jack-of-all-trades component.

Are all cells in the body different?

There are approximately 200 distinct cell types in the human body, grouped into families (e.g., muscle, nerve, connective tissue). While individual cells within a type share core features, recent single-cell studies show subtle variations even among “identical” cells, suggesting deeper layers of diversity.

Do plants have different cell types too?

Yes. Plants have specialized cells such as xylem for water transport, phloem for nutrient distribution, and palisade mesophyll cells optimized for photosynthesis. Guard cells regulate gas exchange, and root hair cells increase absorption surface—all crucial for plant survival.

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity of Life

Cell diversity is not merely a biological curiosity—it is the foundation of complex life. From the oxygen-carrying red blood cell to the signal-firing neuron, each specialized unit contributes to a larger, coordinated system. This division of labor enhances efficiency, supports adaptation, and enables organisms to thrive in diverse environments.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?