When a basketball hits the floor and springs back into the air, it seems like simple magic. But beneath that bounce lies a complex interplay of physics principles—elasticity, energy conservation, air pressure, and material science. Understanding why basketballs bounce isn’t just fascinating; it enhances how players interact with the ball, influences equipment design, and reveals fundamental truths about motion and force.

The bounce is not guaranteed. Change the surface, temperature, or inflation level, and the rebound changes dramatically. To grasp what’s really happening when a ball drops and rises again, we need to examine the forces at work from the moment of impact to liftoff.

The Role of Elasticity in Bouncing

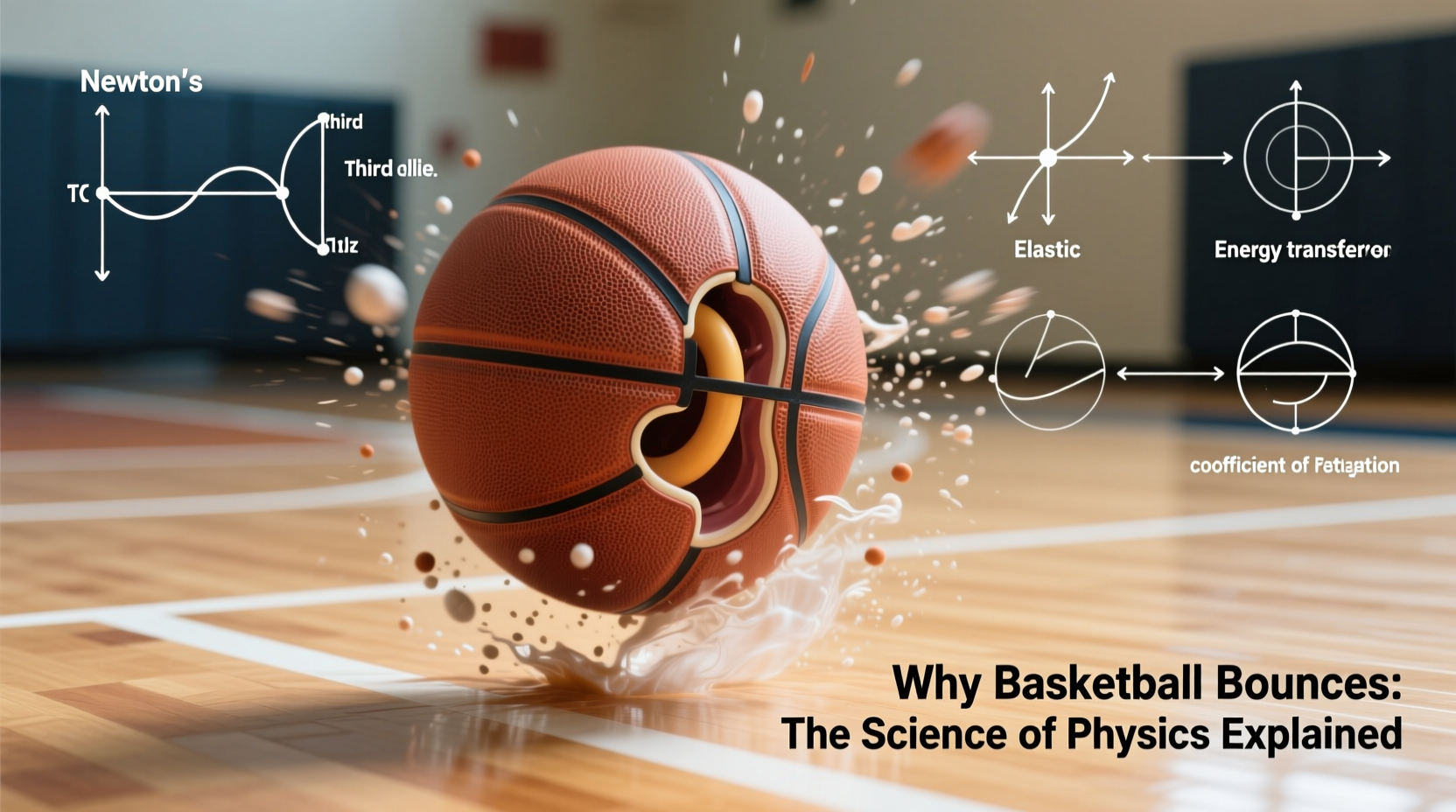

Elasticity refers to a material’s ability to return to its original shape after being deformed. Basketballs are made from synthetic rubber, composite leather, or genuine leather over an inflatable inner bladder—typically butyl rubber. These materials are chosen specifically for their elastic properties.

When a basketball strikes the ground, it compresses slightly. The outer shell and internal air pressure resist this deformation, storing potential energy. As the ball rebounds, that stored energy converts back into kinetic energy, propelling the ball upward. This rapid compression and recovery cycle is central to the bounce.

Not all materials behave this way. A lump of clay, for example, deforms permanently upon impact and doesn’t rebound. A steel ball bearing may be rigid, but it lacks sufficient elasticity to absorb and return energy efficiently on typical surfaces like hardwood or asphalt. The basketball sits in a sweet spot: soft enough to deform, elastic enough to recover.

Air Pressure and Internal Dynamics

The air inside a basketball plays a critical role in its bounce. Most regulation basketballs are inflated to between 7.5 and 8.5 psi (pounds per square inch). This pressurized air acts as a spring within a spring: while the rubber bladder provides structural elasticity, the compressed gas amplifies the restoring force during impact.

When the ball hits the floor, the bottom flattens, increasing internal pressure momentarily. The high-pressure air pushes outward against the compressed section, accelerating the ball’s return to spherical shape. This internal pressure wave contributes significantly to the speed and height of the rebound.

If a ball is underinflated, it deforms too much on impact, wasting energy through excessive surface contact and heat. Overinflation can make the ball too rigid, reducing dwell time on the surface and leading to erratic bounces. Both extremes diminish playability and responsiveness.

“Air pressure fine-tunes the dynamic response of the ball. It’s not just about firmness—it’s about timing the energy return.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Sports Biomechanics Researcher, University of Michigan

Energy Transfer and the Coefficient of Restitution

No bounce is 100% efficient. Some energy is always lost during impact due to heat, sound, and internal friction. The efficiency of a bounce is measured by the coefficient of restitution (COR), a ratio comparing the speed after impact to the speed before impact.

For a basketball dropped from a height onto a hard surface, the COR typically ranges between 0.75 and 0.85. That means the ball returns to 56% to 72% of its original drop height (since bounce height relates to the square of velocity).

The formula for COR is:

COR = √(bounce height / drop height)

For example, if a ball dropped from 1 meter rebounds to 0.75 meters:

COR = √(0.75 / 1) ≈ 0.87

This value helps manufacturers test performance and ensures consistency across game balls. Lower COR values indicate poor elasticity or incorrect inflation.

Factors That Reduce Energy Return

- Surface hardness: Softer surfaces (like carpet) absorb more energy than hardwood or concrete.

- Temperature: Cold reduces air pressure and stiffens rubber, lowering bounce.

- Wear and tear: Micro-cracks or moisture absorption degrade material resilience.

- Spin and angle: Oblique impacts dissipate energy laterally, reducing vertical rebound.

Real-World Example: The NBA Regulation Test

The National Basketball Association has strict standards for ball performance. One key test involves dropping a new ball from a height of 72 inches (1.83 meters) onto a solid maple wood surface. The ball must rebound to a height between 49 and 54 inches (1.24–1.37 meters).

In practice, this means quality control labs use high-speed cameras and laser sensors to measure exact rebound trajectories. If a batch fails, engineers investigate whether the issue stems from bladder thickness, rubber formulation, or stitching tension. Even minor deviations affect player feel and game dynamics.

During the 2017 preseason, several teams reported inconsistent ball behavior after switching suppliers. Independent testing revealed a 5% lower COR than standard, prompting immediate recalibration of manufacturing processes. This incident underscores how sensitive performance is to precise physical parameters.

Step-by-Step: How a Basketball Bounces (Micro-Timeline)

The entire bounce event lasts less than 0.01 seconds, but it unfolds in distinct phases:

- Contact (0 ms): The ball touches the surface at terminal velocity.

- Compression (0–4 ms): The bottom deforms, kinetic energy converts to elastic and thermal energy.

- Peak deformation (4–6 ms): Maximum flattening occurs; internal pressure peaks.

- Restoration (6–9 ms): Stored energy drives the ball back toward its round shape.

- Liftoff (9–10 ms): The ball loses contact with the surface, now moving upward.

This sequence repeats with each dribble, though successive bounces lose height due to cumulative energy loss.

Do’s and Don’ts for Maintaining Optimal Bounce

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Check inflation monthly using a pressure gauge | Use car tire gauges—they’re inaccurate for low psi ranges |

| Store indoors at room temperature | Leave the ball in a hot car or freezing garage |

| Wipe down with a damp cloth after outdoor play | Submerge in water or use harsh cleaners |

| Rotate multiple balls to extend lifespan | Dribble aggressively on rough asphalt long-term |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t a deflated basketball bounce?

A deflated ball lacks sufficient internal air pressure to generate a restoring force. When it hits the ground, the walls collapse inward and absorb most of the energy through prolonged deformation rather than snapping back. This results in minimal rebound or none at all.

Can temperature affect a basketball’s bounce?

Yes. Cold temperatures reduce air pressure inside the ball and stiffen the rubber, decreasing elasticity. A ball left outside in winter may bounce less than half as high as it does at room temperature. Conversely, overheating can weaken adhesives and risk bursting.

Why do some basketballs feel “livelier” than others?

Beyond inflation, factors like bladder quality, panel construction, and micro-texture of the cover influence tactile feedback. Higher-end balls use multi-layered bladders and tacky composites that enhance energy return and grip, creating a more responsive feel during dribbling and shooting.

Actionable Checklist: Maximizing Your Ball’s Bounce Life

- ✅ Inflate to manufacturer-recommended PSI (usually 7.5–8.5)

- ✅ Use a proper hand pump with a built-in gauge

- ✅ Play primarily on smooth, hard surfaces when possible

- ✅ Avoid extreme temperatures during storage and transport

- ✅ Inspect seams and valves monthly for leaks or wear

- ✅ Clean with mild soap and water—never machine wash

- ✅ Replace after visible cracking, persistent flat spots, or poor rebound

Conclusion: Master the Science, Improve the Game

The bounce of a basketball is far more than a simple rebound—it’s a miniature physics demonstration occurring thousands of times in every game. From Newton’s laws to thermodynamics, the principles governing motion, pressure, and material behavior all converge in that split-second impact.

Players who understand these dynamics gain an edge. They recognize when a ball isn’t performing optimally, know how to maintain it, and appreciate the engineering behind consistent play. Coaches and parents can teach young athletes not just *how* to dribble, but *why* the ball responds the way it does—turning casual play into a lesson in real-world science.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?