Fingerprints are one of the most distinctive biological traits shared by all humans. From birth to death, these intricate ridge patterns remain unchanged, forming a unique signature on each fingertip. While their use in forensic science is well known, the deeper question remains: why did such complex patterns evolve in the first place? The answer lies at the intersection of biology, physics, and evolutionary adaptation. Far from being mere quirks of human anatomy, fingerprints serve essential roles in enhancing tactile sensitivity, improving grip, and even contributing to our interaction with the environment. This article explores the evolutionary origins, biomechanical functions, and scientific insights behind why humans—and only a few other primates—develop these remarkable skin patterns.

The Evolutionary Origins of Fingerprints

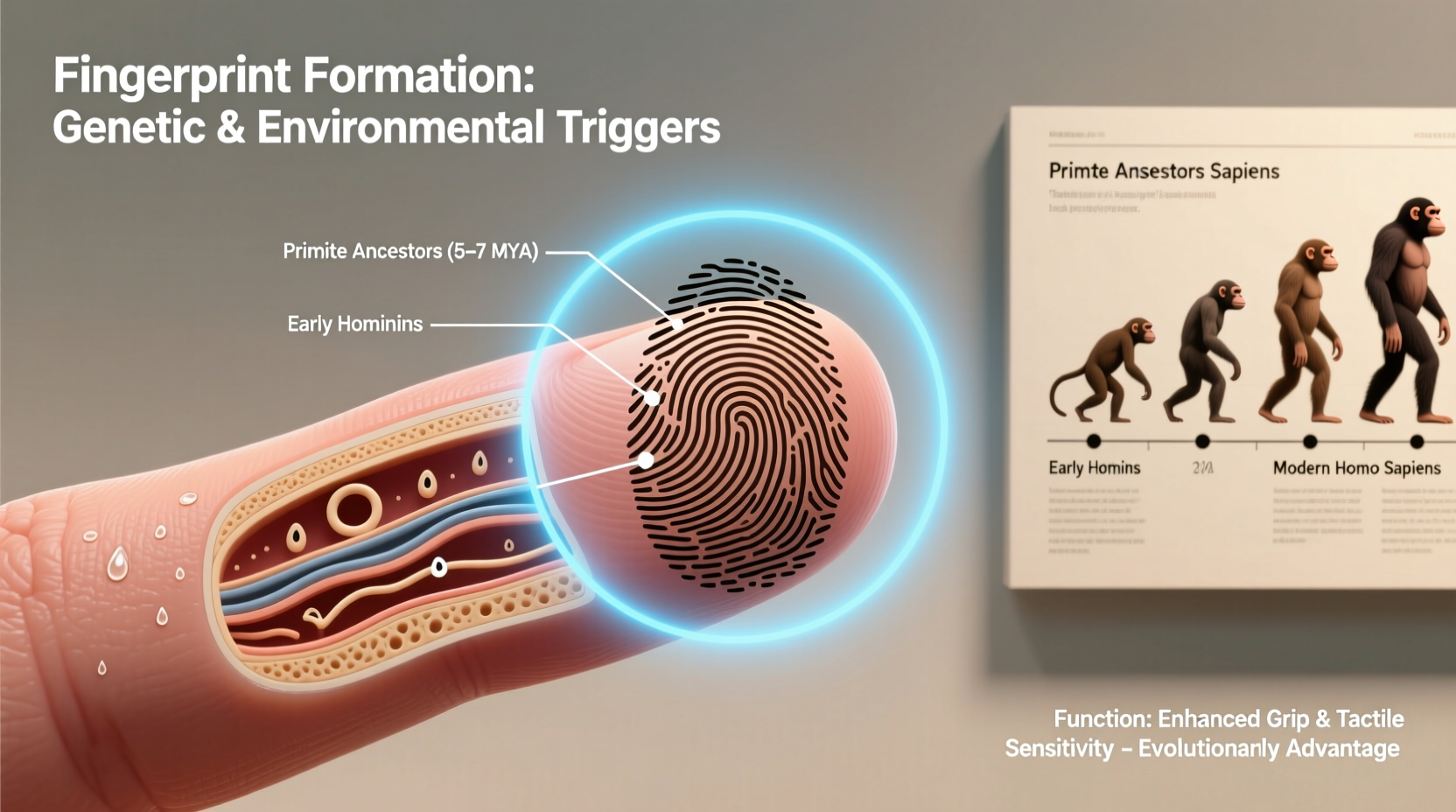

Fingerprints, or dermatoglyphs, begin forming during fetal development around the 10th to 15th week of gestation. Their formation is influenced by genetic factors and environmental conditions in the womb, resulting in patterns that are both heritable and uniquely individual. But long before forensic databases or biometric scanners, fingerprints had already been shaped by millions of years of natural selection.

Evolutionary biologists believe that friction ridges evolved primarily in arboreal primates as an adaptation for climbing and manipulating objects in complex environments. Early primates relied heavily on precise hand movements to grasp branches, handle food, and navigate dense forest canopies. In such settings, enhanced grip and tactile feedback would have conferred significant survival advantages.

Studies comparing primate species show that those with more developed fingerprints—such as chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans—also exhibit advanced manual dexterity. These animals use their hands not just for locomotion but also for tool use and social grooming, suggesting that fine motor control was a key driver in the evolution of ridge patterns.

“Fingerprints aren’t random—they’re the result of selective pressures favoring better grip and sensory resolution in tree-dwelling ancestors.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Evolutionary Biologist, University of Edinburgh

How Fingerprints Improve Grip and Friction

A common misconception is that fingerprints increase friction by acting like tire treads. However, recent research challenges this idea. In dry conditions, smooth fingertips actually generate more friction than ridged ones due to greater surface contact. So what’s the real mechanical advantage?

The truth emerges when moisture enters the equation. Human fingertips naturally secrete small amounts of sweat, which can reduce grip on smooth surfaces. Fingerprints channel this moisture away through tiny grooves between the ridges, maintaining optimal skin hydration levels. This microfluidic system prevents slippage by creating a balance between wetness and dryness—similar to how rain treads on tires displace water to maintain road contact.

Additionally, fingerprints enhance grip on rough or uneven surfaces by increasing compliance—the ability of soft tissues to conform to microscopic textures. The ridges deform slightly under pressure, allowing them to “lock” into surface irregularities. This effect improves handling precision, especially when dealing with fragile or delicate objects.

The Role of Fingerprints in Tactile Sensation

Beyond mechanics, fingerprints play a crucial role in how we perceive the world through touch. Embedded within the skin are specialized nerve endings called mechanoreceptors, particularly Merkel cells and Meissner’s corpuscles, which respond to pressure, vibration, and texture changes.

Fingerprints amplify subtle vibrations generated when fingers move across a surface—a phenomenon known as \"stick-slip\" motion. As the ridges catch and release microscopic bumps, they produce rhythmic signals that are picked up by underlying nerves. These signals are then transmitted to the brain, where they are interpreted as detailed textural information.

In essence, fingerprints act as biological signal enhancers. They filter and modulate tactile input, making it easier for the nervous system to detect edges, patterns, and material differences. This heightened sensitivity would have been vital for early humans identifying edible plants, crafting tools, or sensing danger through touch alone.

Neurological studies using fMRI scans confirm that fingerprinted areas of the hand activate larger regions of the somatosensory cortex compared to non-ridged skin, underscoring their importance in neural processing of touch.

Uniqueness and Biometric Applications

While the functional benefits of fingerprints are rooted in evolution, their uniqueness has led to widespread modern applications in identification and security. No two individuals—even identical twins—have the same fingerprint patterns. This individuality arises from minor variations in prenatal development, including blood flow, hormone levels, and finger positioning in the amniotic sac.

Forensic science has leveraged this trait since the late 19th century, beginning with Sir Francis Galton’s classification system and culminating in today’s digital biometric systems. Modern smartphones, border controls, and criminal investigations rely on fingerprint recognition due to its reliability and ease of collection.

However, while useful, biometric reliance raises ethical concerns about privacy and data misuse. Unlike passwords, fingerprints cannot be changed if compromised, making secure storage critical.

| Feature | Biological Purpose | Modern Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ridge Patterns | Enhance grip and moisture management | Individual identification |

| Tactile Amplification | Improve texture discrimination | Haptic technology design |

| Developmental Uniqueness | Byproduct of embryonic variation | Forensics and access control |

| Stability Over Time | Consistent skin structure post-birth | Long-term identity verification |

Common Misconceptions About Fingerprints

Despite decades of study, several myths persist about how fingerprints work. Addressing these misconceptions helps clarify their true biological significance.

- Myth: Fingerprints increase friction on all surfaces.

Reality: They reduce friction on smooth, dry surfaces but improve grip in moist conditions by managing sweat. - Myth: Ridge patterns are designed for identification.

Reality: Identification is a modern application; evolution favored functionality over identifiability. - Myth: Cutting off fingertips erases fingerprints permanently.

Reality: Unless deep tissue damage occurs, fingerprints regenerate after healing.

Mini Case Study: A Climber’s Hands

Consider Maya, an experienced rock climber who spends hours scaling indoor walls and natural cliffs. During training, she noticed that her grip faltered significantly when her hands were either too dry or overly sweaty. Using chalk helped absorb excess moisture, but she found that her natural fingerprint ridges played a key role in maintaining control.

On textured rock faces, the ridges allowed her fingertips to conform to minute crevices, enhancing tactile feedback and stability. When gripping polished holds, however, moisture buildup became problematic—until she began regulating hand sweat with anti-perspirant wipes before sessions. This real-world example illustrates how fingerprints function optimally within a narrow physiological window, supporting both grip and sensory input depending on environmental conditions.

Scientific Research and Future Insights

Recent advances in materials science and robotics are drawing inspiration from human fingerprints. Engineers developing artificial skin for prosthetics and humanoid robots are replicating ridge-like structures to improve robotic grip and object recognition.

One notable project at Stanford University created a synthetic fingertip covered in micro-ridges mimicking human dermatoglyphs. Tests showed a 30% improvement in handling wet objects compared to smooth-surfaced sensors. Such innovations highlight how understanding biological design can lead to breakthroughs in technology.

Meanwhile, geneticists are exploring the link between fingerprint patterns and broader developmental markers. Certain congenital conditions, such as Down syndrome and Adermatoglyphia (a rare disorder causing absence of fingerprints), are associated with specific gene mutations like SMARCAD1. Studying these links may one day allow early diagnosis of developmental disorders through dermatoglyphic analysis.

Checklist: Understanding and Caring for Your Fingerprint Functionality

- Maintain balanced hand moisture—use moisturizer for dryness, chalk or wipes for excessive sweating.

- Avoid harsh chemicals that strip natural oils and damage ridge integrity.

- Protect hands during repetitive tasks (e.g., weightlifting, typing) to prevent ridge wear.

- Monitor changes in skin texture—if ridges flatten or crack persistently, consult a dermatologist.

- Be mindful of biometric data security—limit unnecessary fingerprint enrollment on devices.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can fingerprints change over time?

No, the fundamental pattern of ridges remains constant throughout life. However, temporary changes can occur due to injury, aging, or skin conditions. Deep cuts may alter the appearance, but once healed, the original pattern typically regenerates unless scar tissue disrupts the dermal layer.

Do animals have fingerprints?

True fingerprints are rare in nature. Besides humans, some primates (like chimpanzees and gorillas) and koalas have similar ridge patterns. Koalas, despite being marsupials, evolved analogous friction ridges independently—likely due to their need for strong grip while climbing eucalyptus trees.

Is it possible to be born without fingerprints?

Yes, though extremely rare. A condition called adermatoglyphia results in completely smooth fingertips. Individuals with this genetic mutation face practical difficulties, such as trouble with biometric scanners and increased slipperiness when handling objects. It is linked to mutations in the SMARCAD1 gene.

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity of a Tiny Trait

Fingerprints are far more than forensic tools or biometric keys—they are elegant solutions forged by evolution to solve real-world problems of grip, sensation, and environmental interaction. Their persistence across lifetimes and universality among humans speak to their biological importance. From aiding our primate ancestors in the treetops to enabling modern touchscreen navigation, fingerprints quietly support countless daily actions.

Understanding their dual role in physical function and personal identity enriches our appreciation of human biology. As science continues to decode their mysteries—from genetic origins to technological mimicry—we gain not only insight into ourselves but also inspiration for future innovation.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?