Blown fuses in Christmas light strings are more than a seasonal nuisance—they’re a warning sign. Every time a fuse pops, it interrupts your festive rhythm, delays your decorating plans, and, more importantly, hints at underlying electrical stress that could compromise safety. Unlike household circuit breakers that trip to protect wiring, miniature fuses in light sets (typically 3- to 5-amp glass or ceramic fuses) exist solely to guard against overcurrent in low-voltage, high-density string circuits. When they fail repeatedly, it’s rarely random—it’s physics, wear, and sometimes poor design converging. This article cuts through holiday myths and focuses on what actually causes repeated fuse failures: not “bad luck,” but measurable, fixable conditions like voltage mismatch, moisture ingress, aging insulation, and daisy-chaining errors. We’ll walk through diagnostic steps, real-world examples, and preventive actions grounded in National Electrical Code (NEC) guidelines and UL 588 safety standards—so you can enjoy brilliant, reliable lighting without risking outlets, extension cords, or peace of mind.

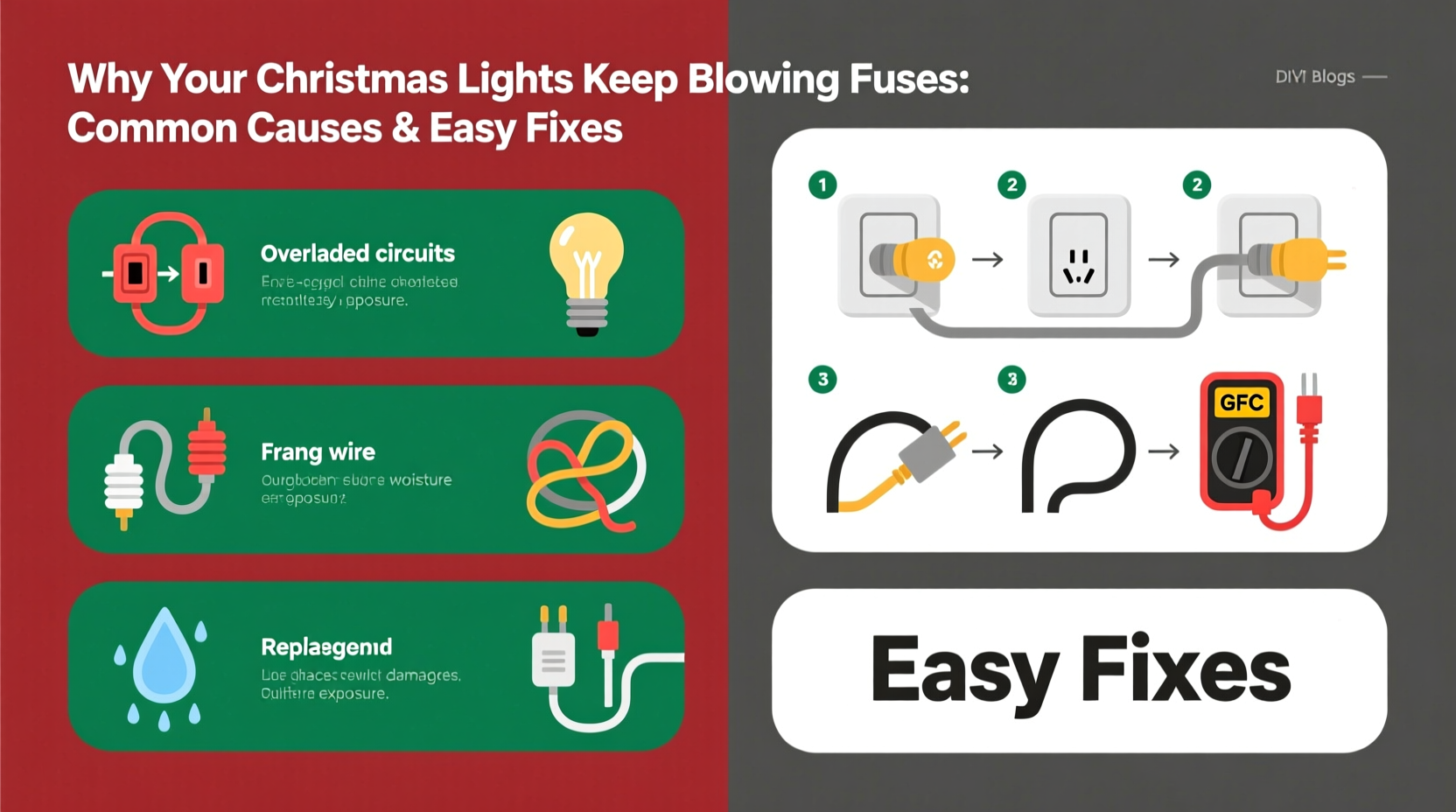

1. Overloading the Circuit: The #1 Culprit

Most residential outdoor outlets are fed by 15- or 20-amp circuits—yet many homeowners unknowingly exceed safe limits when connecting multiple light strings. A single 100-light incandescent string draws about 0.3–0.5 amps; LED versions draw just 0.04–0.12 amps. But here’s where confusion sets in: manufacturers’ “maximum connectable” labels refer only to the *light string’s internal wiring*, not your home’s branch circuit capacity. For example, a label saying “Connect up to 210 strings” assumes ideal lab conditions—no voltage drop, no aging wires, no shared outlets. In reality, plugging 12 LED strings (each drawing ~0.1 A) into one outlet may seem safe (1.2 A total), but add a 1,500-watt space heater on the same circuit—or even a refrigerator cycling on—and you’ve crossed into overload territory. Voltage sags under load cause current spikes across the entire string, tripping fuses prematurely.

2. Moisture, Corrosion, and Poor Connections

Outdoor lighting lives in a harsh environment—rain, dew, freeze-thaw cycles, and salt air accelerate degradation. Even lights rated “weather-resistant” aren’t waterproof. Moisture seeps into cracked insulation, corroded bulb sockets, or poorly sealed plug housings, creating micro-shorts. These don’t always cause immediate failure; instead, they generate intermittent arcing—tiny sparks inside the socket—that erodes metal contacts and heats the fuse element over time. You might notice flickering before the fuse blows, or bulbs that dim unpredictably near damp sections of the string. Corrosion is especially aggressive on older copper-clad aluminum (CCA) wire, common in budget strings from 2010–2018. Once oxidation forms, resistance rises locally, causing heat buildup that stresses the fuse far beyond its rated tolerance.

| Symptom | Most Likely Cause | Immediate Action |

|---|---|---|

| Fuse blows only after rain or morning dew | Moisture ingress at plug or socket | Unplug, dry thoroughly with compressed air, inspect for cracks, replace plug if housing is brittle |

| Greenish-white crust around bulb bases | Copper corrosion or aluminum oxide buildup | Remove affected bulbs, gently clean socket contacts with electrical contact cleaner and soft brush, replace corroded bulbs |

| Fuse blows instantly on power-up | Short circuit from damaged wire or pinched insulation | Trace wire for kinks, abrasions, or chew marks; cut out damaged section and splice with waterproof wire nuts |

3. Daisy-Chaining Errors and Compatibility Conflicts

Daisy-chaining—plugging one string into another—is convenient but perilous when done incorrectly. Not all light strings are designed to be connected end-to-end. Incandescent and LED strings use different internal resistors, rectifiers, and current regulation. Mixing them—even if both are labeled “LED”—can create backfeed paths or unbalanced loads. Worse, many modern LED strings include built-in surge suppression and constant-current drivers. Connecting incompatible models forces one driver to compensate for another’s instability, resulting in current surges that overwhelm the fuse. UL 588 mandates that only strings bearing the exact same manufacturer, model number, and “Connectable” certification mark should be chained. Yet retail packaging rarely clarifies this, leading consumers to assume “all LEDs are compatible.”

“Daisy-chaining non-identical LED strings is like mixing transmission fluids—it might run for a while, but eventual failure is guaranteed. Fuses blow because the system is fighting itself.” — Carlos Mendez, Senior Electrical Safety Engineer, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

4. Aging Components and Thermal Fatigue

Christmas lights age faster than most realize. Indoor storage doesn’t stop chemical degradation. PVC insulation becomes brittle after 3–5 years due to UV exposure (even residual indoor light), plasticizer migration, and thermal cycling. Each time you plug in a string, the fuse element heats and cools—expanding and contracting minutely. Over dozens of seasonal cycles, microscopic cracks form in the fuse’s internal wire or solder joints. These cracks increase resistance, generating localized heat that eventually exceeds the fuse’s melting point. Bulbs themselves contribute: as tungsten filaments thin with use, cold resistance drops, causing higher inrush current at startup—up to 10× the steady-state draw. That initial surge is what trips marginal fuses. Older LED strings suffer from capacitor aging in their drivers; dried-out electrolytic capacitors lose capacitance, destabilizing current flow and stressing fuses.

Mini Case Study: The Porch Light Pattern

In December 2022, Sarah K., a homeowner in Portland, OR, reported her front-porch lights blowing fuses every 3–4 days. She used 8 identical 200-bulb LED strings (rated 0.07 A each), plugged into two GFCI outlets via heavy-duty 12-gauge extension cords. Diagnostics revealed no overloading—the total draw was just 0.56 A per outlet. What she hadn’t noticed was that the first string in each chain ran directly along a cedar planter box, where nightly condensation pooled beneath the cord. Using a multimeter, an electrician found 0.8 mA leakage current between the string’s neutral and ground—well below GFCI trip threshold (5 mA), but enough to gradually oxidize the fuse holder’s brass contacts. After replacing the first string’s plug with a marine-grade waterproof connector and elevating the cord off the planter, the fuses lasted the full season. Her takeaway? “It wasn’t the number of lights—it was where the first one lived.”

5. Faulty Fuses, Fuse Holders, and Hidden Damage

Not all fuses are created equal. Cheap replacement fuses often lack precise calibration—some test 10–15% below their labeled rating. A “3A” fuse that actually fails at 2.6A will blow unnecessarily under normal load. Equally problematic are degraded fuse holders: spring tension weakens over time, increasing contact resistance and heat. You might hear faint buzzing or smell ozone near the fuse compartment—a sign of arcing. Physical damage is also common: stepping on a string, closing a door on a cord, or storing lights tightly wound creates invisible nicks in insulation. These defects rarely show until voltage is applied, then manifest as intermittent shorts. Always inspect the entire string—not just bulbs—before installation: look for flattened sections, discoloration on wire jackets, or stiffness in cord flexibility.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic & Fix Protocol

- Unplug everything. Never work on live circuits—even low-voltage strings can carry hazardous voltage during surge events.

- Inspect visually. Examine every inch of cord, plug, and socket for cracks, fraying, melted plastic, or corrosion. Discard any string with compromised insulation.

- Test continuity. With a multimeter set to continuity mode, check each bulb socket (remove bulb first). A reading of “OL” (open loop) means broken filament or internal short—replace bulb. If socket reads continuity with bulb removed, the socket is shorted—replace entire section.

- Check fuse rating. Match replacement fuses exactly to the original specs printed on the fuse holder or packaging (e.g., “3AG 3A 125V”). Never substitute with automotive or generic fuses.

- Isolate and test. Plug in only one string at a time. If it blows immediately, the fault is internal. If it works alone but fails when chained, compatibility or overload is confirmed.

- Verify grounding and GFCI function. Press TEST and RESET on outdoor GFCIs monthly. A failing GFCI can induce false trips mistaken for fuse issues.

FAQ

Can I replace a blown fuse with a higher-amp one for longer life?

No—this is dangerous and violates UL safety certification. A 5A fuse in a circuit designed for 3A allows excessive current to flow, overheating wires and potentially igniting insulation. Fuses are precision safety devices, not convenience items. If fuses blow repeatedly, the root cause must be fixed—not bypassed.

Why do only the first few bulbs in my string go dark when the fuse blows?

Most mini-light strings use series wiring: current flows through each bulb sequentially. A single open filament breaks the circuit, cutting power to all downstream bulbs. The fuse blows to prevent sustained current through a partial short—often caused by a bulb’s internal shunt failing to activate properly. Modern “shunt-wire” bulbs are designed to bypass a dead filament, but humidity or corrosion can disable this feature.

Do LED lights really eliminate fuse problems?

They reduce risk significantly—but don’t eliminate it. While LEDs draw less power and generate less heat, their electronic drivers introduce new failure modes: voltage spikes from nearby lightning, capacitor failure, or incompatibility with dimmers and timers. A 2023 NFPA analysis found 22% of reported LED light fire incidents involved driver-related faults—not bulb failure.

Conclusion

Your Christmas lights shouldn’t feel like a gamble. Repeated fuse failures aren’t part of the holiday tradition—they’re preventable signals pointing to specific, addressable issues: overloaded circuits, moisture intrusion, incompatible chaining, aging components, or physical damage. By applying these diagnostics—not guesswork—you gain control over reliability and safety. Start this season by auditing your setup: measure actual outlet load, inspect every connection, verify fuse specifications, and retire strings older than five years. Small habits compound: storing lights loosely on reels (not tangled), using weatherproof connectors outdoors, and testing GFCIs monthly extend lifespan and reduce risk. The joy of twinkling lights shouldn’t come with anxiety or burnt smells. It should come with confidence—knowing your display shines brightly, safely, and consistently, year after year.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?