Walk into a used bookstore, an antique library, or even your attic, and you might catch a familiar scent—sweet, warm, slightly woody, with a hint of vanilla. It’s not from candles or air fresheners. That distinctive aroma comes from the books themselves. But why do old books smell like vanilla? The answer lies in chemistry, time, and the natural breakdown of materials used in bookmaking centuries ago. This article explores the science behind this beloved fragrance, breaking down how paper degrades, what compounds are released, and why certain books carry this nostalgic scent more than others.

The Chemistry Behind the Scent

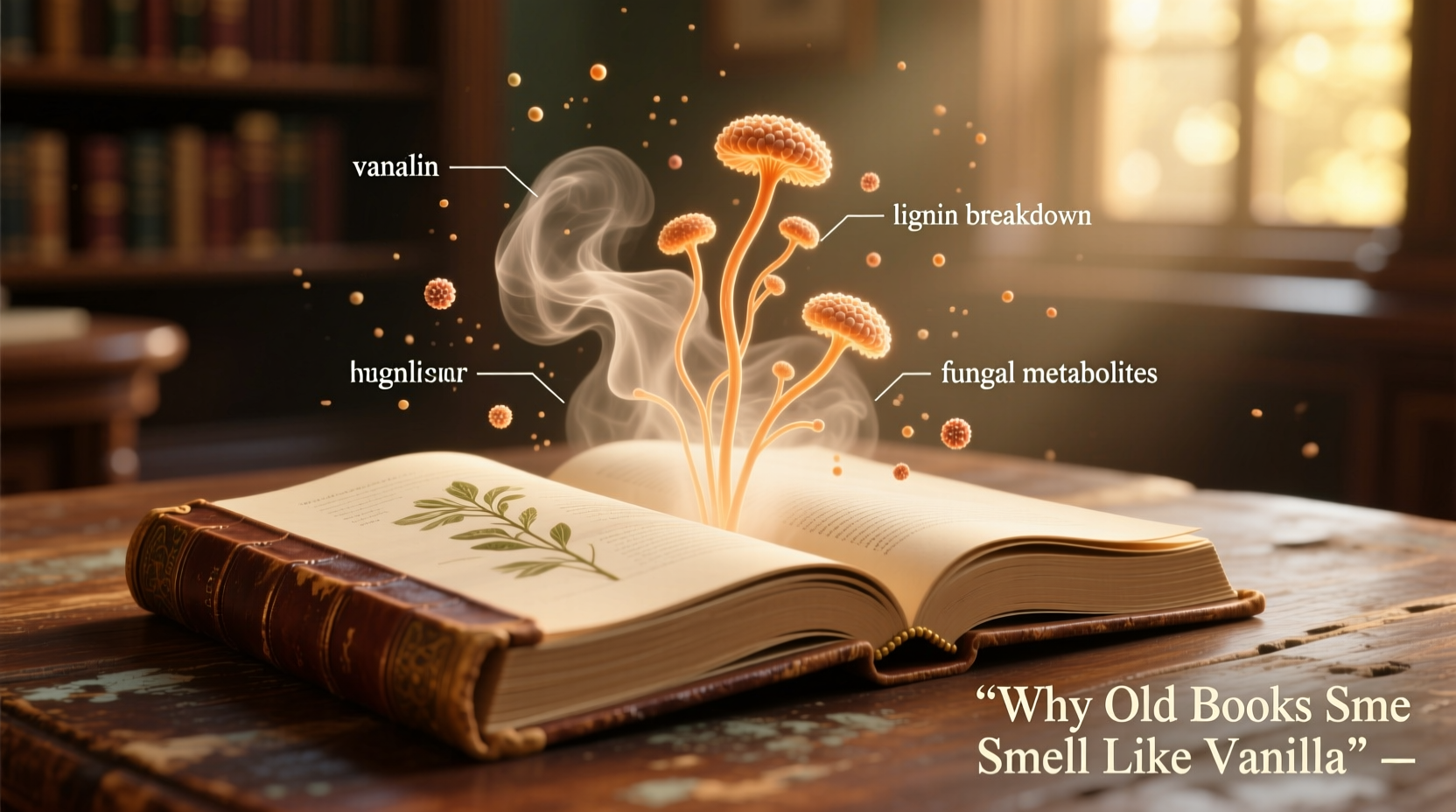

The vanilla-like odor associated with old books is primarily due to the chemical breakdown of lignin, a complex organic polymer found in wood. Most paper before the 20th century was made from wood pulp that contained high levels of lignin. Unlike modern paper, which undergoes processing to remove much of this compound, older paper retained it—setting the stage for slow chemical transformation over decades.

As lignin breaks down through oxidation and hydrolysis (reactions with oxygen and moisture), it releases aromatic molecules. One of the most notable byproducts is **vanillin**—the same compound responsible for the flavor and scent of vanilla beans. While vanillin is synthetically produced today for commercial use, its presence in decaying paper is entirely natural and unintentional.

Other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) also contribute to the overall bouquet. These include:

- Benzaldehyde – gives an almond-like note

- Furfural – adds a sweet, bready aroma

- Hydroxyacetone – contributes caramelized sugar tones

- Ethyl benzoate – imparts fruity nuances

Together, these form a layered olfactory profile often described as warm, musty-sweet, or nostalgically comforting. The dominance of vanillin, however, makes “vanilla” the most recognizable descriptor.

Why Not All Old Books Smell Like Vanilla

You may have noticed that some old books have a strong vanilla scent while others smell musty, moldy, or nearly odorless. Several factors influence whether a book develops that signature aroma:

- Paper Composition: Books printed before the late 1800s often used rag paper (made from cotton or linen), which contains little to no lignin. These books tend to age without developing a vanilla scent but may still emit subtle earthy notes.

- Ink Type: Iron gall ink, commonly used in manuscripts, reacts differently with paper and can suppress certain VOC emissions.

- Storage Conditions: Temperature, humidity, light exposure, and airflow all affect the rate and pathway of chemical degradation. Cool, dry environments slow decay; damp, warm spaces promote mold instead of vanillin production.

- Age of the Book: The vanilla scent tends to peak between 50 and 150 years after printing. Older books may have already off-gassed most volatile compounds, leaving behind only faint traces.

Books printed during the mass-production era of the 19th and early 20th centuries—when wood-pulp paper became standard—are the most likely candidates for that vanilla-rich aroma.

How Lignin Breakdown Works Over Time

Lignin serves as nature's \"glue,\" binding cellulose fibers in plant cell walls. In trees, it provides rigidity. When processed into paper, especially without full delignification, it remains embedded in the sheet. Over time, environmental exposure triggers gradual molecular changes:

| Stage | Process | Resulting Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| 0–20 years | Initial oxidation begins at surface fibers | Trace aldehydes, minimal scent |

| 20–70 years | Hydrolysis accelerates; lignin fragments break down | Vanillin, furfural, benzaldehyde become detectable |

| 70–120 years | Peak VOC emission; optimal balance of breakdown and retention | Strongest vanilla-like aroma |

| 120+ years | Most volatiles have dissipated; paper yellows further | Scent fades; remaining odors lean toward dust or mildew |

This timeline explains why mid-century novels, school textbooks from the 1940s, or encyclopedias from the early 1900s often deliver the richest sensory experience. After a century, the paper has aged enough to produce vanillin, but not so long that the compounds have fully evaporated.

“Old books are like chemical time capsules. Each page holds a record of its material origins and environmental history—encoded in scent.” — Dr. Elena Torres, Preservation Chemist, University of Edinburgh

Preserving the Scent: Practical Tips for Collectors

If you own vintage books and appreciate their unique fragrance, you might want to preserve both the physical integrity and the olfactory character. While you can’t stop aging entirely, you can slow it meaningfully.

Step-by-Step Guide to Long-Term Book Care

- Control Humidity: Maintain relative humidity between 45% and 55%. Too dry causes brittleness; too moist encourages mold.

- Avoid Direct Sunlight: UV radiation breaks down cellulose and speeds up lignin oxidation, leading to rapid fading and embrittlement.

- Use Acid-Free Materials: Store books in acid-free boxes or wrap them in archival tissue paper to prevent acid migration.

- Ensure Air Circulation: Keep shelves away from walls and allow space between books to reduce moisture buildup.

- Handle with Clean Hands: Oils and dirt from skin can stain pages and catalyze localized degradation.

While some collectors attempt to \"refresh\" the vanilla scent using essential oils or sprays, this practice is strongly discouraged by conservators. Artificial scents mask natural VOCs, compromise authenticity, and may introduce residues that damage paper over time.

Real-World Example: The Case of the 1898 Encyclopedia Set

In 2017, a private collector in Massachusetts acquired a complete set of *Chambers’s Encyclopaedia* from 1898 at a local estate sale. Stored in a cedar-lined cabinet in a bedroom closet, the volumes had been untouched for over 60 years. Upon opening the first volume, the buyer noted a pronounced vanilla-almond aroma, particularly strong along the spine and edges.

A preservation assessment revealed that the paper was standard groundwood pulp typical of late-Victorian publishing, with high lignin content. The cedar cabinet had provided stable temperature and moderate airflow, while the natural antimicrobial properties of cedar helped deter mold. However, the lack of light exposure meant slower degradation—delaying the peak scent phase until decades later.

Conservators advised gentle cleaning, relocation to a ventilated bookshelf away from exterior walls, and regular monitoring for insect activity. Within two years, the scent remained strong, confirming that proper storage could extend the life—and aroma—of historical paper materials well beyond expected timelines.

Do’s and Don’ts of Vintage Book Storage

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Store books upright with support | Lay books flat in stacks long-term |

| Use bookends to prevent slanting | Overcrowd shelves, causing spine strain |

| Dust regularly with soft brush | Use feather dusters that can scratch covers |

| Keep in rooms with consistent climate | Store near radiators, windows, or kitchens |

| Wrap rare books in breathable fabric | Seal books in plastic bags (traps moisture) |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the vanilla smell harmful?

No, the volatile compounds released by aging paper are present in extremely low concentrations and pose no health risk under normal conditions. However, individuals with chemical sensitivities may find prolonged exposure in poorly ventilated spaces uncomfortable.

Can new books be made to smell like old ones?

Some artisan publishers and perfumers have experimented with adding trace amounts of vanillin to paper or bindings to mimic the vintage scent. However, true connoisseurs argue that artificial replication lacks the complexity of naturally aged books. Additionally, introducing chemicals may compromise longevity.

Why do some old books smell bad instead of sweet?

Foul odors usually indicate mold, water damage, or bacterial growth. A sour, musty, or ammonia-like smell suggests active deterioration and possible infestation. These books should be isolated, inspected, and professionally treated if valuable.

Conclusion: Embracing the Science of Nostalgia

The vanilla scent of old books is more than just a pleasant quirk—it’s a testament to the quiet, ongoing chemistry of everyday materials. What we perceive as nostalgia is, in fact, a symphony of molecular decay, shaped by papermaking practices, environmental conditions, and the passage of time. Understanding this process deepens our appreciation for physical books, not just as vessels of knowledge, but as dynamic artifacts with sensory stories to tell.

Whether you’re a collector, a librarian, or simply someone who loves the smell of a secondhand bookstore, recognizing the science behind the scent empowers you to preserve these treasures wisely. Handle them with care, store them thoughtfully, and let them breathe—because every whiff of vanillin is a fleeting message from the past, slowly fading with each passing year.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?