It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you plug in your string of Christmas lights, and only the first 24 bulbs glow—while the rest sit stubbornly dark. Or perhaps the bottom half flickers weakly while the top remains bright. You check the fuse, swap bulbs, wiggle connections—and still, the problem persists. This isn’t random bad luck. It’s physics, circuit design, and decades of standardized (but fragile) wiring practices working against you. Understanding *why* half a string fails—and what’s really happening inside that plastic-coated wire—turns troubleshooting from guesswork into precision repair. This article breaks down the five most common wiring-related causes, explains how traditional incandescent and modern LED strings differ fundamentally in failure behavior, and gives you actionable diagnostics you can perform with nothing more than a multimeter and patience.

The Series Circuit Trap: Why One Break Kills Half the String

Most traditional incandescent mini-light strings—especially those manufactured before 2015—are wired in a series-parallel hybrid configuration. A typical 100-light string is divided into two or more independent 50-light series circuits. Each circuit runs end-to-end: current flows from the plug, through bulb #1, then #2, all the way to #50, and back to the neutral line. If *any single bulb* in that 50-bulb chain burns out, goes loose, or develops an open filament, the entire circuit stops conducting electricity. That’s why “half” the string dies—not because of a midpoint break, but because the manufacturer split the load across two separate series legs.

This design wasn’t arbitrary. It kept voltage per bulb low (typically 2.5V for 100-light sets on 120V systems), reduced heat, and allowed manufacturers to use thinner, cheaper wire. But it introduced a critical vulnerability: no redundancy. Unlike household wiring—where outlets operate in parallel and one dead socket doesn’t affect others—Christmas light circuits assume every component remains intact.

Shunt Failure: The Silent Saboteur in Incandescent Bulbs

Manufacturers added a clever workaround: the shunt. Inside each incandescent mini-bulb base is a tiny coiled wire (the shunt) coated in insulating material. When the filament is intact, current flows normally through it. But when the filament burns out, heat builds until the insulation melts—allowing the shunt to short-circuit across the broken filament, restoring continuity to the rest of the string.

Here’s where things go wrong. Shunts fail for three main reasons: age, voltage surges, and moisture. Over time, corrosion builds up on the shunt contacts. A power surge—even a minor one from turning on multiple appliances simultaneously—can weld the shunt shut prematurely or blow it open entirely. And if moisture seeps into outdoor-rated sockets (especially near tree branches or gutters), electrolytic corrosion prevents the shunt from activating when needed.

When shunts fail *open*, the circuit breaks at that bulb—and everything downstream goes dark. When they fail *closed* (shorted), the bulb may stay lit but draw excess current, overheating adjacent bulbs and cascading failures. This is why replacing one “dead” bulb sometimes causes two more to burn out within hours.

“The shunt was a brilliant engineering compromise—but it’s also the weakest link in vintage light strings. Its reliability drops over 70% after three seasons of outdoor use, especially in humid climates.” — Mark Delaney, Electrical Engineer & Former Product Lead, Holiday Light Labs

LED Strings: Different Wiring, Different Failures

Modern LED light strings behave very differently—not because LEDs are inherently more reliable, but because their circuitry is fundamentally re-engineered. Most LED mini-strings use constant-current drivers and IC-controlled segments. Instead of 50-bulb series chains, they’re often grouped into 3–6 bulb segments, each with its own current-limiting resistor and sometimes even a tiny microcontroller.

So why do *LED* strings also show “half-on” behavior? Not from open filaments—but from driver failure, segment-level voltage drop, or polarity-sensitive wiring. Because LEDs are diodes, they only conduct current in one direction. If the string uses a full-wave rectifier and one leg of the AC cycle fails (e.g., due to a blown capacitor in the driver), you’ll see dim or intermittent lighting—often appearing as “every other section” glowing faintly. Also, many LED strings rely on data lines (for color-changing models) or shared ground paths. A compromised ground connection can kill half the string while leaving the other half functional.

| Issue | Incandescent Strings | LED Strings |

|---|---|---|

| Most Common Cause of Half-Out | Open filament + failed shunt in first dead bulb of a series leg | Driver IC failure or voltage drop across long wire runs |

| Effect of One Bad Bulb | Entire series leg (often 50 bulbs) goes dark | Only that 3–6 bulb segment fails; rest unaffected |

| Fuse Location | Inside plug housing (two small glass fuses) | Rarely fused; protection built into driver board |

| Voltage Sensitivity | Tolerant of minor fluctuations (±15%) | Fail abruptly below 85% rated input voltage |

| Moisture Impact | Causes shunt corrosion → open circuit | Triggers short circuits on PCB → thermal shutdown |

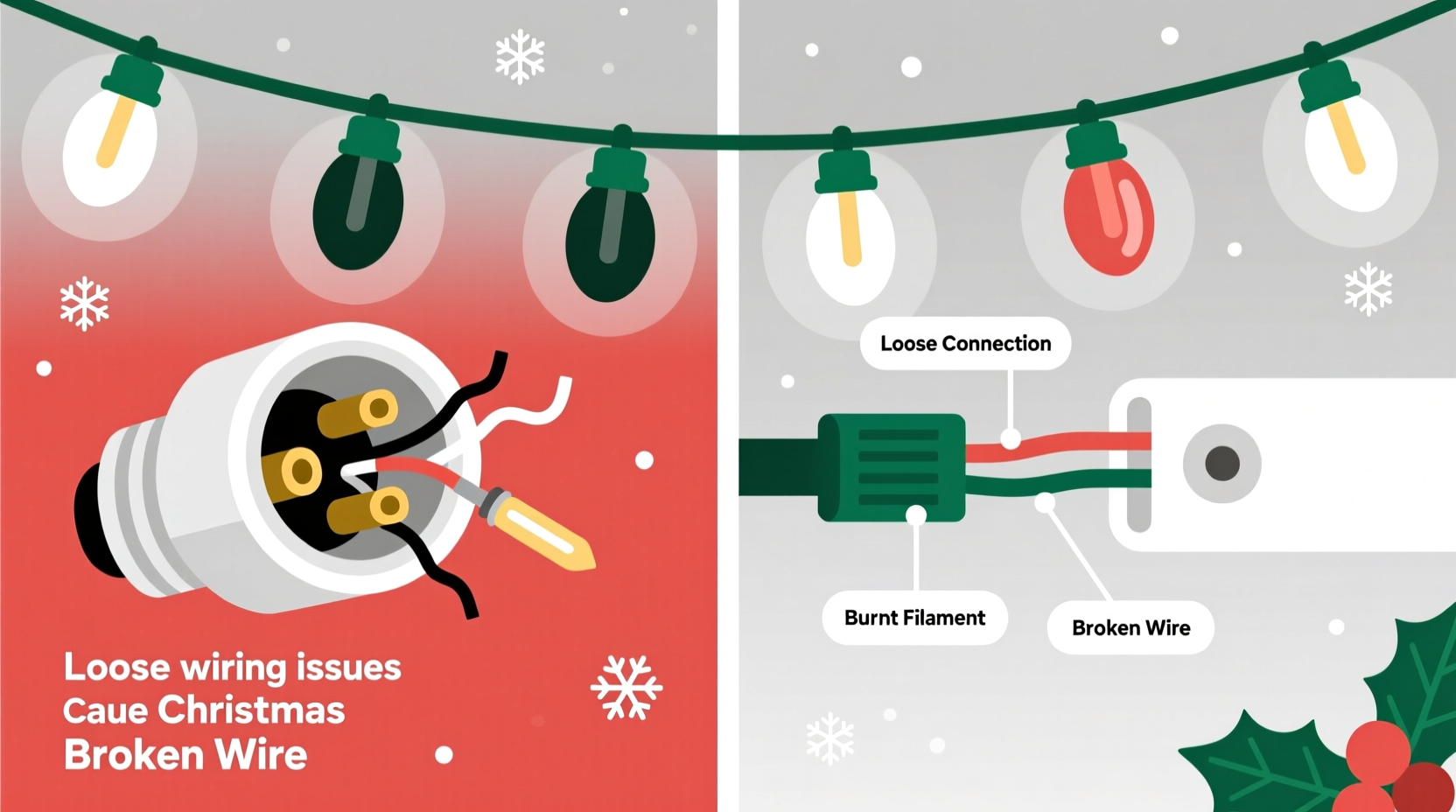

Connector & Plug Failures: The Hidden Weak Link

Between the plug and the first bulb lies the most abused part of any light string: the male/female connector pair. These molded plastic housings contain thin, crimped copper wires soldered to brass contacts. With repeated plugging/unplugging—and especially when yanked sideways instead of pulled straight—the internal wires fatigue and fracture. Since these connectors carry *full circuit current*, even a hairline break in the hot or neutral line will kill the entire downstream portion.

Worse, many budget strings use “daisy-chain” connectors rated for only 3–5 amps. When you connect five 100-light strings together, you’re pushing ~4.5 amps through a connector designed for a single string. Heat builds, contacts oxidize, resistance increases—and voltage drop begins. The result? The first string glows brightly; the third string is dim; the fifth string flickers or stays off. This isn’t a bulb issue—it’s an overloaded connection point.

Mini Case Study: The Porchlight Paradox

Janice in Portland strung 12 identical 100-light LED icicle lights along her porch eaves. She connected them end-to-end using the factory plugs. The first four strings worked perfectly. Strings 5–8 glowed at 60% brightness. Strings 9–12 wouldn’t light at all—even after swapping outlets and checking fuses. A technician arrived with a multimeter and tested voltage at each connector. At the plug of string #5: 118V. At the output of string #5’s female connector: 102V. At the input of string #9: 89V. The culprit? Two corroded, undersized connectors between strings #4 and #5—causing cumulative voltage drop. Replacing just those two connectors restored full brightness across all 12 strings. No bulbs were faulty. No fuses blown. Just degraded metal-to-metal contact.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol

Follow this sequence *in order*. Skipping steps leads to misdiagnosis and wasted time.

- Unplug and inspect the fuse. Remove the plug cover. Check both glass fuses for visible breaks or darkened glass. Replace with identical amperage (usually 3A or 5A). Never substitute with higher-rated fuses.

- Test continuity at the plug. Set multimeter to continuity mode. Touch probes to the two prongs of the plug. You should hear a beep. No beep = internal wire break in cord or plug.

- Locate the first dark bulb. Starting at the plug end, find the last bulb that lights. The problem is almost always *at or immediately after* that bulb.

- Check bulb fit and shunt (incandescent). Gently twist each bulb in the dark section. Use a bulb tester or swap in a known-good bulb. If the string lights, the original bulb had a failed shunt.

- Test voltage at key points (LED strings). With string plugged in, measure voltage between wires *just before* and *just after* the first dark segment. A >3V drop indicates failing driver or damaged trace on PCB.

- Inspect connectors under magnification. Look for green corrosion on brass contacts, melted plastic housing, or bent pins. Clean with electrical contact cleaner and a soft brass brush—not sandpaper.

FAQ

Can I cut and splice a broken Christmas light string?

Yes—but only if you understand the circuit topology. Cutting a series string mid-run creates two dead ends unless you reconfigure the wiring to maintain loop continuity. For LED strings, cutting often severs data lines or ground planes, requiring soldering and reprogramming. Unless you have electronics training, replacement is safer and more reliable.

Why do new light strings sometimes fail right out of the box?

Manufacturing defects account for ~12% of early failures—most commonly cold solder joints on driver boards (LED) or misaligned shunts (incandescent). Quality control varies widely by brand. Reputable brands like GE, NOMA, and Balsam Hill test at 130% rated voltage for 72 hours pre-shipment; budget imports often skip this step.

Is it safe to mix old and new light strings on one outlet?

No. Older incandescent strings draw significantly more current (up to 0.3A per 100 bulbs) than LED equivalents (~0.02A). Plugging both into the same circuit risks overloading the outlet’s 15A breaker—especially if other holiday devices (garland lights, inflatables) share the circuit. Always calculate total load: add watts of all connected devices and divide by 120V to get amps.

Conclusion

“Half-working” Christmas lights aren’t a mystery—they’re a diagnostic opportunity. Every dark bulb, flickering segment, or warm connector tells a story about voltage, resistance, and circuit integrity. Whether you’re dealing with vintage incandescent strings whose shunts have tired with age, or modern LED arrays where a single capacitor failure cascades across segments, the root cause is almost always traceable to one of five wiring realities: series circuit dependency, shunt degradation, driver limitations, connector fatigue, or cumulative voltage drop. Armed with a $20 multimeter, a bulb tester, and methodical testing, you can restore functionality without replacing the entire string—saving money, reducing waste, and keeping holiday traditions alive longer. Don’t treat your lights as disposable. Treat them as engineered systems worthy of thoughtful maintenance.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?