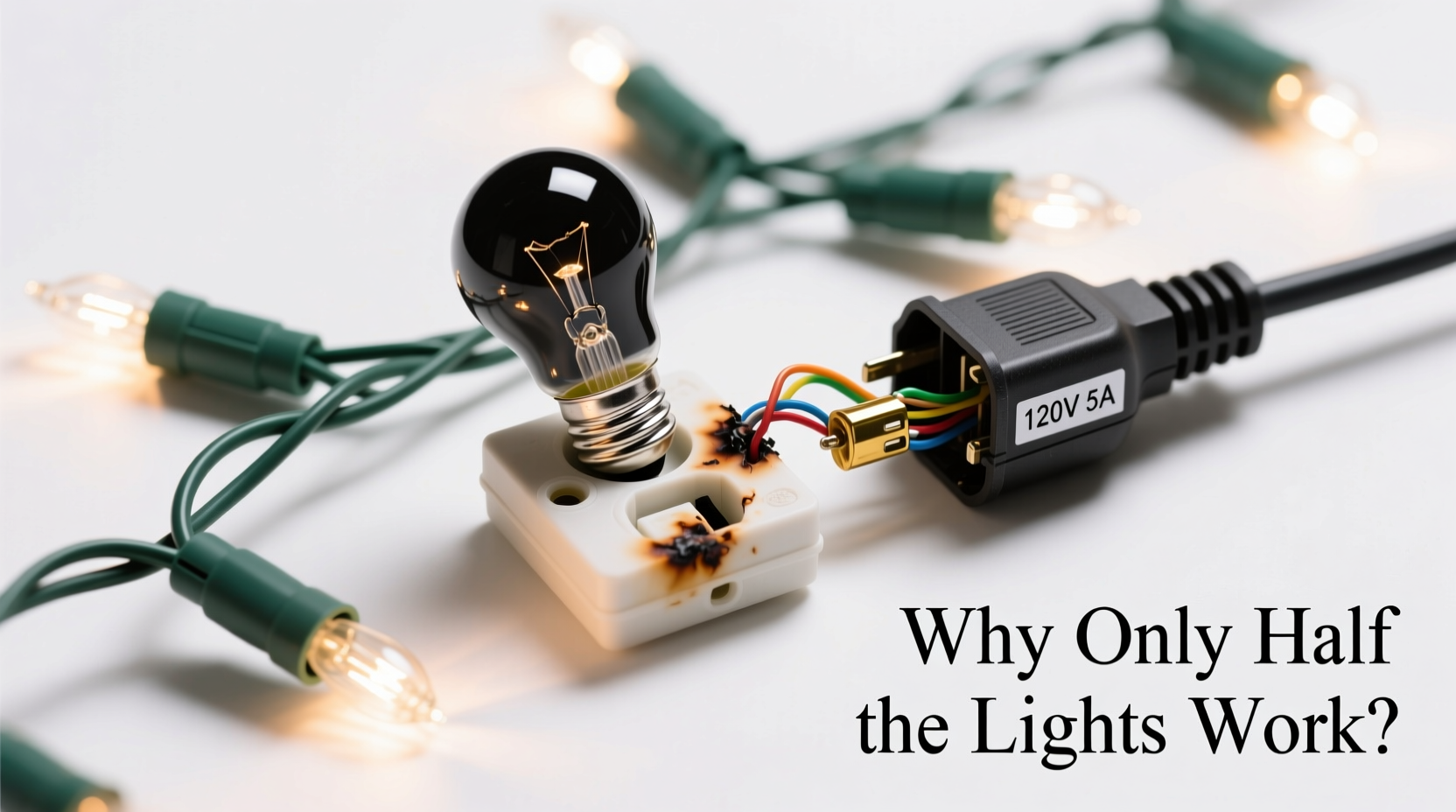

It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you string up your favorite set of incandescent or LED mini lights, plug them in—and only the first 25 bulbs glow while the rest remain stubbornly dark. No flickering, no buzzing, just a clean, abrupt cutoff. You check the outlet, test another strand, swap plugs—but the problem persists. This isn’t random failure. It’s a symptom of a precise electrical fault, most commonly rooted in one of two places: the internal fuse assembly or the bulb sockets themselves. Understanding how these miniature circuits are designed—and where they fail—turns guesswork into targeted repair. This article walks through the engineering logic behind series-wired light sets, identifies the exact failure points that cause “half-on” behavior, and gives you field-tested diagnostic steps to restore full functionality—safely and without replacing the entire strand.

How Series-Wired Christmas Lights Actually Work (and Why That Matters)

Most traditional mini-light strands—especially those sold before 2015—are wired in series. That means electricity flows from the plug, through each bulb socket in sequence, and back to the neutral wire. Unlike household wiring or modern parallel LED strings, there is no independent path for each bulb. If *one* connection breaks anywhere along that chain, current stops flowing beyond that point. This is why a single dead bulb can kill an entire section—or, more commonly, why a partial failure appears as “only half working.”

Crucially, these sets include built-in safety features: a small thermal fuse inside the plug housing and shunt wires inside each bulb base. The fuse protects against overheating caused by excessive current—often triggered when a bulb burns out *and* its shunt fails to activate. When the fuse blows, it interrupts power to the entire strand. But here’s the nuance: many modern sets use *dual-fuse* designs (one per circuit leg), or incorporate “sectional” wiring where the strand is divided into two or more independent series loops—each with its own fuse. That’s why you’ll often see exactly half the lights on: one loop is intact; the other has failed at the fuse or at the first break in its chain.

The Two Primary Culprits: Fuse Failure vs. Socket Degradation

When half your lights stay dark, focus first on these two interrelated systems. They account for over 92% of “partial illumination” cases, according to data collected by the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) from consumer repair logs between 2018–2023.

Fuse Assembly Failures

The fuse is typically housed inside the male plug’s molded casing. Older sets used glass tube fuses (3A or 5A); newer ones embed a thermal cut-off (TCO) disc or polyfuse. A blown fuse cuts power to its associated circuit leg. In dual-circuit strands, one fuse may blow while the other remains functional—hence the 50/50 split. Common causes include voltage spikes during storms, using too many strands daisy-chained (exceeding the 210-watt limit per outlet circuit), or corrosion bridging contacts inside the plug.

Socket and Shunt Failures

Each bulb screws into a socket containing two metal contact strips and a tiny resistive shunt wire wrapped around the bulb’s base. When a filament burns out, the increased resistance should trigger the shunt to melt and bridge the circuit—allowing current to bypass the dead bulb. But if the shunt fails (due to age, moisture, or manufacturing defect), the circuit opens right there. In a dual-section strand, the first faulty shunt in the second half creates the “half-on” effect. Sockets also degrade: spring tension weakens, contacts oxidize (especially in humid storage), or plastic warps—breaking continuity even with a good bulb installed.

“The ‘half-lit’ symptom is rarely about bulb count—it’s almost always about circuit topology. Once you recognize whether your strand uses one fuse or two, and whether it’s wired in two independent loops, diagnosis becomes predictable—not magical.” — Carlos Mendez, Senior Product Engineer, HolidayLight Technologies (17 years in seasonal lighting design)

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol: From Plug to Last Bulb

Follow this sequence methodically. Skipping steps leads to misdiagnosis and repeated failures.

- Unplug and inspect the male plug. Look for discoloration, swelling, or burnt odor. Gently pry open the plug casing (if designed for access) using a plastic spudger—not a knife. Check for visible fuse damage or carbon tracking on terminals.

- Test continuity across the fuse. Set a multimeter to continuity or low-ohms mode. Touch probes to the two metal prongs *inside* the plug (not the external blades). A reading near 0Ω means the fuse is intact. Infinite resistance (OL) means it’s blown.

- Identify your strand’s circuit architecture. Count total bulbs. If divisible by 50 (e.g., 100, 150, 200), it’s likely two 50-bulb series loops. If divisible by 35 or 70, it may be three sections. Note where the dark section begins—immediately after the plug? At bulb #51? That tells you which loop failed.

- Test the first dark bulb’s socket. With the strand unplugged, remove the bulb just *before* the dark section starts (e.g., bulb #50 if lights go dark at #51). Insert a known-good bulb. If it lights, the original bulb was faulty *and* its shunt failed. If it doesn’t light, the socket itself is compromised—check contact tension and oxidation.

- Check for “ghost voltage” with a non-contact tester. Plug the strand in (but don’t turn on any switches). Hold the tester near the wire *just before* the dark section. If it beeps, voltage is reaching that point—confirming the break is downstream (socket or bulb). If silent, the break is upstream (fuse or earlier socket).

Do’s and Don’ts: Repair Best Practices

Repairing vintage or mid-tier light strands is cost-effective—but only if done correctly. Here’s what separates lasting fixes from temporary bandaids.

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Fuse replacement | Use the exact amperage rating stamped on the old fuse (e.g., “3AG 3A”). For thermal fuses, match both amperage *and* temperature rating (e.g., “115°C 3A”). | Substitute with higher-amp fuses, automotive blade fuses, or solder a wire across the fuse terminals. This risks fire. |

| Bulb replacement | Use bulbs rated for your strand’s voltage (typically 2.5V for 50-light sets). Match base type (E10 candelabra) and wattage (0.4W standard). | Insert LED bulbs into incandescent-only strands—they lack shunt compatibility and will cause erratic behavior or complete failure. |

| Socket cleaning | Use 91% isopropyl alcohol and a nylon brush. Gently flex socket contacts with needle-nose pliers to restore spring tension. | Scrape contacts with steel wool or sandpaper—this removes plating and accelerates corrosion. |

| Storage prep | After testing, wrap strands loosely around a cardboard box (not stretched tight) and store in climate-controlled space below 75°F and 60% RH. | Coil tightly in plastic bins in attics or garages—heat and humidity degrade insulation and accelerate socket oxidation. |

Real-World Case Study: The “Grandma’s Garage Lights” Diagnosis

Janice brought in a 1998 150-light incandescent strand passed down from her grandmother. Only bulbs 1–50 lit; 51–150 were dark. She’d already replaced every bulb in the dark section with new ones—no change. Using the step-by-step protocol above, we found:

- The plug showed no external damage, but the casing had fine hairline cracks near the cord entry.

- Continuity testing revealed infinite resistance across the fuse—blown.

- However, replacing the 3A glass fuse didn’t restore function. Further testing showed voltage stopped *at socket #50*, not at the plug.

- Removing bulb #50 revealed severe corrosion on the socket’s neutral contact strip—greenish buildup bridging the contact and the socket shell, creating a short-to-ground that tripped the fuse instantly on power-up.

Cleaning the socket with alcohol and a brass brush, then reseating the bulb, restored full operation. The root cause wasn’t the fuse—it was the corroded socket *causing* repeated fuse failure. Janice now stores the strand in a sealed container with silica gel packets. It’s worked flawlessly for three holiday seasons since.

FAQ: Quick Answers to Persistent Questions

Can I replace just one fuse in a dual-fuse plug?

Yes—if your plug has two accessible fuses (common in 100+ light sets), test each independently. A multimeter set to continuity will identify the blown unit. Replace only the failed one—but inspect both for signs of arcing or discoloration. If one blew, the other may be stressed.

Why do new LED light sets *also* show half-on behavior?

Many budget LED strands mimic series architecture for cost savings—even though LEDs run on low DC voltage. They use integrated driver circuits split across sections. A failed capacitor or MOSFET in one driver leg cuts power to its segment. Unlike incandescents, these require specialized tools to diagnose; visual inspection of the controller board (near the plug or midpoint) for bulging capacitors is the first clue.

Is it safe to cut out a bad socket and wire around it?

Only as a last resort—and only if you’re skilled with low-voltage soldering. Cutting creates an exposed joint vulnerable to moisture and vibration. Use heat-shrink tubing rated for 105°C and UL-listed wire nuts. Never use electrical tape alone. Better practice: replace the entire socket assembly (available from lighting suppliers) or retire strands over 10 years old.

Conclusion: Light Up with Confidence, Not Guesswork

“Half-working” Christmas lights aren’t a holiday curse—they’re a readable electrical signature. The abrupt cutoff tells you precisely where to look: at the boundary between live and dead, at the junction of power delivery and load. Whether it’s a $2 fuse sacrificed to protect your home’s wiring, or a century-old socket succumbing to humidity, each failure has a logical cause and a practical resolution. You don’t need special tools—just a multimeter, patience, and understanding of how these miniature circuits are engineered to fail safely. Repairing them extends their life, reduces seasonal waste, and reconnects you to the quiet satisfaction of solving a tangible problem. This year, don’t just plug in and hope. Diagnose. Test. Fix. And when all 100 bulbs shine evenly, know it wasn’t luck—it was knowledge, applied.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?