Labor Day is more than just a long weekend or the unofficial end of summer. It is a national observance rooted in struggle, solidarity, and social progress. While many Americans spend the day barbecuing or shopping, few pause to consider the deeper historical currents that led to its creation. Understanding why we celebrate Labor Day requires a journey into the late 19th century—a time when industrialization was reshaping American life, often at great human cost. This article explores the origins, evolution, and enduring meaning of Labor Day, offering insight into how it became a symbol of workers' dignity and rights.

The Origins of Labor Day: A Movement Born from Struggle

In the decades following the Civil War, the United States experienced rapid industrial expansion. Factories, railroads, and mines boomed, but working conditions were often brutal. Employees—including children—routinely labored 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week, for meager wages. Safety regulations were nearly nonexistent, and job-related injuries and deaths were common.

As discontent grew, workers began organizing into labor unions to demand better pay, shorter hours, and safer environments. One of the earliest and most influential groups was the Knights of Labor, which advocated for an eight-hour workday and equal treatment for all workers regardless of gender or race. These movements laid the foundation for what would become Labor Day.

The first Labor Day celebration occurred on **September 5, 1882**, in New York City. Organized by the Central Labor Union and supported by the Knights of Labor, the event featured a parade of over 10,000 workers who marched from City Hall to Union Square. They carried banners declaring “Labor Creates All Wealth” and “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for Recreation.” The demonstration was peaceful but powerful—a public assertion of workers’ value and unity.

From Protest to Public Holiday: The Road to Federal Recognition

Following the success of the 1882 parade, the Central Labor Union established an annual tradition. By 1887, several states—including Oregon, Colorado, and New York—had officially recognized Labor Day as a state holiday. Momentum continued to build as more unions and civic leaders pushed for national recognition.

The turning point came during a period of intense labor unrest. In 1894, the Pullman Strike paralyzed much of the nation’s railroad system. Workers at the Pullman Company in Chicago walked off the job to protest wage cuts while rent in company-owned housing remained unchanged. President Grover Cleveland ordered federal troops to break the strike, leading to violence and dozens of deaths.

The backlash against the government’s harsh response pressured Congress to act. Just days after the strike was suppressed, lawmakers rushed to pass legislation making Labor Day a federal holiday. On **June 28, 1894**, President Cleveland signed the bill into law, designating the first Monday in September as a national day to honor workers.

“Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed.” — Abraham Lincoln, 1861

What Does Labor Day Symbolize Today?

Over time, the radical roots of Labor Day have softened in public memory. For many, it marks the end of summer, a final chance to grill, travel, or shop during holiday sales. Yet its symbolic weight remains significant. Labor Day serves as both a celebration and a reminder:

- A recognition of the economic and social contributions of American workers.

- A tribute to the labor movement’s role in securing fundamental rights like weekends, minimum wage, and workplace safety.

- A moment to reflect on ongoing challenges, including income inequality, gig economy precarity, and union decline.

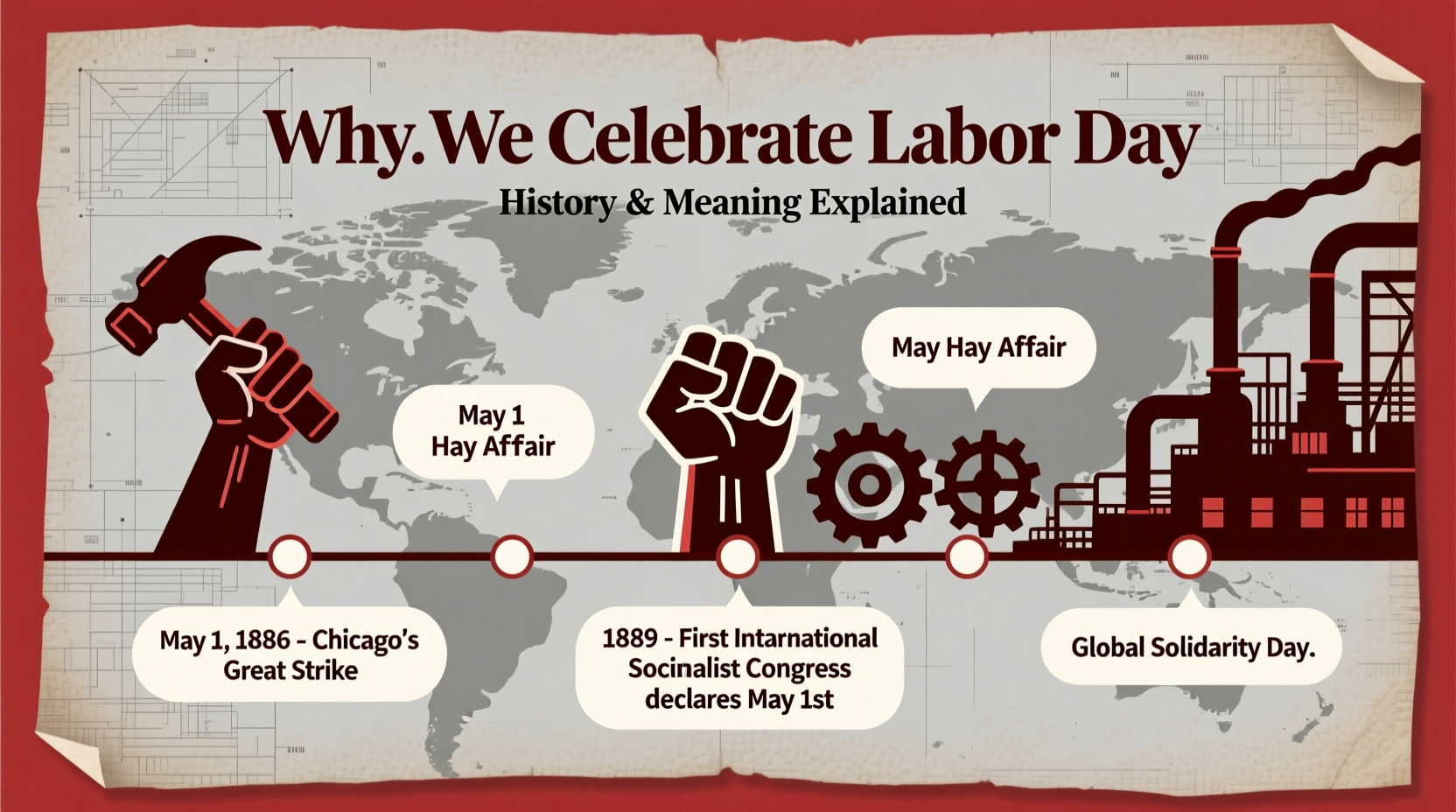

Unlike May Day (International Workers’ Day), which is celebrated in over 80 countries on May 1st and often associated with political demonstrations, U.S. Labor Day was deliberately placed in September to distance it from radical socialist associations. Still, the spirit of solidarity persists in parades, union gatherings, and community events held across the country.

Key Achievements Linked to the Labor Movement

| Reform | Year Enacted | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Eight-Hour Workday Standard | 1938 (Fair Labor Standards Act) | Established maximum work hours and overtime pay. |

| Social Security Act | 1935 | Provided retirement and unemployment benefits. |

| Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) | 1970 | Mandated safe working conditions nationwide. |

| Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) | 1993 | Guaranteed unpaid leave for medical and family reasons. |

How to Honor Labor Day Meaningfully

While relaxing is perfectly valid, there are ways to observe Labor Day that acknowledge its historical significance. Consider these actions to deepen your appreciation:

- Learn about local labor history—Visit a museum, read about influential strikes, or explore union archives online.

- Support union-made products—From clothing to coffee, many brands proudly label their goods as union-produced.

- Attend a Labor Day event—Parades and rallies still occur in cities like Detroit, Milwaukee, and San Francisco.

- Advocate for fair labor practices—Contact representatives about issues like paid family leave or raising the minimum wage.

- Thank essential workers—Recognize those who keep society running, from healthcare staff to transit operators.

Mini Case Study: The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

No discussion of labor history is complete without mentioning the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City. On March 25, 1911, a blaze broke out in a garment factory where doors were locked to prevent theft and unauthorized breaks. Trapped inside, 146 workers—mostly young immigrant women—perished, some jumping to their deaths to escape the flames.

The tragedy shocked the nation and became a catalyst for reform. In the aftermath, new fire safety laws were enacted, and labor unions gained momentum advocating for protective legislation. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) used the incident to rally support, emphasizing that worker safety was not a privilege but a right.

Today, the site is marked by a memorial, and the event is commemorated annually. It stands as a grim reminder of what happens when profit overrides people—and why holidays like Labor Day matter.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Labor Day in September instead of May?

The U.S. chose September to avoid association with May 1st, which is tied to the Haymarket Affair of 1886 and international socialist movements. Leaders wanted a less politically charged date.

Do other countries celebrate Labor Day the same way?

No. Most nations observe International Workers’ Day on May 1st with marches and political rallies. Canada also celebrates Labor Day in September, following a similar historical path as the U.S.

Is Labor Day only for union workers?

No. While the holiday emerged from union activism, it honors all workers—waged, salaried, part-time, and self-employed. Its legacy belongs to anyone who contributes through labor.

Conclusion: More Than a Day Off

Labor Day is not merely a seasonal marker or retail occasion. It is a testament to decades of advocacy, sacrifice, and perseverance by ordinary people demanding dignity in their work. From the streets of 1882 New York to modern debates about automation and equity, the labor movement continues to shape the contours of American life.

As you enjoy your holiday weekend, take a moment to reflect on the hands that built the bridges, stitched the clothes, taught the children, and cared for the sick. Their struggles made possible the rights many now take for granted. Let Labor Day be not just a pause, but a promise—to remember, respect, and renew our commitment to fairness in the world of work.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?