DNA—the blueprint of life—carries the genetic instructions used in the development, functioning, and reproduction of all known living organisms. At the heart of this biological marvel lies a deceptively simple yet profoundly elegant shape: the double helix. This twisted-ladder structure isn’t just visually striking; it’s fundamental to how life stores, copies, and transmits information. But why did evolution settle on this specific form? What advantages does the double helix offer over other possible configurations? Understanding the reasons behind DNA’s iconic shape reveals deep insights into the mechanics of life itself.

The Discovery That Changed Biology

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick published their groundbreaking model of DNA’s structure, based in part on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray diffraction images. Their revelation—that DNA forms a double helix—revolutionized biology. The model showed two complementary strands winding around each other, held together by hydrogen bonds between nitrogenous bases. This was more than a structural curiosity; it immediately suggested a mechanism for replication. If each strand could serve as a template for a new partner, genetic information could be faithfully copied during cell division.

“Watson and Crick’s model didn’t just describe a molecule—it revealed a machine capable of self-replication.” — Dr. Evelyn Reed, Molecular Biologist, MIT

Functional Advantages of the Double Helix

The double helix isn’t arbitrary. Its architecture provides several critical functional benefits that make life as we know it possible:

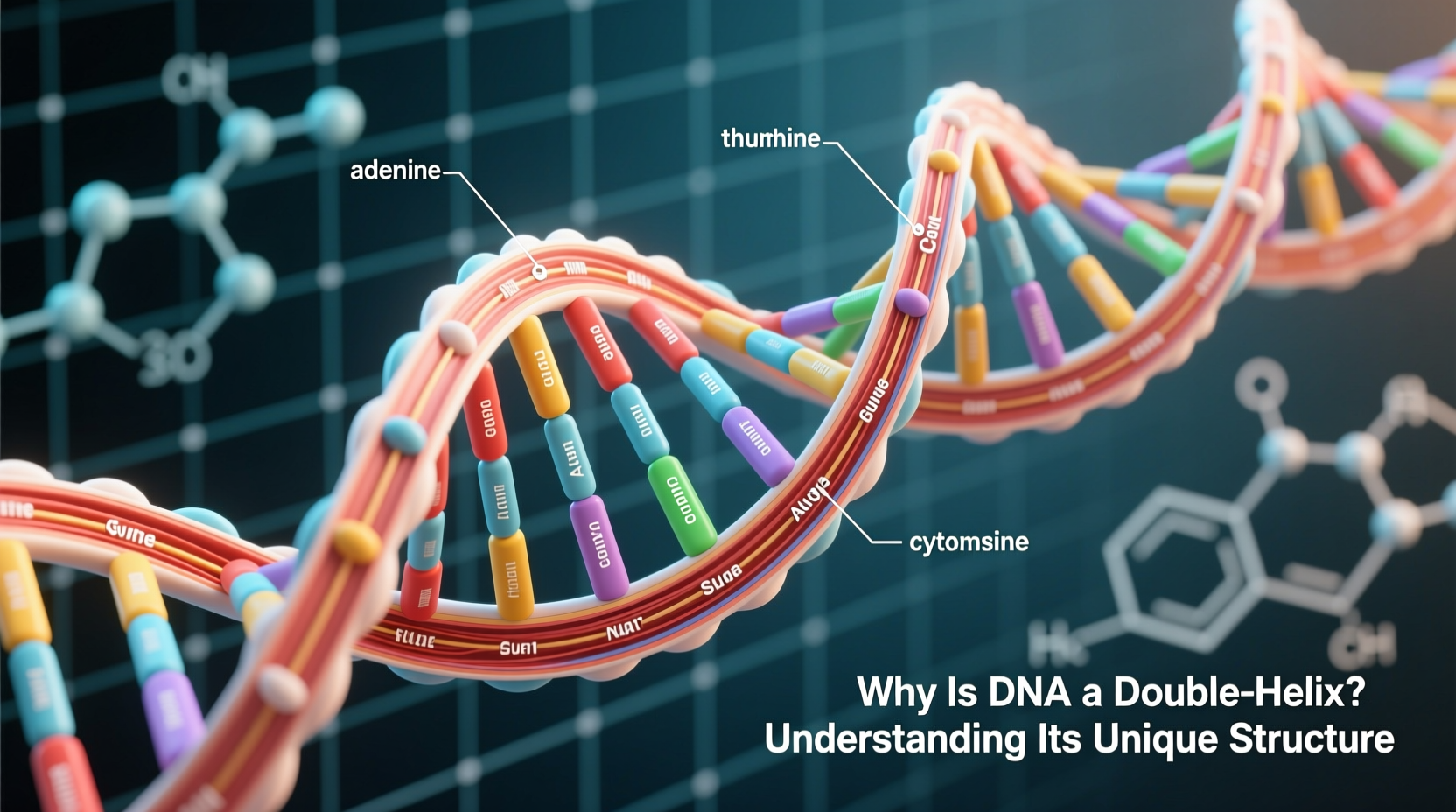

- Stability through base stacking: The flat nitrogenous bases (adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine) stack like pancakes in the core of the helix. This stacking minimizes exposure to water and provides hydrophobic stability, reinforcing the molecule’s integrity.

- Protection of genetic code: The sugar-phosphate backbones run along the outside, forming a protective shell around the inner base pairs where genetic information is stored. This shields the delicate coding sequence from chemical damage.

- Controlled access for proteins: The grooves of the helix—major and minor—allow regulatory proteins and enzymes to recognize specific sequences without unwinding the entire molecule.

- Efficient packing: The helical twist allows DNA to coil tightly around histone proteins, enabling meters of genetic material to fit inside microscopic cell nuclei.

Mechanics of Replication: Why Two Strands Matter

One of the most compelling reasons for the double helix is its role in replication. Because the two strands are complementary—A always pairs with T, C with G—each can act as a template for a new strand. When a cell prepares to divide, enzymes called helicases unwind the helix, breaking hydrogen bonds between base pairs. DNA polymerase then moves along each exposed strand, adding nucleotides according to base-pairing rules.

This semi-conservative method ensures that each new DNA molecule contains one original strand and one newly synthesized strand, preserving genetic fidelity across generations. Without two complementary strands, such a precise copying mechanism would be impossible.

Step-by-Step: How DNA Replicates

- Helicase unwinds the double helix at a replication fork.

- Single-strand binding proteins stabilize the separated strands.

- Primase synthesizes a short RNA primer to initiate replication.

- DNA polymerase adds nucleotides in the 5’ to 3’ direction.

- Ligase seals gaps between Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand.

- Two identical double helices are formed, each with one old and one new strand.

Structural Resilience and Error Correction

The double helix also plays a crucial role in maintaining genetic accuracy. Mismatched base pairs distort the regular geometry of the helix, making them easier for repair enzymes to detect. For example, if guanine mistakenly pairs with thymine, the irregular spacing disrupts the smooth twist of the backbone. Proteins like MutS scan the DNA for these kinks and initiate correction pathways.

Beyond repair, the double-stranded nature allows redundancy. If one strand suffers damage—say, from UV radiation or chemical mutagens—the intact complementary strand can serve as a reference for restoration. This error-correction system reduces mutation rates and enhances evolutionary fitness.

| Feature | Role in Double Helix Function |

|---|---|

| Complementary Base Pairing | Enables accurate replication and transcription |

| Antiparallel Strands | Allows directional synthesis by DNA polymerase |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Strong enough to hold strands together, weak enough to allow separation |

| Major and Minor Grooves | Provide binding sites for transcription factors and regulatory proteins |

| Helical Twist | Facilitates supercoiling and chromatin packaging |

What If DNA Weren’t a Double Helix?

Consider alternative structures. A single-stranded DNA might store information but would lack stability and replication fidelity. Triple helices, while observed in rare synthetic or regulatory contexts, are less efficient and more prone to interference. Branched or linear non-helical forms would struggle with compaction and enzymatic access.

Nature tested various configurations early in evolution. RNA, likely the precursor to DNA, often folds into complex shapes—but its single-stranded nature makes it more reactive and less stable. DNA’s double helix represents an evolutionary optimization: maximum information density, chemical resilience, and replicative precision in a compact form.

Mini Case Study: The Role of Helix Geometry in Disease

In Huntington’s disease, a segment of DNA contains an abnormally long repetition of the CAG sequence. These repeats cause the double helix to form unusual secondary structures—like hairpins—during replication. Because the helix temporarily deviates from its standard form, DNA polymerase can “slip,” adding even more repeats in successive generations. This structural instability illustrates how deviations from ideal helical geometry can have devastating consequences. Understanding these anomalies helps researchers design therapies targeting DNA conformation, not just sequence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why doesn’t DNA use a triple helix instead?

A triple helix would increase stability but reduce flexibility and accessibility. Enzymes responsible for replication and transcription require the ability to separate strands easily. The energy cost of unwinding three strands would be prohibitively high, slowing down essential cellular processes.

Can DNA exist in forms other than the double helix?

Yes. Under certain conditions, DNA can adopt alternative conformations such as Z-DNA (a left-handed helix), cruciform structures, or G-quadruplexes. These are typically transient and play roles in gene regulation, but they’re exceptions that prove the rule: the right-handed B-form double helix remains the standard for stable genetic storage.

Is the double helix found in all organisms?

Virtually all cellular life uses double-helical DNA. Some viruses store genetic information in single-stranded DNA or RNA, but they rely on host cells to convert these into double-stranded intermediates for replication. The universality of the double helix underscores its evolutionary success.

Conclusion: Embracing the Elegance of Molecular Design

The double helix is more than a symbol of modern biology—it’s a masterpiece of natural engineering. Its structure balances stability with accessibility, permanence with adaptability, simplicity with sophistication. From the precise alignment of base pairs to the graceful twist of its backbone, every aspect serves a purpose. By understanding why DNA is a double helix, we gain deeper appreciation for the ingenuity embedded in every living cell.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?