Baking bread at home should be a rewarding experience—golden crust, soft crumb, that unmistakable aroma filling the kitchen. But when your dough refuses to rise, it can feel like a mystery with no solution. While many assume yeast is the culprit, the real answer often lies in something more subtle: your kitchen’s temperature. Understanding how ambient heat, humidity, and thermal consistency affect fermentation is essential to mastering homemade bread. This guide dives deep into the science of dough rise, highlights common environmental pitfalls, and provides actionable strategies to create the ideal proofing environment—even in less-than-perfect kitchens.

The Science Behind Dough Rising

Dough rises because of fermentation—a biological process driven by yeast. When active dry or fresh yeast is mixed with flour, water, and sugar, it consumes carbohydrates and releases carbon dioxide gas. These tiny bubbles get trapped in the gluten network, causing the dough to expand. This process doesn’t happen uniformly; it depends heavily on external conditions, especially temperature.

Yeast is a living organism, and like all organisms, its metabolic rate increases with warmth. In cooler environments, yeast activity slows dramatically. Below 60°F (15°C), most strains become nearly dormant. At temperatures above 90°F (32°C), yeast thrives—but only up to a point. Exceeding 120°F (49°C) begins to kill the yeast, halting fermentation entirely.

“Temperature isn’t just a background factor in bread baking—it’s a primary ingredient.” — Dr. Linda Collister, Artisan Bread Scientist

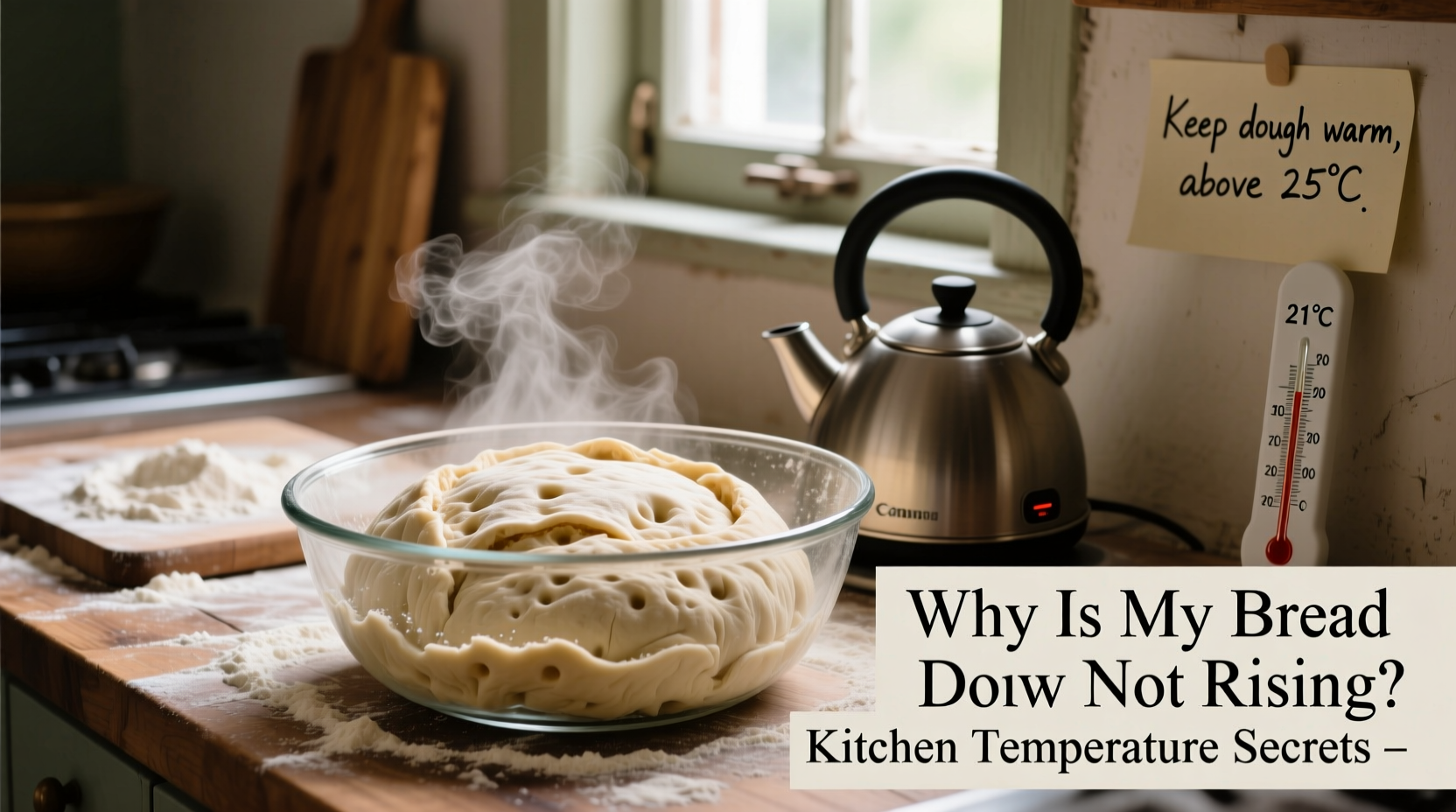

The ideal range for bulk fermentation (first rise) is between 75°F and 78°F (24°C–26°C). This allows steady gas production without over-acidifying the dough. A second proof, after shaping, benefits from slightly warmer conditions—around 80°F (27°C)—to encourage final expansion before baking.

How Kitchen Temperature Impacts Fermentation

Most home kitchens fluctuate in temperature due to seasonal changes, HVAC systems, or proximity to windows and appliances. These shifts may seem minor but have outsized effects on dough development.

In winter, indoor heating creates dry, warm air near vents but leaves corners and countertops cold. Placing dough near a drafty window or unheated wall can drop its surface temperature enough to stall fermentation. Conversely, summer kitchens often exceed 85°F (29°C), accelerating yeast activity and risking over-proofing—where dough collapses due to weakened gluten structure.

Humidity also plays a role. Dry air causes dough surfaces to form a skin, inhibiting expansion. High humidity can encourage mold growth during long ferments. Ideal relative humidity for proofing is between 75% and 80%.

Real Example: The Cold Countertop Dilemma

Sarah, an enthusiastic home baker in Minneapolis, struggled for months with dense sourdough loaves. Her starter bubbled vigorously, her technique was sound, yet her dough barely doubled overnight. After tracking her kitchen temperature, she discovered her granite countertop—though room-temperature to touch—was pulling heat from the dough. By placing the bowl inside a turned-off oven with a bowl of hot water beside it, she created a stable microclimate. Within days, her loaves achieved proper volume and open crumb structure.

Common Mistakes That Hinder Dough Rise

While temperature is critical, several related factors compound the problem when overlooked:

- Cold ingredients: Using refrigerated water, milk, or butter lowers initial dough temperature, delaying yeast activation.

- Incorrect yeast storage: Old or improperly stored yeast loses potency. Always store yeast in the freezer for long-term viability.

- Over-flouring: Excess flour absorbs moisture and restricts gluten elasticity, limiting expansion.

- Sealing dough too tightly: Covering dough with plastic wrap pressed directly onto the surface prevents upward movement.

- Using metal bowls near electronics: Some report electromagnetic interference from nearby devices subtly affecting fermentation—though anecdotal, it's worth considering in persistent failure cases.

| Kitchen Temp (°F) | Effect on Dough | Rise Time Estimate (vs. Ideal) |

|---|---|---|

| < 60°F (15°C) | Yeast dormant; minimal rise | 4+ hours or no rise |

| 65–70°F (18–21°C) | Slow fermentation; tangier flavor | 2–3x longer than normal |

| 75–78°F (24–26°C) | Optimal rise; balanced flavor | Standard timing (1.5–2 hrs) |

| 80–85°F (27–29°C) | Faster rise; risk of over-proofing | 50–70% of standard time |

| > 90°F (32°C) | Yeast stressed; possible death | Unpredictable; often fails |

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating the Perfect Proofing Environment

You don’t need a professional proofer to achieve consistent results. Follow this timeline-based method to control your kitchen climate effectively:

- Measure current conditions: Use a digital thermometer and hygrometer to record air and countertop temperature where dough will rest.

- Warm ingredients: Heat water or milk to 85°F (29°C) before mixing. Avoid exceeding 110°F (43°C) to protect yeast.

- Choose the right vessel: Use a large glass or ceramic bowl, which retains heat better than metal or plastic.

- Create a warm enclosure: Place the covered bowl inside a turned-off oven with a pan of boiling water on the rack below. Replace water every 30 minutes if proofing longer than 2 hours.

- Monitor progress: Check dough every 30–45 minutes. It should feel airy and spring back slowly when poked. If it collapses, it’s over-proofed.

- Adjust for second proof: After shaping, use the same setup but reduce water refills to maintain a slightly lower humidity level, preventing stickiness.

- Preheat strategically: Only turn on the oven once proofing is complete. Sudden heat exposure kills yeast and ruins structure.

Checklist: Ensure Your Kitchen Supports Proper Dough Rise

- ☐ Measure ambient temperature before starting

- ☐ Use lukewarm liquids (80–90°F / 27–32°C)

- ☐ Activate yeast properly (bloom in warm water with sugar for 5–10 mins if using dry yeast)

- ☐ Choose a draft-free spot away from windows and doors

- ☐ Cover dough loosely with damp cloth or oiled plastic wrap

- ☐ Test rise readiness with the finger poke test

- ☐ Maintain consistent warmth throughout fermentation

- ☐ Clean work surfaces to prevent bacterial competition with yeast

Expert-Backed Alternatives for Challenging Environments

Not every kitchen offers ideal conditions year-round. Experts recommend adaptive techniques based on real-world constraints:

For cold climates, bakers in Scandinavia often use “proofing boxes” made from insulated containers with LED-heated pads set to 77°F (25°C). These consume minimal energy and provide stable microclimates. Alternatively, placing dough near—but not on—a radiator wrapped in towels can gently elevate temperature.

In tropical regions, where kitchens regularly exceed 85°F (29°C), bakers slow fermentation by refrigerating dough immediately after mixing. This “cold bulk ferment” lasts 12–18 hours and develops superior flavor while avoiding over-proofing. The dough is then shaped and given a short final proof at room temperature before baking.

“In high heat, control comes from restraint. Cold fermentation gives you predictability and depth.” — Chef Rafael Mendez, Panadería Moderna, Mexico City

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use my microwave or oven light to proof dough?

Yes, but with caution. Turning on the oven light alone typically raises internal temperature to about 85°F (29°C)—ideal for faster proofing. However, never leave the heating element on. Microwaves can be used similarly: place a cup of boiling water inside, close the door, and let the residual steam and heat create a warm chamber. Do not operate the microwave while dough is inside.

My dough rose once but collapsed after shaping. What went wrong?

This usually indicates over-proofing during the first rise or excessive warmth during shaping. If dough doubles quickly in under an hour at room temperature, it’s likely too warm. Try reducing ambient temperature by moving to a cooler part of the kitchen or lowering liquid temperature by 5–10 degrees.

Does altitude affect dough rising?

Absolutely. At elevations above 3,000 feet (900 meters), lower atmospheric pressure allows gas bubbles to expand faster, speeding up rise times. Bakers at high altitudes often reduce yeast by 25%, decrease sugar slightly, and monitor dough closely to prevent collapse. Flour may also absorb less water, so hydration adjustments are common.

Final Tips for Consistent Success

Mastering dough rise isn’t about perfection—it’s about awareness. Pay attention to your kitchen’s rhythms: where sunlight falls in the afternoon, how heating cycles affect different zones, and how seasons shift your baseline conditions. Keep a simple log noting start time, ambient temperature, and rise duration. Over time, patterns emerge that help you anticipate rather than react.

Remember, great bread doesn’t require expensive tools. It requires observation, patience, and small adjustments guided by understanding. Whether you’re reviving a sluggish sourdough starter or troubleshooting a failed sandwich loaf, temperature remains the silent conductor of the entire process.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?