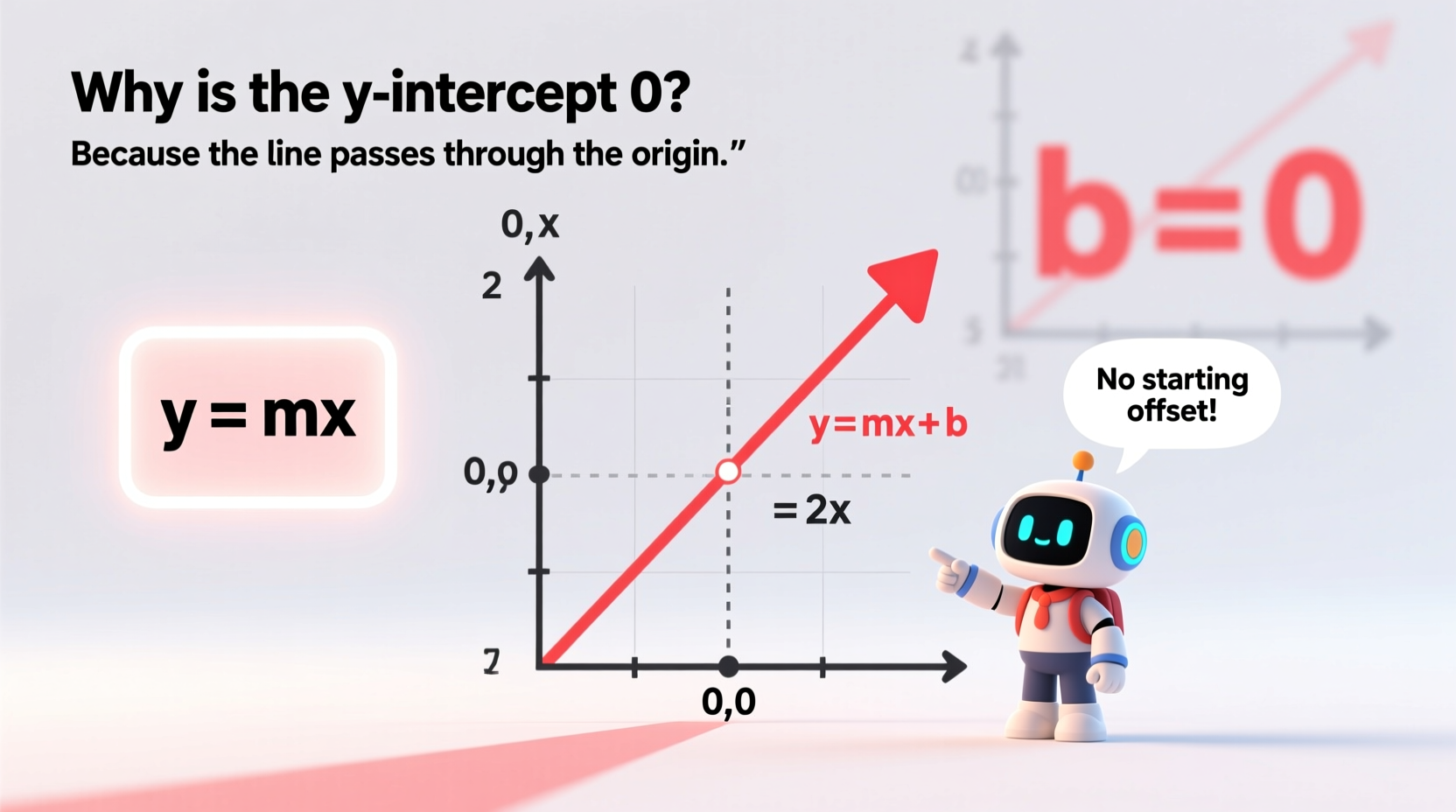

Linear equations form the foundation of algebra and are essential in modeling relationships between two variables. The general form, \\( y = mx + b \\), includes the slope (\\(m\\)) and the y-intercept (\\(b\\)), which is the value of \\(y\\) when \\(x = 0\\). While many real-world scenarios involve non-zero y-intercepts, there are important cases where setting the y-intercept to zero is not just convenient—it’s necessary. Understanding when and why this occurs deepens your grasp of both mathematics and its practical applications.

What the Y-Intercept Represents

The y-intercept marks the point where a line crosses the vertical axis on a graph. In practical terms, it reflects the starting value of a dependent variable when the independent variable is absent or at zero. For example, in a cost model, the y-intercept might represent a fixed fee before any units are produced. However, in situations where no such baseline exists, forcing the intercept to zero ensures the model aligns with reality.

Consider a car traveling at a constant speed. If you plot distance versus time, the relationship is linear. At time zero, the distance traveled must also be zero—assuming the measurement starts at the beginning of motion. A non-zero y-intercept would imply the car had already traveled some distance before the clock started, which contradicts the setup. This is a classic case where the y-intercept must be zero for logical consistency.

When Proportionality Demands a Zero Intercept

A key reason to set the y-intercept to zero arises when two variables are directly proportional. In direct proportionality, doubling one variable doubles the other, and this relationship only holds true when the line passes through the origin (0,0).

Mathematically, if \\( y \\propto x \\), then \\( y = kx \\), where \\(k\\) is the constant of proportionality. There is no \"+ b\" term because any addition would break the strict multiplicative relationship. Examples include:

- Distance traveled at constant speed: \\( d = vt \\)

- Force from a spring obeying Hooke’s Law: \\( F = kx \\)

- Ohm’s Law in electricity: \\( V = IR \\)

In each case, if the input is zero, the output must also be zero. No voltage without current, no force without displacement, no distance without time. These laws are defined by their adherence to proportionality—and thus require a zero y-intercept.

“Proportional relationships are foundational in physics and engineering. Ignoring the requirement for a zero intercept can lead to incorrect predictions and flawed designs.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Applied Mathematician

Statistical and Modeling Implications

In data analysis, especially regression modeling, choosing whether to include an intercept is a critical decision. While ordinary least squares (OLS) regression typically estimates both slope and intercept, there are scenarios where researchers deliberately suppress the intercept (i.e., force \\(b = 0\\)).

This approach, known as regression through the origin, is used when theoretical or empirical knowledge confirms that the response variable must be zero when the predictor is zero. However, doing so carelessly can distort results. For instance, forcing the intercept to zero when it shouldn’t be may inflate the \\(R^2\\) value artificially, giving a misleading impression of model fit.

| Scenario | Y-Intercept Should Be 0? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Weight of water vs. volume | Yes | No volume means no weight |

| Monthly salary vs. hours worked | No | Base salary may exist regardless of overtime |

| Electricity cost vs. kWh used | Sometimes | Only if no service fee applies |

| Revenue from ticket sales | Yes | No tickets sold = no revenue |

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

One common mistake is assuming all linear relationships must pass through the origin. In reality, many do not. For example, a person’s total monthly phone bill may include a base charge plus a per-minute rate. Even if they use zero minutes, they still pay the base fee—so the y-intercept is positive.

Another pitfall is forcing \\(b = 0\\) simply to simplify calculations. While it may make algebra easier, it risks misrepresenting the system being modeled. Always validate the assumption with context, not convenience.

Additionally, in experimental data, measurement error or systematic bias might make it appear that the line doesn’t pass through zero—even when theoretically it should. In such cases, statistical tests can help determine whether deviation from zero is significant or likely due to noise.

Mini Case Study: Fuel Consumption in a Test Vehicle

An automotive engineer is testing a new hybrid car's fuel efficiency. She records the amount of gasoline consumed over various distances driven under controlled conditions. Theoretically, if the car travels 0 miles, it should consume 0 gallons of gas. So, the model should follow \\( G = mD \\), where \\(G\\) is gallons used and \\(D\\) is distance.

However, initial regression analysis shows a small positive intercept—suggesting fuel use even at zero distance. Upon investigation, she discovers the fuel sensor has a calibration drift causing minor false readings at low consumption levels. By adjusting the data or using weighted regression through the origin, she corrects the model. The final equation, forced through zero, accurately reflects the physical reality and improves long-term predictive accuracy.

Step-by-Step Guide: Determining Whether the Y-Intercept Should Be Zero

- Define the Variables: Clearly identify what \\(x\\) and \\(y\\) represent in your scenario.

- Ask the Zero Question: If \\(x = 0\\), does it logically follow that \\(y = 0\\)?

- Check for Fixed Costs or Baselines: Are there inherent starting values (e.g., fees, initial states)?

- Review Scientific or Economic Laws: Does a known law (like Ohm’s or Hooke’s) govern the relationship?

- Analyze Data Patterns: Plot the data and observe behavior near the origin.

- Test Both Models: Fit both with and without an intercept; compare residuals and interpretability.

- Validate with Theory: Choose the model that best aligns with physical, economic, or logical principles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a linear equation have a zero y-intercept and still be realistic?

Yes, absolutely. Many natural and engineered systems exhibit direct proportionality. As long as the phenomenon starts from zero when the input is zero, a zero y-intercept is not only realistic but required for accuracy.

Does forcing the y-intercept to zero improve prediction accuracy?

Only if the underlying relationship truly passes through the origin. If not, forcing \\(b = 0\\) can introduce bias and reduce accuracy. Always base this decision on domain knowledge, not statistical convenience.

Is the slope affected when we set the y-intercept to zero?

Yes. When you remove the intercept, the slope is recalculated to minimize error around the origin. This often results in a different slope compared to a model with an estimated intercept. The new slope represents the average rate of change from zero onward, not adjusted for offset.

Actionable Checklist: Validating the Zero Intercept Assumption

- ☐ Confirm that zero input implies zero output in your context

- ☐ Review relevant scientific or economic principles

- ☐ Plot raw data and inspect behavior near (0,0)

- ☐ Compare R² and residual patterns between models with and without intercept

- ☐ Consult subject-matter experts if uncertain

- ☐ Avoid suppressing the intercept solely to achieve a higher R²

Conclusion: Aligning Math with Reality

The decision to set the y-intercept to zero is not arbitrary—it’s a reflection of how closely your mathematical model mirrors the real world. When variables are directly proportional or when no baseline offset exists, enforcing a zero intercept strengthens validity and enhances interpretability. But this choice must be grounded in logic, theory, or empirical evidence, not merely mathematical preference.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?