Lemons are among the most recognizable sour foods in the world. A single bite into a raw lemon can trigger an intense puckering sensation, tears in the eyes, and an immediate rush of saliva. But what exactly makes lemons so sour? Behind this sharp, mouth-puckering experience lies a complex interplay of chemistry, biology, and sensory perception. Understanding the science behind lemon sourness reveals not only how our bodies detect acidity but also why we’re evolutionarily wired to respond so strongly to it.

The Role of Citric Acid in Lemon Sourness

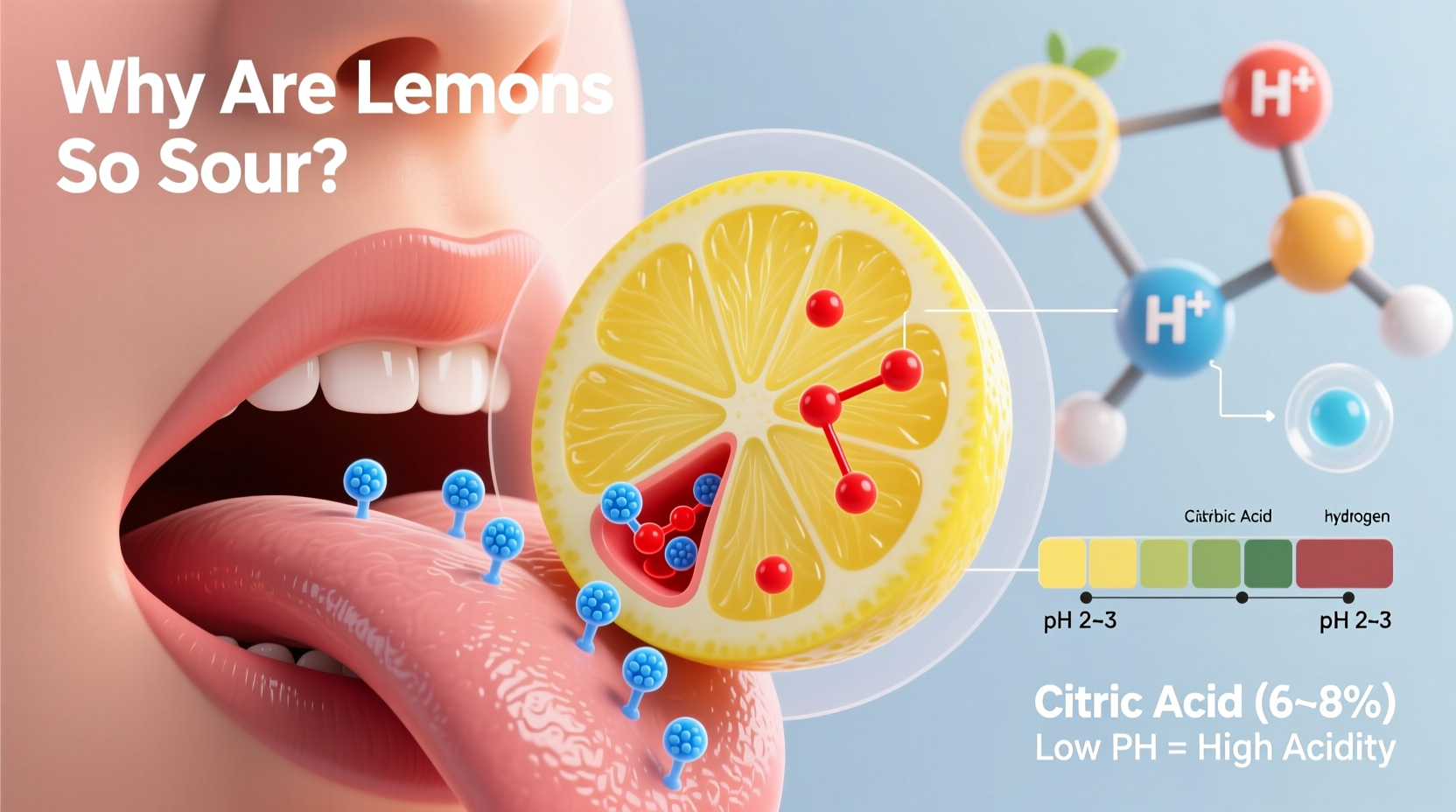

The primary reason lemons taste sour is their high concentration of citric acid. This organic compound makes up about 5% to 6% of the juice in a lemon by weight—far more than in most other fruits. Citric acid is a weak acid that dissociates in water, releasing hydrogen ions (H⁺) into the solution. It’s these free hydrogen ions that interact with our taste buds and signal sourness.

Citric acid plays multiple roles in plants. In citrus fruits like lemons, it helps regulate pH, supports energy production through the Krebs cycle, and acts as a natural preservative due to its low pH. The fruit accumulates citric acid during ripening, which peaks just before full maturity—making slightly underripe lemons even more acidic than fully ripe ones.

How Sour Taste Works: The Biology of Sour Detection

Sour taste is one of the five basic tastes recognized by science, alongside sweet, salty, bitter, and umami. Unlike sweetness—which signals energy-rich carbohydrates—sourness primarily detects acidity. Our ability to sense sour flavors is rooted in specialized taste receptor cells located within the taste buds on the tongue.

Recent research has identified specific ion channels involved in sour detection. One key player is the **OTOP1 proton channel**, discovered in 2018. When hydrogen ions from acidic substances like lemon juice enter the mouth, they flow through OTOP1 channels in taste cells, triggering an electrical signal sent to the brain. This process happens within milliseconds, explaining the near-instantaneous reaction we have when tasting something sour.

The evolutionary advantage of detecting sourness likely relates to food safety. Mild acidity often indicates freshness (e.g., ripe fruit), while excessive sourness may warn of spoilage or unripeness. However, humans have developed a cultural appreciation for sour flavors—from lemonade to fermented kimchi—suggesting that while sourness once served as a cautionary signal, it now contributes significantly to culinary enjoyment.

Comparing Acidity Levels: Lemons vs. Other Common Foods

To put lemon sourness into perspective, consider how its pH compares to other everyday foods. The lower the pH, the higher the acidity. Lemons typically have a pH between 2.0 and 2.6, placing them among the most acidic edible substances commonly consumed.

| Food / Beverage | Average pH | Acid Type |

|---|---|---|

| Lemon juice | 2.0–2.6 | Citric acid |

| Vinegar (acetic) | 2.4–3.4 | Acetic acid |

| Orange juice | 3.3–4.2 | Citric acid |

| Tomato juice | 4.1–4.6 | Citric & malic acids |

| Black coffee | 4.8–5.1 | Chlorogenic acid |

| Milk | 6.5–6.7 | Lactic acid (minimal) |

This table illustrates that few common foods approach the acidity of lemons. Even vinegar, known for its sharp tang, overlaps only at the upper end of lemon juice’s pH range.

Real-World Reaction: A Kitchen Experiment

Consider Maria, a home cook experimenting with flavor balancing in her new lemon tart recipe. She initially used the full amount of juice from two large lemons. Upon tasting the filling before baking, she experienced the classic physiological response: salivation surged, her lips pursed, and her face wrinkled instinctively. Recognizing this as a sign of excessive acidity, she adjusted the recipe by adding extra sugar and a pinch of salt. The final product was bright and zesty without being overwhelming.

This small example demonstrates how understanding sourness isn’t just academic—it directly impacts cooking outcomes. Chefs and bakers rely on the principle of flavor balance, where sour elements are offset by sweet, fatty, or salty components to create harmony on the palate.

“Sourness isn't just a taste—it's a physiological event. The body reacts to acidity with protective reflexes like salivation and facial grimacing, which help neutralize and expel potentially harmful substances.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Sensory Biologist at the Institute of Gustatory Research

Managing Sourness: Practical Tips for Cooking and Consumption

While lemons are prized for their vibrant flavor, their intensity can be managed effectively. Here are several strategies to harness their power without overwhelming your senses:

- Dilute lemon juice with water, oil, or other liquids when using in dressings or beverages.

- Balancing sour dishes with sweet ingredients like honey, maple syrup, or ripe fruit smooths harsh edges.

- Add salt in small amounts—it doesn’t eliminate sourness but reduces perceived acidity by modulating taste signals.

- Cooking lemon juice briefly can mellow its sharpness, though prolonged heat may reduce vitamin C content.

- Use zest instead of juice when you want citrus aroma without intense sourness.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lemon Sourness

Why do some people enjoy sour foods while others avoid them?

Tolerance for sour tastes varies widely due to genetics, cultural exposure, and personal experience. Some individuals have more sensitive sour-detecting pathways, making strong acidity uncomfortable. Others develop a preference over time, especially if sour flavors are associated with pleasurable experiences like refreshing drinks or gourmet cuisine.

Can eating too many lemons damage my teeth?

Yes. The high acidity of lemons can erode tooth enamel over time, increasing sensitivity and risk of cavities. To minimize harm, avoid swishing lemon water in your mouth, use a straw when drinking lemon-infused beverages, and wait at least 30 minutes before brushing your teeth after consuming acidic foods.

Is the sourness of a lemon related to its ripeness?

Generally, less ripe lemons are more sour because they contain higher levels of citric acid. As lemons ripen, acid levels decrease slightly while sugar content increases, leading to a more balanced flavor. However, even fully ripe lemons remain highly acidic compared to most fruits.

Conclusion: Embracing the Zest of Science and Flavor

The sour punch of a lemon is far more than a simple flavor—it’s a direct interaction between chemistry and biology. From the release of hydrogen ions to the activation of specialized taste receptors, every aspect of lemon sourness reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement. While the sensation may seem purely sensory, it serves vital functions in guiding food choices and protecting the body from potential harm.

Understanding the science behind sourness empowers us to use lemons more skillfully in cooking, appreciate their role in global cuisines, and consume them more safely. Whether you love that electric zing or find it challenging, there’s no denying the unique place lemons hold in both nature and the kitchen.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?