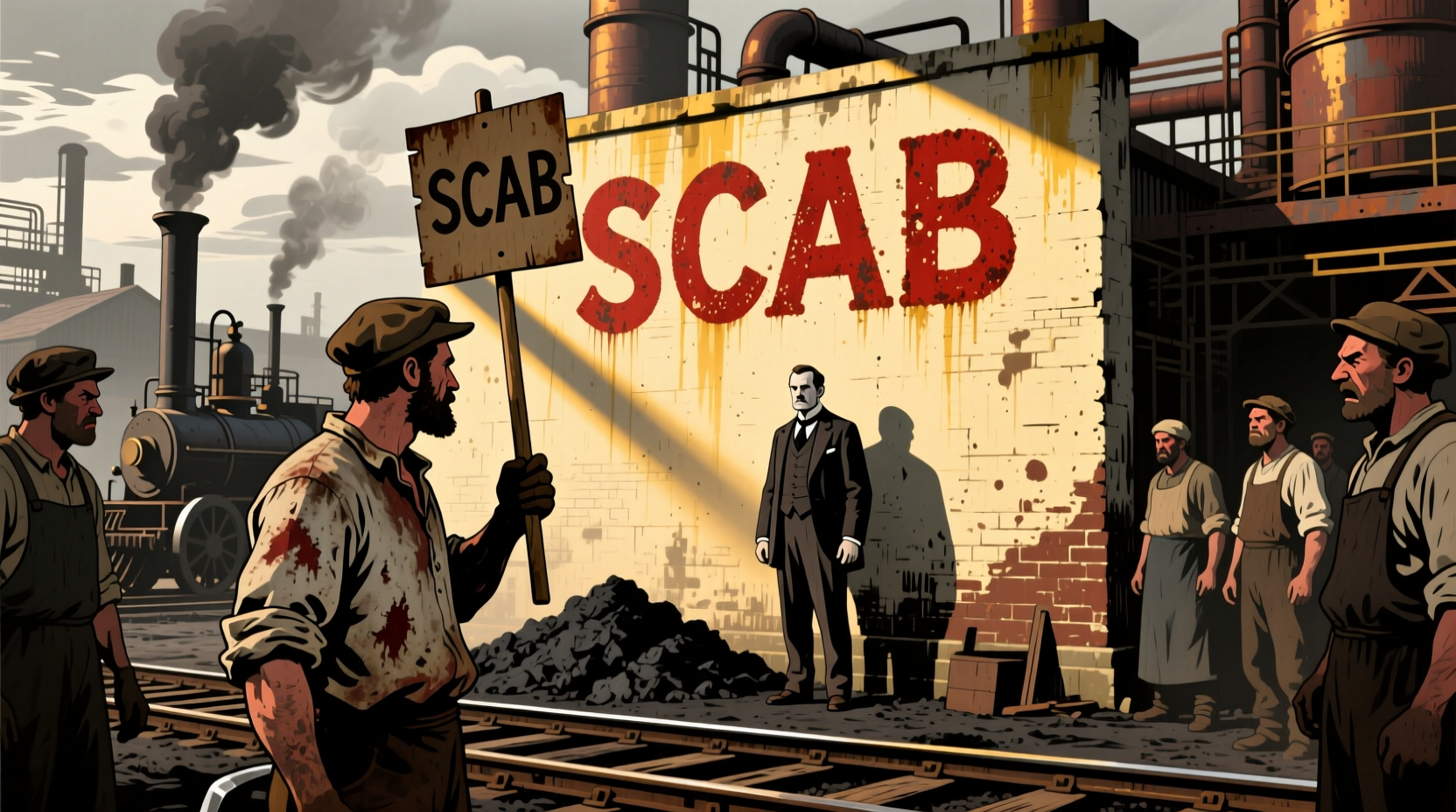

The term \"scab\" is one of the most charged words in labor history. When used to describe someone who works during a strike, it carries deep moral and emotional weight. But why do people call strikebreakers “scabs”? The answer lies in centuries of class struggle, medical metaphors, and the powerful language of solidarity. Understanding the origin and implications of this word reveals more than just etymology—it uncovers the values at the heart of collective labor action.

The Etymological Roots of “Scab”

The word “scab” predates its use in labor disputes by hundreds of years. In Old English, sceabb referred to a skin disease or crust that forms over a wound. By the 14th century, “scab” was commonly used to describe both the physical condition and, metaphorically, something contemptible or diseased. This dual usage laid the groundwork for its later application in social and economic contexts.

In early agricultural societies, calling someone a “scab” could imply they were unclean or morally corrupt. Shepherds used the term for sheep with mange, reinforcing its association with contamination. Over time, “scab” evolved into a general insult for anyone seen as violating communal norms—especially those who undermined group efforts for personal gain.

From Skin Disease to Social Betrayal

The leap from dermatology to labor politics wasn’t abrupt. By the 18th and 19th centuries, British workers began using “scab” to describe fellow laborers who refused to join strikes or who took jobs during industrial actions. The metaphor was clear: just as a scab forms over a wound but can delay healing if infected, a worker who breaks a strike might appear to “heal” production—but at the cost of long-term worker unity and health.

“Calling a strikebreaker a ‘scab’ isn’t just an insult—it’s a diagnosis of moral infection within the workforce.” — Dr. Helen Marrow, Labor Historian, University of Manchester

Historical Use in Labor Movements

The industrial revolution intensified labor conflicts, and with them, the language of resistance. In both the UK and the United States, trade unions adopted strong rhetoric to defend collective action. “Scab” became a central part of that vocabulary.

One of the earliest documented uses of “scab” in a labor context appeared in British mining communities in the 1770s. Miners on strike would label those continuing to work as “scabs,” accusing them of betraying their comrades and weakening demands for fair wages and safer conditions. The term spread rapidly across industries—from textiles to railroads—as unionization grew.

In the U.S., the Pullman Strike of 1894 marked a turning point. When railroad workers walked off the job, company-hired replacements were widely denounced as scabs. Newspapers sympathetic to labor described them as “men who crawl through the cracks of justice,” while union leaders framed their presence as a direct assault on worker dignity.

The Moral Logic Behind the Label

Critics often argue that calling strikebreakers “scabs” is unnecessarily hostile. However, within the framework of union ethics, the term serves a specific purpose: it reinforces the principle of solidarity. Unions operate on the idea that strength comes from unity. When one worker crosses a picket line, the collective bargaining power diminishes.

Labor organizers argue that strikebreakers—whether aware of it or not—enable employers to ignore legitimate grievances. In this view, accepting a replacement job during a strike isn’t neutral; it actively undermines the strikers’ ability to negotiate. Hence, “scab” functions not merely as a slur, but as a label of complicity.

This moral dimension explains why the term persists despite controversy. For many workers, allowing scabs is akin to allowing a backstabber into a team—someone whose actions jeopardize everyone else’s well-being for short-term personal benefit.

Counterarguments and Nuances

It’s important to recognize that not all individuals who work during strikes do so out of malice. Some may be unaware of the labor dispute. Others may feel economically compelled to accept any available work, especially in low-income communities. Calling such individuals “scabs” can seem harsh or unjust.

Still, unions maintain that awareness doesn’t erase impact. From a strategic standpoint, the effect remains the same: the strike loses leverage. The debate continues over whether intent should mitigate the label, but historically, the term has been applied broadly to anyone performing struck work.

A Timeline of Key Moments in the Term’s Evolution

- 1300s: “Scab” enters Middle English as a term for skin lesions and parasitic animals.

- 1770s: British miners begin using “scab” to describe workers who refuse to strike.

- 1830s: The term spreads to textile and dockworker unions in northern England.

- 1894: During the Pullman Strike, U.S. newspapers report widespread use of “scab” by striking rail workers.

- 1935: The Wagner Act strengthens union rights in the U.S., increasing public discourse around strikebreaking.

- 1984–85: The UK miners’ strike reignites the use of “scab,” with intense social stigma against those who continued working.

- 2020s: Gig economy strikes revive debates over what constitutes a “scab” in non-traditional labor settings.

Modern Usage and Controversy

Today, “scab” remains a potent word in labor activism. It appears in protest chants, union flyers, and online forums. Yet its use also draws criticism from legal scholars and media commentators who argue it fosters division and hostility.

In some countries, including Canada and parts of Europe, laws protect the right to cross picket lines, complicating the ethical landscape. Employers may legally hire temporary workers during strikes, which unions still denounce as scab labor—even when no individual malice is intended.

The rise of gig economy platforms adds new complexity. When app-based delivery drivers continue working during organized walkouts, are they scabs? Some labor advocates say yes; others argue the lack of formal employment relationships changes the dynamic.

| Context | Is “Scab” Commonly Used? | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Union Strikes | Yes | Strong culture of solidarity; replacement workers directly weaken bargaining power. |

| Gig Economy Actions | Debated | Workers are independent contractors; collective identity is weaker. |

| Public Sector Strikes | Yes | High visibility; moral arguments about public service duty intensify labeling. |

| Non-Union Workplaces | Rare | No established collective framework to define betrayal. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is calling someone a scab illegal?

No, calling a strikebreaker a “scab” is protected under free speech laws in most democratic countries. However, threats or harassment related to the term may cross legal boundaries.

Can a worker be fired for being called a scab?

Not directly. The term itself is an opinion or label, not grounds for termination. However, workplace tensions arising from strikes can lead to indirect consequences, depending on company policy and local labor laws.

Are there alternatives to the word “scab”?

Yes. Neutral terms include “strikebreaker,” “replacement worker,” or “non-striking employee.” These are often preferred in journalistic or legal contexts to avoid bias.

Mini Case Study: The 1984 UK Miners’ Strike

The year-long miners’ strike in Britain offers one of the clearest examples of how the term “scab” shaped real-world dynamics. When Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government moved to close unprofitable coal pits, the National Union of Mineworkers called a national strike. Those who continued working were branded scabs by their communities.

In villages across Yorkshire and South Wales, families severed ties with relatives who crossed picket lines. Some scabs received death threats; others were shunned for decades. Sociologists later noted that the stigma functioned as a form of social enforcement—preserving group cohesion at great personal cost.

The strike ultimately failed, but the legacy of the word “scab” endured. Even today, former miners recall the term with visceral emotion, underscoring its lasting psychological and cultural impact.

Conclusion: Language as a Tool of Solidarity

The word “scab” is far more than an insult. It is a linguistic artifact of labor’s long fight for dignity, fairness, and collective power. Its origins in disease and decay reflect a worldview in which betrayal—especially during struggle—is seen as a kind of social infection.

While its use remains controversial, understanding why strikebreakers are called scabs offers insight into the moral economy of work. It reminds us that labor is not just transactional; it is relational. Words matter because they carry the weight of shared experience, sacrifice, and solidarity.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?