Mosquito bites are a common annoyance during warm months, but for many people, they’re more than just itchy nuisances. Some experience bites that swell dramatically, become red and painful, or even mimic infections. Understanding why mosquito bites get bigger involves diving into the human immune response, individual sensitivity, and environmental factors. This article breaks down the science behind bite reactions, identifies who is most at risk, and provides practical strategies to minimize discomfort and prevent complications.

The Biology Behind Mosquito Bites

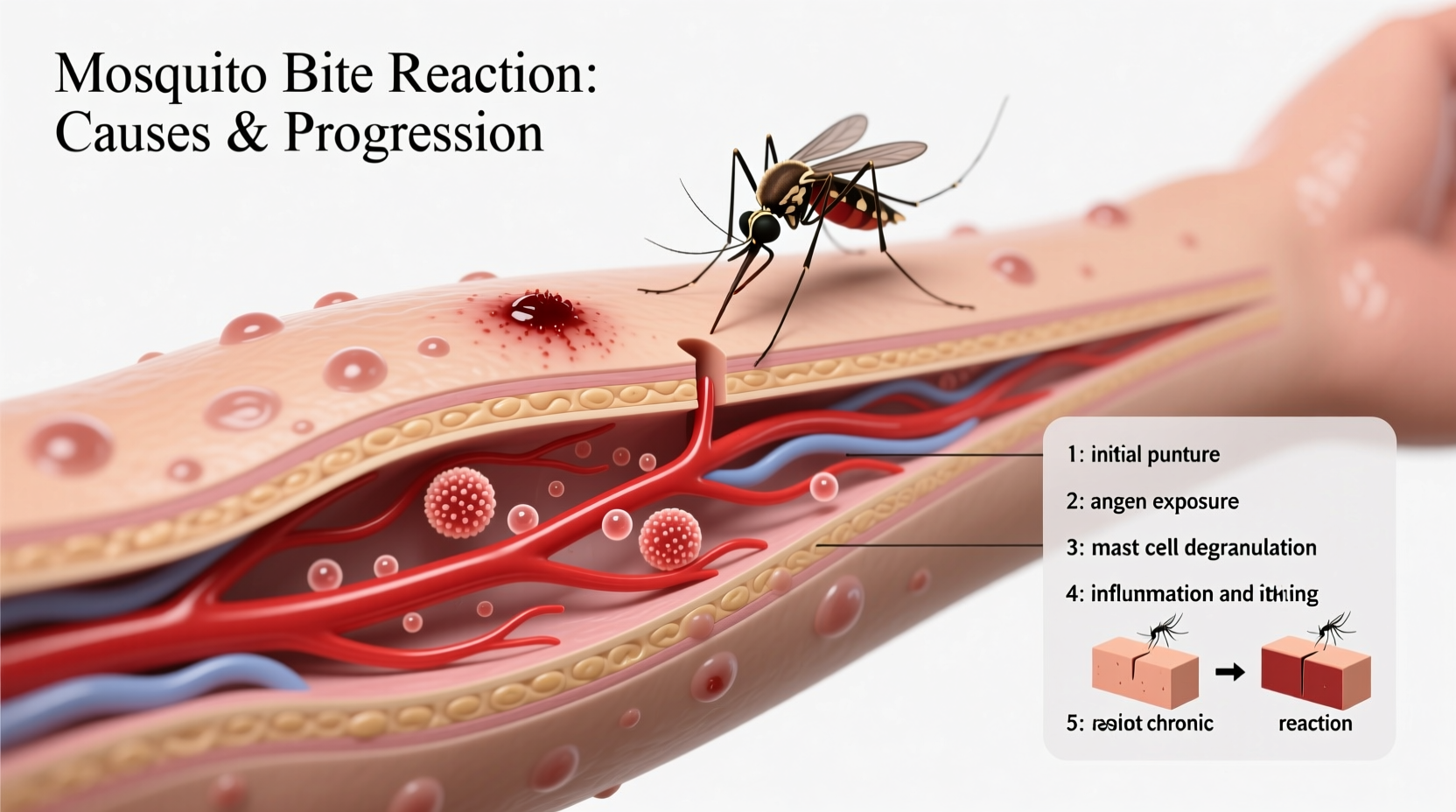

When a female mosquito bites, she pierces the skin with her proboscis to locate a blood vessel. As she feeds, she injects saliva containing proteins that prevent blood from clotting. These proteins are foreign substances to the human body, triggering an immune response. The body recognizes these proteins as invaders and releases histamine to combat them. Histamine increases blood flow and white blood cell activity in the area, leading to swelling, redness, and itching—the classic signs of a mosquito bite.

For most people, this reaction is mild and resolves within a few hours to days. However, repeated exposure can alter how the body responds. Children or individuals encountering mosquitoes for the first time may have little or no reaction initially. Over time, as their immune systems become sensitized, bites may provoke increasingly noticeable inflammation.

Why Some Bites Get Bigger: Factors Influencing Reaction Size

Not all mosquito bites are created equal. Several factors determine whether a bite remains small or balloons into a large, uncomfortable welt:

- Immune Sensitivity: People with overactive immune systems may mount a stronger histamine response, causing larger swellings.

- Age: Children and teenagers often react more intensely than adults, though some adults develop heightened sensitivity later in life.

- Bite Location: Areas with thinner skin or higher blood flow (like ankles, wrists, or face) may swell more noticeably.

- Number of Bites: Multiple bites in one area can compound inflammation, making the region appear significantly swollen.

- Species of Mosquito: Different species inject varying amounts and types of saliva, affecting the severity of the reaction.

“Some individuals develop ‘skeeter syndrome,’ a pronounced allergic reaction to mosquito saliva that can cause swelling, fever, and blistering.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Allergy and Immunology Specialist

Skeeter Syndrome: When Reactions Go Beyond Normal

Skeeter syndrome is not a true infection but an exaggerated immune response to mosquito saliva. It typically affects children, outdoor workers, or travelers visiting regions with unfamiliar mosquito species. Symptoms include:

- Large areas of swelling (sometimes several inches in diameter)

- Intense redness and heat around the bite

- Pain or warmth at the site

- Fever or fatigue in severe cases

- Blisters or bruising

These symptoms can appear within hours of the bite and last up to a week. Because the swelling can resemble cellulitis—a bacterial skin infection—it’s often misdiagnosed. Unlike infections, skeeter syndrome usually improves with anti-inflammatory treatment and doesn’t require antibiotics unless secondary infection occurs from scratching.

| Feature | Skeeter Syndrome | Cellulitis (Infection) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Within hours of bite | Gradual, often days after injury |

| Fever | Occasional, mild | Common, often high |

| Spreading Redness | Peaks early, then subsides | Progressively worsens |

| Treatment | Antihistamines, steroids | Antibiotics required |

Effective Treatment and Prevention Strategies

Whether dealing with a minor itch or a massive welt, timely intervention can reduce discomfort and speed recovery. Here’s a step-by-step approach to managing mosquito bites:

- Clean the Area: Wash with soap and water to remove residual saliva and reduce infection risk.

- Apply Cold Compress: Use an ice pack wrapped in cloth for 10–15 minutes to reduce swelling and numb itching.

- Use Topical Treatments: Calamine lotion or hydrocortisone cream helps soothe irritation and suppress inflammation.

- Take Oral Antihistamines: Non-drowsy options like loratadine (Claritin) or cetirizine (Zyrtec) reduce histamine-driven swelling.

- Monitor for Infection: Watch for increasing pain, pus, or red streaks—signs requiring medical attention.

Prevention Checklist

- ✅ Use EPA-registered repellents (DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus)

- ✅ Wear long sleeves and pants during dawn and dusk

- ✅ Install or repair window and door screens

- ✅ Eliminate standing water around your home (birdbaths, buckets, gutters)

- ✅ Consider permethrin-treated clothing for extended outdoor exposure

Real-Life Scenario: A Hiker’s Unexpected Reaction

Mark, a 28-year-old hiker, spent a weekend camping in the Florida Everglades. By the second day, he noticed his ankles were covered in bites. Within hours, some swelled to the size of golf balls, became hot to the touch, and made walking difficult. He assumed he had an infection and visited urgent care. After examination, the doctor diagnosed skeeter syndrome, noting the symmetrical pattern of bites and absence of pus or systemic illness. Mark was prescribed a short course of oral antihistamines and a low-dose steroid cream. His symptoms improved within 48 hours. The experience prompted him to adopt better preventive measures, including wearing permethrin-treated clothing and using stronger repellent on future trips.

This case highlights how easily a normal bite can escalate due to environment, exposure level, and individual biology. It also underscores the importance of accurate diagnosis—treating skeeter syndrome with antibiotics is ineffective and unnecessary.

FAQ: Common Questions About Mosquito Bite Reactions

Can mosquito bites get infected?

Yes, but only if the skin is broken from scratching. Signs of infection include increasing pain, yellow discharge, red streaks, or fever. If these occur, seek medical advice—antibiotics may be needed.

Are some people more attractive to mosquitoes?

Research shows that mosquitoes are drawn to carbon dioxide, body heat, lactic acid, and certain skin bacteria. People who exhale more CO₂ (like pregnant women), sweat heavily, or have specific genetic traits may get bitten more frequently.

Do mosquito bite patches or vitamins really work?

There’s limited evidence supporting vitamin B1 or electronic repellent patches. Most dermatologists recommend proven methods like DEET or picaridin instead of unverified alternatives.

Conclusion: Take Control of Your Reaction

Mosquito bites don’t have to ruin your summer. Understanding why they sometimes grow large—thanks to your immune system’s response to foreign proteins—empowers you to respond wisely. Whether you're prone to mild itching or dramatic swelling, the right combination of prevention, prompt care, and awareness can make a significant difference. Don’t wait for a severe reaction to take action. Start using effective repellents, treat bites early, and pay attention to your body’s signals. With informed habits, you can enjoy the outdoors with far less discomfort.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?